The Carnegie Museum of Art's Hall of Architecture boasts the third largest collection of architectural casts in the world. Cast Collecting 1

Guided by the view that a replica of a masterpiece was superior to a mediocre original, collectors from the time of Rome's first emperor until the early 20th century amassed great plaster-cast collections of recognized masterworks. As early as the fourth century BCE, the Greeks made plaster casts of famous marble statues. In Roman times, the passion for Greek sculpture resulted in the reproduction of works of art. Plaster casts were also popular during the Renaissance, when the "rebirth" of antiquity influenced artistic taste. By the late 18th century, inspired by new archaeological finds, collections of plaster casts could be found in most European cities.

Carnegie Had A Dinosaur Too 3

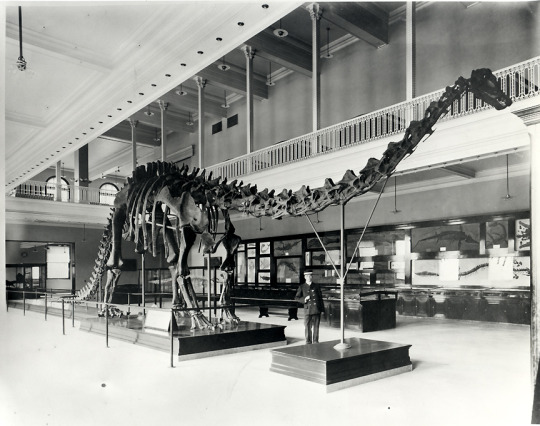

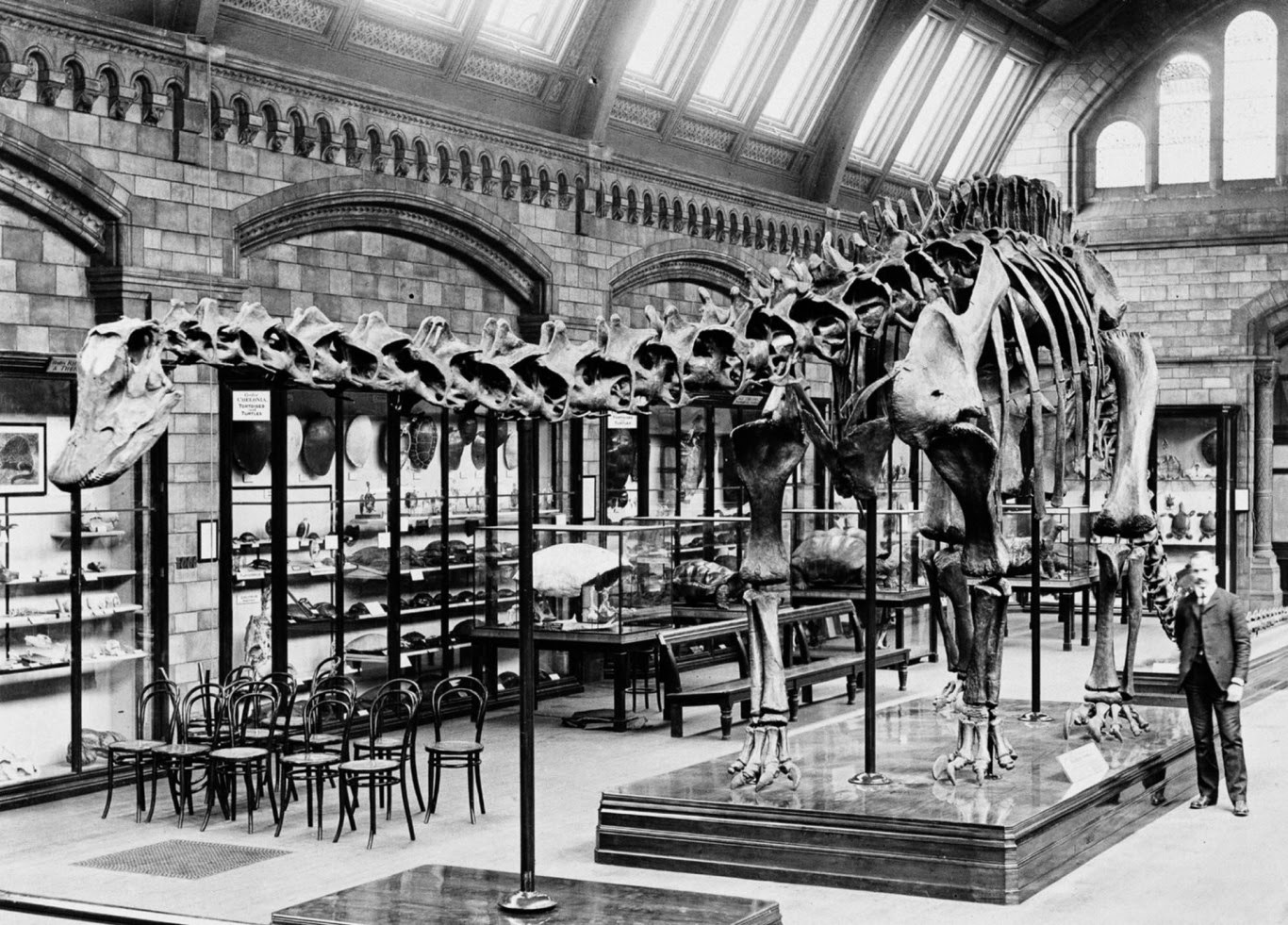

Like many Americans, Andrew Carnegie became excited when parties from the American Museum of Natural History collected the remains of large dinosaurs. Reading the New York Journal in November 1898, Carnegie came upon a headline—MOST COLOSSAL ANIMAL EVER ON EARTH JUST FOUND OUT WEST!—accompanied by a drawing of a Brontosaurus standing on its rear legs, trying "to Peep into the Eleventh Story of the New York Life Building." Carnegie scrawled a note onto the article—"Dear Chancellor, buy this! For Pittsburgh"—and mailed it with a ten-thousand-dollar check to William J. Holland, the newly appointed director of the Carnegie Museum. The steel tycoon had become a dinosaur hunter.

Curiously, the article and the accompanying drawings were entirely based on the discovery of one bone, an eight-foot Brontosaurus (more properly called Apatosaurus) thigh specimen uncovered in Wyoming by the American Museum collector William Reed. Holland met with Reed and signed him to a year's contract with the Carnegie Museum. In return, Reed gave Holland a dinosaur bone to take back to Pittsburgh and promised to find others.

Men at work in Sheep Creek Wyoming, where the dinosaur Diplodocus carnegii was discovered

