ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN

AL RUPPERSBERG: BOOKS, INC.

Frac Limousin, France. 2001Download pdf version

|

|

|

Allen Ruppersberg: What One Loves About Life Are the Things That Fade |

|

ALLAN McCOLLUM

I would like to write you so simply, so simply, so simply. Without having anything ever catch the eye, excepting yours alone, and what is more by erasing all the traits, even the most apparent ones, the ones that mark the tone, or the belonging to a genre (the letter for example, or the post card), so that above all the language remains self-evidently secret, as if it were being invented at every step, and as if it were burning immediately, as soon as any third party would set eyes on it . . . . It is somewhat in order that we "banalize" the cipher of the unique tragedy that I prefer cards, one hundred cards or reproductions in the same envelope, rather than a single "true" letter.

— Jacques Derrida, The Post Card: |

|

In thinking about Allen Ruppersberg's work today, after following it for thirty years, I find it impossible not to be influenced by the first time I actually saw him. That was in the spring of 1969 in Los Angeles (where both of us were living at the time), at the city's premier performance of the Living Theatre's best-known production, Paradise Now.[1]

At a certain important point in the evening—the moment when all the players (and many of the audience!) tear off all their clothes—a long rope that had been fixed to the ceiling was hurled down from the balcony, with great fanfare, and the first audience member to jump (to fly!) through the air to slide down the rope was—Allen Ruppersberg. He was already one of the most well-known and admired young artists in L.A., and cheers arose from everyone in the theater, as many others rushed to follow his leap.

|

|

Of course Ruppersberg's preoccupations with narratives led him to think a lot about books. Books participate in our culture's mythologies, as well as help shape and create them. They are publicly produced but privately read (and written). They gather and save the memories of a culture, but also—perhaps more frequently—they help dictate what is forgotten. The writer can mean one thing and the reading public can find thousands of other meanings. I believe Ruppersberg feels there is something paradoxical and otherworldly about our relationships with books.

One aspect of copying The Picture of Dorian Gray was to teach myself how to write. The original premise was to conflate two forms of 'reading' and 'writing.' One involves narrative and the other is a form of 'visual' art that is read instantly. Its presence is read all at once. I'm a visual artist: I like the experience of seeing a work of art all at once . . . reading time and drawing time are balanced half and half . . . [16] But who is doing the seeing and who is doing the reading and who is doing the writing? Who is the author of this work? In a strategy similar to that of Sherrie Levine in the 1980s, when she began making photographic copies of other artists' photographs, Ruppersberg was able to convey himself through a text written by another—inviting the viewer to see the other's work through Ruppersberg's eyes, the eyes of a copyist. In this way he dramatically illustrated the conflation of viewpoints that can bear on any act of perception, mixing his own longing with the longings of Thoreau, Wilde, their readers, and his own viewers. Indeed Ruppersberg made his feelings about the reader's expressiveness even clearer when, in 1984 and 1991, he produced drawings titled Self-Portrait (as Hurd Hatfield as Dorian Gray), in which he drew portraits of the actor who played Dorian Gray in the 1945 MGM movie version of the book.

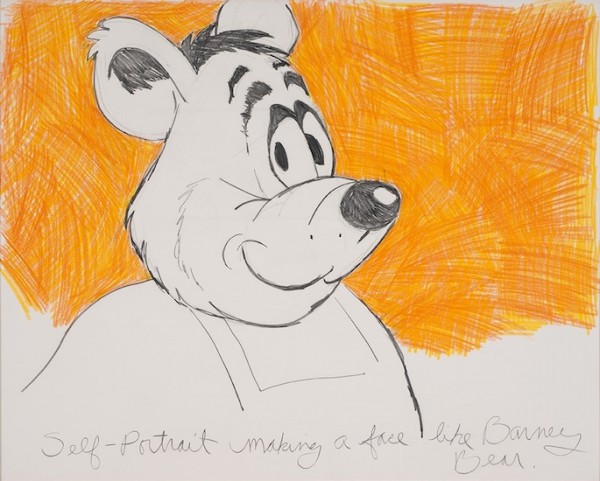

In titling his self-portrait Making a Face like Barney Bear, Ruppersberg created a paradox. The drawing was simply a hand drawing of Barney Bear. Did the title describe the artist's literal activity of "drawing" (making) a face that "looked like" the face of Barney Bear, or was he demonstrating that by "making a face" (as in crossing his eyes, or sticking out his tongue) he could imagine himself as a comic book character as easily as he could imagine himself as a specific human being named Allen Ruppersberg? He showed us not only that personal identity is a collage or collection of many different identifications—with one's parents, with local heroes in one's community, with Bugs Bunny—but also that an act of "drawing" is not only a "making" and a "seeing" but also a "being made" and a "being seen." Again, Ruppersberg repeatedly reminds us that we all remain, as social beings, collections.