The collectors were discouraged but vowed to continue. Two months later they had worked their way thirty miles from their original site into the Sheep Creek region of Wyoming. This was geologically a part of the Morrison formation, in which important dinosaur finds had been made before. Finally, on the morning of July 4, 1899, Coggeshall discovered a dinosaur's toe bone. By afternoon the men had uncovered more bones and realized the find was significant. It was a well-preserved Diplodocus, the most complete found to that time. Because of the date of its discovery, Coggeshall joked that this Late Jurassic beast from 120 million years earlier be called the "Star-Spangled Dinosaur." Director Holland, however, describing the find in the scientific literature in 1901, chose to honor his patron, officially naming the dinosaur Diplodocus carnegii.

This was no simple task, for the Diplodocus skeleton had almost three hundred bones, with twenty-two feet of neck and fifty feet of tail. In life D. carnegii had weighed about twelve tons; although most of that weight was taken up by flesh, the bones were now petrified and were themselves extremely heavy. Arthur Coggeshall had to invent a structural steel framework to support the vertebrate column, a system still used for exhibiting dinosaurs around the world.

Because of its widespread dispersal, D. carnegii has become the best-known dinosaur in the world. It became famous enough to have at least one poem written in its honor, an old song quoted by Holland in his book To the River Plate and Back: "The Crowned heads of Europe/ All make a royal fuss/ Over Uncle Andy/ and his old Diplodocus."

The Carnegie Museum of Art's Hall of Sculpture 5

The Hall of Sculpture was originally designed to house Carnegie Museum of Art's collection of reproduction Egyptian, Near Eastern, Greek, and Roman sculptures. When the hall opened in 1907, a majority of these 69 plaster casts occupied the ground floor. The design of the hall was inspired the Parthenon, the fifth-century BCE temple in Athens, Greece. Dedicated to the virgin goddess Athena, the protectress of Athens, the Parthenon (from the Greek word parthenos, meaning "maiden" or "virgin") was built overlooking the city. The imperial scale of the Parthenon, the beauty of its decorative sculpture, and the visual harmony among its architectural elements account for its renown ever since it was built.