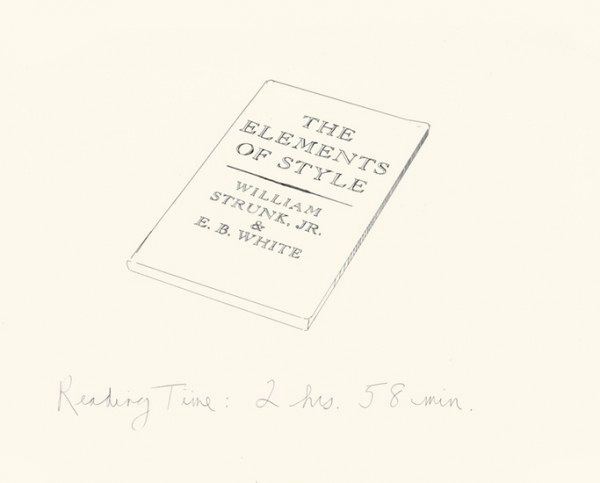

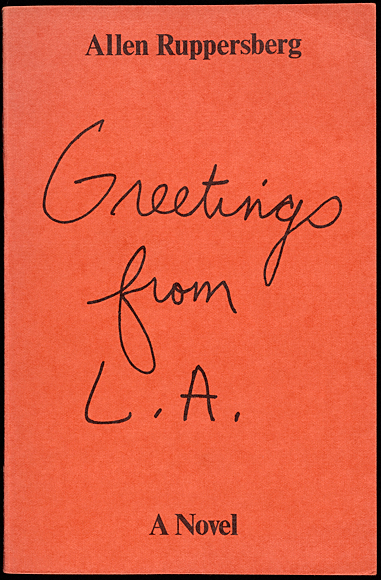

A COLLECTION OF SHEETS OF PAPER OR OTHER SUBSTANCE, BLANK, WRITTEN OR PRINTED, FASTENED TOGETHER AS TO FORM A MATERIAL WHOLE.[18] In 1956, the famous American cartoonist Jules Feiffer depicted in ten frames a nine-year-old schoolboy delivering a scholarly critique of a children's book. This bespectacled child begins by describing the book's publisher, the number of its pages, and so on, then proceeds to comments on its content—the book concerns "fist fights" and "bandits," and "lots of bad guys get killed"— and to a churlish response to what he calls the book's "love stuff," which he critiques as "a docile surrender to popular taste!" In the final frames of the cartoon, the child finally recommends the book because "the pages come out easily, so you can have a lot of fun around the house." [19] As in this child's critique, a book can be described in many ways, and can play many different roles. Books tell stories, entertain, educate, win prizes, have weight and mass, and change history. They can be bought, sold, collected, mythologized. In 1971, in addition to making visual narratives and to producing his own books, Ruppersberg began to make images of books—books he had read, books he might write, books others might have read, books on shelves, books in stacks, books floating in pictorial fields, archival manuscripts of books, letters by well-known writers of books, and so on.