The architects of the Hall of Sculpture chose to model their room on the Parthenon's cella, or inner sanctuary, which was distinguished by a double tier of columns (the cella of the Parthenon had to accommodate a 40-foot statue of Athena). The hall was constructed with brilliant white marble from the same quarries in Greece that provided the stone for the Parthenon. Because the Hall of Sculpture was a public museum space, the architects created a balcony with a decorative iron railing to make viewing from the second floor possible. The balcony of the Hall of Sculpture is now reserved for decorative arts objects--principally glass, ceramics, and metalwork--that may range in date from the 18th to the 20th century. While much of Andrew Carnegie's cast collection, including several notable examples from the Parthenon itself, is currently on view in the museum's Hall of Architecture, several works have been placed on pedestals around the Hall of Sculpture balcony as reminders of the original purpose of the room. Still installed directly below the skylight in the position it has occupied since 1907 is a plaster reproduction of the carved frieze, or decorative band, that was originally positioned on the exterior of the Parthenon's cella. This frieze depicts the procession that inaugurated the annual festival of Athena in ancient Athens. Today in the Hall of Sculpture, Carnegie Museum of Art displays works from its permanent collection; it has frequently been used for site-specific installations and performances. For the 1988 Carnegie International, the museum's triennial exhibition of contemporary art, the German artist Lothar Baumgarten (b. 1944) produced The Tongue of the Cherokee for the hall's skylight ceiling. This work presents the Cherokee alphabet, which was formulated in the early 19th century. Just as the choice of a Greek-inspired design for the Hall of Sculpture reflects the importance of that ancient culture to American politics, so the Cherokee alphabet serves as a reminder of the presence in this country of Native Americans and recognizes their role in American history. 6

Exploring the Question of 'What-is-Contemporary?' 7

In describing her thinking for the 57th Carnegie International, Carnegie Museum of Art curator Ingrid Schaffner seeks the answer to the question, 'What is Contemporary?' :

If the surrogate pieces seem archaeological, representing cultural artifacts as if they were the unreadable relics of a past generation, McCollum's more recent work has moved into the realm of paleontology and natural history. These copies or surrogates are not of artificial objects, but of what McCollum calls "copies produced by nature." 10 In The Dog from Pompei (series begun 1990) and Lost Objects (series begun 1991), McCollum simply inserts himself into the process of reproduction or replication inherent in the natural formation of fossils. The dog is an indefinitely reproducible series of polymer-enhanced Hydrocal casts, taken from a mold that was made from a cast based on a "natural mold" left by the body of a dog that was smothered in the Vesuvius explosion of 79 A.D. The Lost Objects "are cast in glass-fiber-reinforced concrete from rubber molds taken of fossil dinosaur bones in the vertebrate paleontology section of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh." Fifteen different molds have been painted in fifty different colors, making "750 unique Lost Objects to date."

Traditional notions of the relation of copy and original, not to mention the status of the artistic "authorial" function, are clearly under considerable pressure in these works, and their effect is very difficult to pin down. In some ways, these works seem to fulfill Walter Benjamin's prediction that the age of mechanical reproduction would mean that the endless series of identical replicas would replace the unique art object with its "aura" of authorial expressiveness and tradition. McCollum makes "mass produced" objects in a kind of art factory, like an automobile manufacturer. Yet the objects do seem to have a kind of melancholy aura, one that is increased rather than diminished by their mass gathering in the space of display. It is as if they were occasions for a double mourning, first for the deaths of the remote creatures whose traces are retraced here, and second for loss of auratic uniqueness itself, as if we were grieving over the loss of the ability to feel certain kinds of emotions. Certainly these works don't tend to provoke laughter the way the surrogates do. They are too literal in their evocation of death, disaster, and mass extinction. The dog, as the favorite domestic animal of the Romans, evokes the sphere of privacy and the everyday in the proximity of catastrophe. The bones, on the other hand, evoke the larger public spheres of the nation and the world--the dinosaur as giant "ruler of the earth," a symbol of the American nation or of the human race more generally. Taken together, McCollum's "dog and bone" series suggest a kind of symbiotic completeness in the postmodern rendering of nature.

The installation of these bones in the neoclassical atrium of the Carnegie Museum is for me (also an American) an uncanny resurrection of Thomas Jefferson's lost "bone room" in the east Room of the White House, as if we were privileged to go back in time and see the mastodon bones replaced by their cultural descendants, the dinosaurs. 11

Notes: 1. Carnegie Museum of Art Hall of Architecture: Cast Collecting 2. Ibid. 3. Sassman, Richard, "Carnegie Had A Dinosaur Too," American Heritage Magazine, March 1988, Vol. 39, Issue 2. 4. Sassman, Richard, Ibid. 5. Carnegie Museum of Art Hall of Architecture 6. Ibid. 7. Schaffner, Ingrid, "What is Contemporary?," Carnegie Magazine, Spring 2016. 8. Schaffner, Ingrid, Ibid. 9. Mitchell, W.T.J., excerpt from The Last Dinosaur Book: The Life and Times of a Cultural Icon, Chapter: "Coda: PaleoArt." University of Chicago Press, 1998. 10. Allan McCollum: Interview by Thomas Lawson, (Los Angeles: A.R.T. Press, 1996. I'm grateful to Anthony Elms for bringing McCollum's work to my attention. 11. Mitchell, W.T.J., Ibid. |