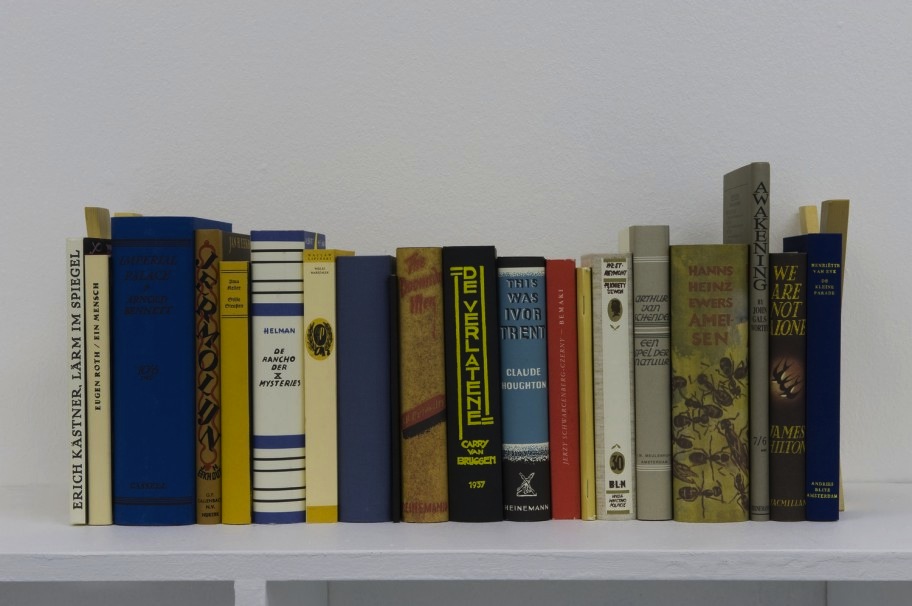

Like Feiffer's schoolboy, Ruppersberg could also look at a book with a queerly prosaic eye. In 1973 he began a series of drawings of books called "Reading Time," with each drawing including a single handwritten caption stating how long it might take to actually read the book in question. . . . A BOOK IS MORE THAN A VERBAL STRUCTURE, OR A SERIES OF VERBAL STRUCTURES; A BOOK IS THE DIALOGUE WITH THE READER, AND THE PECULIAR ACCENT IT IMPOSES UPON HIS VOICE, AND THE CHANGING AND DURABLE IMAGES IT LEAVES IN HIS MEMORY. THAT DIALOGUE IS INFINITE. . . . A BOOK IS NOT AN ISOLATED BEING: IT IS A NARRATIVE, AN AXIS OF INNUMERABLE NARRATIVES[20] Using "books" to represent the mythologies and beliefs that define the culture that values them, Ruppersberg sometimes seems to imagine that we are our books—as if we all become books, since our identities and our memories are constructed as mixtures of organized fictions and truths, all in the form of a collection of narratives. I believe it is with this perception that Ruppersberg has often represented "collections" of books—as drawings, photographs, objects, or actual collections of books he himself has printed—as if to present a kind of picture of a consciousness in and of itself. In his 1977 sequence of pencil drawings The Meditation, for instance, he depicts a toppled stack of books, running like dominoes from left to right along five long horizontal panels; by reading the books' titles the viewer gets a portraitlike sense of the person who might read or acquire (or draw) them. Yet running above the line of toppled books, another, unrelated (?) narrative—incompletely decipherable due to the overlappings of the drawings—is provided by a handwritten collection of a notes (perhaps written by the collector of the books) that appear to tell an entirely different story from the books themselves, re-creating the uneasy slippage between reader and writer (or between language and meaning) that Ruppersberg similarly depicted in To Tell the Truth. Since the late '60s and early '70s, it seems clear, Ruppersberg has been creating his own self-portrait—as well as a portrait of his age—as he depicts his collections of the narratives we carry and are carried by. WHEN YOU VISIT A NEW PLACE FOR A WEEK YOU COME HOME AND WRITE A BOOK. WHEN YOU VISIT FOR A MONTH YOU COME HOME AND WRITE AN ARTICLE. WHEN YOU VISIT FOR A YEAR YOU COME HOME AND HAVE NOTHING TO SAY.[21] In 1980, with his project André Breton, Ponce de León and the Fountain of Youth, Ruppersberg went way beyond the mythologies and narratives of his personal experience, so evident in his earlier work, and turned to mythologies and narratives of a cultural geography with which he was less familiar. During a ten-week visiting-artist appointment in Leon County, in the panhandle region of Florida, he began to explore the history and mythology surrounding the journey of the famous Spanish explorer Ponce de León on a quest for a fountain of youth. Somewhat as he had in his earlier exploration of Los Angeles mythology—done while he himself lived and worked in Los Angeles—Ruppersberg approached the legends of Ponce de León as if they formed a Surrealist continuum with all of history, where dreams of eternal youth guide all imaginings. When the project was first shown, at the Clocktower, New York, in 1981, its centerpiece was a large (seventy-two inches diameter) motorized model of a zoetrope, a nineteenth-century parlor curio that made it possible, before the invention of cinema, to view a form of animation through the use of a sequence of still photographs or drawings. The drawings visible through the windows of Ruppersberg's zoetrope formed an animated picture of the fountain of youth as León might obsessively have imagined it: a natural bubbling geyser spurting youth-giving water (looking strangely like an ejaculation of spermatozoa), repeating itself indefinitely as long as the zoetrope continued to spin. [22] Ruppersberg recognizes that myth and story are not shared only through speech or writing, but also through the creation and exchange of ideas, pictures, objects, and the enactment of rituals that determine the meanings of the myths. While a story might seem located in a specific book, it is also located within the system of a shared, cumulative culture that embraces the story that gives it its legitimacy, its value, and its force. The themes Ruppersberg developed in the late 1960s and 1970s continued in force during the 1980s, when he mined the vocabularies of public languages and popular media in new ways, exploring the narrative form as it reproduces itself through all forms of everyday human activity. He also developed many works on the themes of life and death, a preoccupation that became more and more evident with the increasingly frequent appearance of the topic of mourning. In the early 1990s, his work made another leap: he began to think about the consumers of culture's representations as well as about the representations themselves; he began to worry about the differences between personal experience of events and public, "official" descriptions of them; and, interestingly, he began to study war.

WE KEPT THE DEAD ALIVE WITH STORIES.[23] The place of the story in the space of events is poignantly explored in Ruppersberg's 1993 public memorial Siste Viator (Stop Traveler), a project for the Dutch city of Arnhem, revisiting the tragic World War II battle in the area that claimed the lives of eight thousand soldiers in nine days of September 1944. The project consisted of republishing twenty popular books of the time, five from the best-seller list of each of the four countries most involved in the battle: Britain, the Netherlands, Poland, and Germany. It was Ruppersberg's hope to represent some part of the interior lives of the soldiers who fell. I doubt if anyone could portray his intention more beautifully than he himself did in his proposal for the project:

" This work is a collection of narratives. It is about the telling of stories both fact and fiction. A memorial to individual memories and the reading of books of the private imagination combined with the public, political history. A link is established between the private experience and public memory. As this era of World War II recedes from the realm of immediate experience, I propose to create in the public mind a new personal memory that is not just another replaceable image. Dignity in a memorial is usually associated with stone and statue, with pose and gesture and with the body. I propose a similar attitude with words, as was once done with an epitaph. A comparison of words, a collision of worlds, nationalities, ideas, ideals, and kinds of literature. This work then is a reconstruction and an exhibition of history in free association to create a continuity between various narrative acts which give shape to the random acts of history." [24] All through his life as an artist, Ruppersberg has pictured the way our relationships with popular media create internal meaning within each of us, a process as profoundly personal as any more ostensibly private experience. He felt that the popular fictions read by the soldiers in the battle of Arnhem were just as much a part of the "things they carried"[25] as their equipment, their uniforms, their training, their fears, and their other motives and memories. While the fictions survived, each soldier's death took with it an individual and personal relationship with these popular stories—a loss of a memory as unique as any memory of home, family, friend, or event.

Ruppersberg dramatized this view by creating a unique war memorial through the use of printed memorabilia. In a romantic nineteenth-century cemetery near the outskirts of Arnhem, he set a prewar wooden workman's trailer of a kind common in Holland; here he displayed the republished books. The effect was of a little bookstore, though a closed one—the trailer was locked, but passersby could view the display through the windows. The books inside were organized in retail racks and stacked on tables; in addition there were World War II memorabilia referencing the battle of Arnhem, some old books on the topic, and even a poster from A Bridge Too Far, a Hollywood movie, from 1977, about the battle. Ruppersberg also made use of a second site, a prominent bookstore in the center of town, where the republished books were displayed in large stacks—the style of today's bookstores—and offered for sale. In this memorial project, a collection of retired popular narratives was made anew, and something of the inaccessible and forgotten interior worlds of the lost soldiers was recollected and shared in a new way. Siste Viator (Stop Traveler) offered a vivid representation of the grief one feels when one remembers that the memories of the dead—even their shared memories of common cultural narratives—can never be recovered.

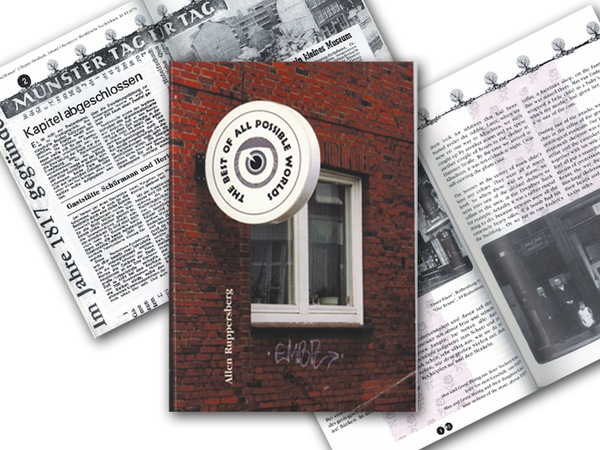

The locations selected for the tour come from the memories of the citizens themselves and become a way to look past the stone facades and take individual experiences into account. The tour becomes a search for memories in the first person in a city that was virtually destroyed by World War II. What are the consoling memories with which people live? How many memories are rooted in historical event? The tour spirals out of the museum to the private space of the personal memory.[27] For the occasion Ruppersberg wrote and published a book (what else?), a "Tourguide" containing a text about the project, maps and photos of eleven local sites, and eleven stories of personal reminiscence written by local citizens from all sections of the community who lived or had lived nearby. These stories were specifically written for the project by people who were interested in participating, and Ruppersberg selected for the tour certain sites described in their stories. The eleven sites were physically marked by large, circular, vacuformed plastic signs, to help "our hero, the viewer"[28] locate them.

When an artist dedicates his life to honoring memory, and "the things that fade,"[29] a deep poignancy can begin to develop when his work itself grows distant in one's own memory. As I was taking Al's Münster tour, having followed his work for so many years, I became aware of a faint feeling that between the 1969 Al's Cafe and the 1997 The Best of All Possible Worlds, a full circle was somehow being drawn. In Al's Cafe, a fictitious social space and a real social space were consolidated into an event that lived just long enough to plant seeds of meaning in a selection of everyday objects—leaves, wads of paper, bubble gum, photographs. Common, public things were consumed and transmuted into things of special and private meaning, repositories for future memories of the event itself. "A thing can be domesticated by man even if it rolls out of the factory on the most impersonal and technologically advanced conveyers, since it nonetheless ends up in someone's house, where a person assimilates it into his private way of life, endowing it with numerous general, practical, conscious and unconscious meanings," Mikhail Epstein has written. Thus the brief and short-lived Cafe was—like nearly all of Ruppersberg's work—a love letter to the ephemeral and to memory, a valorization of the things that are destined to disappear.

MARIA SCHÜRMANN, KLEMENSTRASSE FASSADE GALERIA-KAUFHOF This is not a fictional story, this is a tragic and true story. It does not resonate well with the "cultivation of one's garden" that Voltaire seems to advise in Candide; in fact it sounds rather like one of the fictional nightmares he describes in the miserable world outside Westphalia. In his introduction to the "Tourguide," Ruppersberg writes, "In a city which is continually referred to by its residents in an air of cheerful pride, as if everything, they feel, has gone well, and where there are an abundance of beautiful historical landmarks to confirm this, I thought it a good opportunity to introduce Voltaire's fictional world, the best of all possible worlds, to the historical reality of Münster."[33] Quoting from Voltaire's book, he recounts the question of the story's old woman who, referring to the tortures of Candide's travels, asks him,

"I would be glad to know which is worst, to be ravished a hundred times by Negro pirates, to have one buttock cut off, to run the gauntlet among the Bulgarians, to be whipped and hanged at an auto-da-fe, to be dissected, to be chained to an oar in a galley; and, in short, to experience all the miseries through which every one of us hath passed, or to remain here doing nothing?" In this single operatic work, Ruppersberg has painted the dilemmas of art and urban life with a brush so broad and thorough that it is able to take into account popular beliefs and fictions of the eighteenth century forward through the unspeakable horrors of World War II and on into the era of today's often mawkish and sterile global tourism. He dramatizes the disappearance of personal histories and suggests their possible recovery through an art which recognizes that it has as much potential for damaging the truth as for protecting it; and he shapes a possible way to repair some of the damages done in the past. In all of Ruppersberg's recent public work, a new model for making history is developing, as well as a new role for the artist: where a monopolistic public view begins to erode the common truths of the everyday, the artist can be instrumental in restoring the balance; and if we and our civilization evolve like a vast, ever-growing, labyrinthine collection of books and stories, it is a collection that an artist can always learn to arrange more beautifully. Notes: [1.] This particular production of Paradise Now, Directed by Julian Beck and Judith Molina, was staged at The Bovard Auditorium, University of Southern California. [2.] The truth is I have loved Al's work for more than thirty years. It is a part of my life and memory, and I tend to be a bit sentimental about it. More than that, I have been deeply influenced by it both personally and professionally—not only in my youth, but during all the time between then and now, and even at this very moment. And while we are virtually the same age, I have always regarded him as a mentor, light-years ahead of me in thought and practice, and I have always felt privileged when he has had the time to share a visit. I can, after all these years, with all lucidity imagine that this will be the case for another thirty years. [3.] Ruppersberg, Allen. From the "Menu" at Al's Cafe, 1969. [Other Al's Cafes: here] [4.] Peter Coyote, interviewed by Etan Ben-Ami, Mill Valley, California, January 12, 1989. Found in The Digger Oral History Project at http://www.diggers.org/oralhistory/peter_interview.html. The full quote reads, "With the clarity of one's early twenties, I decided that theater was no longer an adequate vehicle for change, because the fact of paying at the door told you that it was a business. When you bought a ticket, you knew in your deepest culturally resonant center that this was a business and that while you may not like the message of the play, you knew that it was just like going into a store and not liking the merchandise. You turn around and you walk out. You're not questioning 'store-ness.' We wanted to question 'store-ness': What is the nature of business? You can't do that from within a business. So from that perspective, Free was simply the appropriate, efficacious tool for the kind of investigations that were going on. When it wasn't a business and people were doing something just because they felt like it, it threw the whole subject of coercion into the light. It forced you to take responsibility for being coerced or remaining coerced if you didn't like what you were doing." [5.] Ruppersberg, "Fifty Helpful Hints on the Art of the Everyday," in The Secret of Life and Death, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, and Santa Barbara: Black Sparrow Press, 1985), pp. 11-14. All unattributed quotations used as section headings in the present essay are from this text. [6.] Mikhail Epstein, After the Future: The Paradoxes of Postmodernism and Contemporary Russian Culture, trans. Anesa Miller-Pogacar (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1995). [7.] 23 Pieces (1968), 24 Pieces (1970), and 25 Pieces (1971). [8.] . It's difficult for me to think back to these early works of Al's without being reminded of Sophie Calle's beautiful and poignant 1983 series L'Hôtel, in which she took a job for a few days as a chambermaid in a Venetian hotel and secretly photographed the possessions of guests while they were absent from their rooms. The photographs, while ostensibly taken in an attempt to learn truths about the objects' owners, only underscored the impossibility and the loneliness of such a quest. [9.] It was easy for me to guess that some of these addresses were taken from Ruppersberg's own address book, because, to my surprise, my own address appeared there. [10.] Ruppersberg, quoted in Kristine McKenna, "Stuff Is His Middle Name," Los Angeles Times, Calendar Section, November 21, 1993. [11] For an artist to raise the money to run a seven-room hotel may sound odd; I should make clear that the hotel was not a hugely expensive project. Nearly everything was produced on a shoestring, with thrift-shop items, beds rented from Budget Furniture Rentals, Inc., and various objects from Ruppersberg's own growing collection of ephemera and memorabilia. [12.] As an example, my own experience at Al's Grand Hotel became a permanent part of my memory—not just because I slept beneath a fifteen-foot Christian cross that Al had somehow managed to stuff into the room (oddly challenging my own religious upbringing), nor simply because it was a particularly romantic evening, but also because of a personal exchange between Al and myself: he paid off a $30 loan I'd made him by giving me the room at no charge. At the time, Al often borrowed money from his friends and later appeared at their doorsteps with an artwork as repayment—his way of expressing friendship and gratitude, as well as his own particular style of entrepreneurship. [13.] This remark is made by the Lewis Stone character, who also says, "What do you do in the Grand Hotel? Eat. Sleep. Loaf around. Flirt a little. Dance a little. A hundred doors leading to one hall, and no one knows anything about the person next to them. And when you leave, someone occupies your room, lies in your bed, and that's the end." Screenplay by William A. Drake, based on the 1932 play Grand Hotel, by Vicki Baum. [14.] Paul Schroeder, Writing Places Out of History, from a draft transcript of a talk given at the American Society for Cybernetics International Workshop: "Design, Planning and Human Understanding," in Santa Cruz, California, on April 3, 1998. [15.] Jorge Luis Borges, "About William Beckford's Vathek," 1943, in Other Inquisitions, 1937-1952 (New York: Clarion/Simon & Schuster, 1964), p. 140. [16.] Ruppersberg, quoted in Daniel Levine, "Allen Ruppersberg," Journal of Contemporary Art 5, no. 2 (Fall 1992): 68-77. [17.] Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection, 1984 (reprint ed. Durham: Duke University Press, 1993), p. 151. [18.] A definition of "book" in The Oxford English Dictionary. [19.] Jules Feiffer, Sick, Sick, Sick: A Guide to Non-Confident Living (New York: McGraw Hill, 1956), pp. 42-43. [20.] Borges, "For Bernard Shaw," 1951, in Other Inquisitions, pp. 163-64. [21.] French saying. [22.] Along with the oversized zoetrope, Al also offered a series of "gift boxes," each containing a desk blotter that had been "soaked in the waters of the fountain of youth." I remember that I myself somehow became caught up in the Surrealist continuum of this story: I was visiting Al in Los Angeles while he was working on these blotters, vacationing in a camper tent we erected in his girlfriend's back yard. One day, oddly, I began thinking that true fame might be won by writing a bathroom-wall poem that the entire population would come to memorize, and I spent the afternoon trying to write such a simple, elegant scatological masterpiece—with some success, I believe. When Al came over after his working day, he told me that he'd been writing phrases and drawing pictures on his blotters, and that he'd been wracking his brain trying to remember a good bathroom-wall poem. When I confessed that I'd spent the whole afternoon trying to write one, we both marveled at the mystical confluence of our subconscious minds, and the next day he used my best poem to finish one of the blotters. [23.] Tim O'Brien, "The Lives of the Dead," in The Things They Carried (Boston: Houghton Mifflin/Seymour Lawrence, 1990), p. 267. [24.] Ruppersberg, in a brochure written to accompany his Siste Viator (Stop Traveler) project. [25.] I quote, again, O'Brien, and the title of his book The Things They Carried. [26.] Ruppersberg, "Notes and Acknowledgements," The Best of All Possible Worlds. Klauss Bussmann/Kaspar Konig/Florian Matzner, 1997), p. 7. [27.] ibid. [28.] Ruppersberg's original proposal for the project used this wonderful phrase to describe its participant visitors. [29.] My title for the present essay, "What One Loves about Life Are the Things That Fade," is taken from a Ruppersberg piece. Reading the New York Times one day, Al came across a page that was entirely black except for this phrase, printed in bold white. The page was part of an ad for the film Heaven's Gate. Al was so moved by the phrase that he cut out the entire newspaper page and framed it just as it was. The framed page was shown in an exhibition at the Christine Burgin Gallery, New York, in 1988. [30.] Epstein, After the Future. [31.] Brian Massumi, "Everywhere You Want to Be: Introduction to Fear," in Massumi, ed.,The Politics of Everyday Fear (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993). [32.] Ruppersberg, The Best of All Possible Worlds, p. 21. Look here for some very brief synopses of the other stories. [33.] ibid., p.7. [34.] ibid. Return to: Texts on other artists Return to Other Texts... |

Edward Kienholz, Barney's Beanery,1965

Edward Kienholz, Barney's Beanery,1965

All cities, towns, neighborhoods, families, and individuals determine narratives for themselves, and are conditioned by the myths they perpetually create and re-create for themselves. Hollywood, a city of mythmakers, is certainly no different. When Ruppersberg chose to move to Los Angeles and to go to Chouinard, in 1962, he was planning to become a commercial artist, and his evolution into a fine artist in a big city was a period of great change for him. He later described his arrival like this: "L.A. was like a dream come true for a Midwestern boy—it was the land of dreams then. It was the best."

All cities, towns, neighborhoods, families, and individuals determine narratives for themselves, and are conditioned by the myths they perpetually create and re-create for themselves. Hollywood, a city of mythmakers, is certainly no different. When Ruppersberg chose to move to Los Angeles and to go to Chouinard, in 1962, he was planning to become a commercial artist, and his evolution into a fine artist in a big city was a period of great change for him. He later described his arrival like this: "L.A. was like a dream come true for a Midwestern boy—it was the land of dreams then. It was the best."

Allen Ruppersberg, Self-Portrait Making a Face like Barney Bear , 1974.

Allen Ruppersberg, Self-Portrait Making a Face like Barney Bear , 1974.