ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN:

Imperial Valley Press

September 24, 2001.

by AARON CLAVERIE Staff Writer |

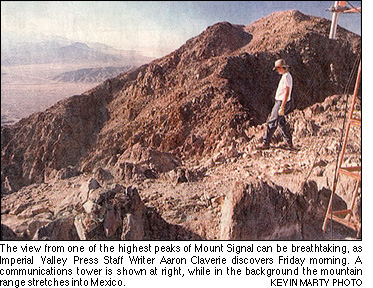

MOUNT SIGNAL—"Because it is there" seemed Iike a good enough reason at the time. After two hours scratching up Mount Signal and two hours crawling down—because it was there—it didn't seem so insightful. Mount Signal, or "El Centinela," rises 2,300 feet on the Mexican side of the border west of Calexico. It's asking to be climbed, especially on a clear morning after a rain when it seems to appear bigger and more defined. Just one bit of advice before you grab a pair of boots and some water and head for the base of the mountain. The U.S. Border Patrol requires any U.S. citizen climbing the mountain to cross back into the U.S. at an official Port of Entry after descending, instead of staggering back through the desert to your truck.When you go, make sure there is someone waiting for you on the Mexican side of the border to drive you back to Mexicali. It wouldn't hurt if that person carried a first-aid kit and some extra supplies, too. If I had a chance to do it again, that's what I would have arranged. What is it they say? Hindsight and all? Staff Photographer Kevin Marty and I arrived at the base of the mountain on the U.S. side at 6 a.m. The sun hadn't yet cracked the horizon but an orange glow illuminated our way toward the border. Marty had told the Border Patrol that we were climbing the mountain. The BP didn't stop us because, as agents told us when we got back, "We don't care if you go over but we do care when you, or anyone else, comes back." We started the climb on the northern side of the mountain, which let us climb up in the cool shade of the morning. As we started up the side the rocks went from big to boulders to slippery stones and back again. Marty carried a gallon of water in his right hand and lugged a backpack full of photo gear. My water bottle was cinched around my waist with my belt. Was. About a half-hour into the climb I reached up for a handhold and the water bottle slipped. I felt it go and looked behind me. It slowed and almost stopped sliding within reach. Almost. Nano-seconds later the bottle flipped, cracked—water spouting out of the side—and crashed, thump .... thump-thump ... thump. I couldn't see Marty because he was taking a different path up but could hear him say, "I thought that was you." I wanted to tell him something clever such as, "You'd have heard a whole lot of screaming had it been me," but I was so absorbed by losing my water, I didn't say anything. I just started climbing again, focused on the rock in front of me and tried to think of something; anything besides water. For the first couple hours it was easy because climbing up the mountain was engrossing. Hanging on the side of an outcropping over a particularly sharp drop, feeling adrenaline surge when the body's center of gravity shifts and then rights itself—that's good stuff. We got to one summit and Iooked over the Valley shrouded in a morning mist. It makes you appreciate the people who turned a foreboding desert into a quilt of green and gold fields. Looking down from Mount Signal you can see the exact point where the fields stop and the desert begins. Canals shimmer. Once at the first summit we spied what we thought was the real summit where two antennas stood. So away we went. We saw a purple cactus, the only one we saw. Climbing to the second summit was somewhat easier than getting to the first. It had been marked with blue arrows and there was a trail to follow. At one point an arrow showed the way up a steep bank of rocks. "The final ascent," Marty said. By this time I was on my 16th wind but it took me a 17th to make the last push over the rocks to finally reach the summit with the antennas. Once there we walked around and checked out the scenery. There were old backpacks and solar panels up there. There was a bunch of empty water bottles. We looked at the even higher peak. After telling our story to a man who had climbed up to that peak, he shot back, "You didn't climb and see the cross? Ahhh, you went halfway." Damn. It didn't feel halfway standing up there. It felt better than that—but he is right— climbing that last peak is something to look forward to. We started back down. Marty, who is of Andorran descent or was raised by mountain goats, shot down the way we had come up. He was actually running that run where you have to keep running because if you stop you will lose your balance. I watched him motor along and felt no desire to try to keep up. Getting down is mind-numbing, potentially dangerous; physically exhausting and a damn good case for a tram. Every footfall was taken giingerly with trembling legs. I had to make sure the footing was secure because one false step could send a person head first into a crag. One seemingly true step that turned out to be false could bring about the same fate. Some of the sedimentary rocks looked sturdy but snapped under weight, shifted and slid or proved more slippery than they appeared. All the way down you can't look at the scenery because you are constantly watching the front of your boots. I heard something unintelligible ... Marty's voice. He was standing near the first summit about a half-hour away. "I found the water tower," he said. Water. That sounded good. I hasn't had any since we left at 6. It was 10 a.m. when Marty went toward the water tower. I took a different path down, following a ravine to the north. My water bottle had fallen out on this side of the ravine and I had some vague hope I was going to find it. Dried saliva caked the top of my mouth and left a gummy film on my teeth. Heat emanated off my body. I tried to catch some shade behind a random boulder but I knew I couldn't stay long. The sun was reaching its noontime apex and that meant no shade whatsoever. My mind started to wander. I focused on seeing my truck, getting to it and driving to 7-Eleven for a Big Gulp. When I wasn't thinking about that, I trudged on with a song lyric stuck in my head. "Them boys are thirsty in Atlanta but there's beer in Texarkana." Yeah, the "Smokey and the Bandit" song. I couldn't get it out my head and in my heat induced delirium I started to analyze the movie and the song. Why wasn't Coors sold in Atlanta? Was the script written as it was because the cities rhymed? Humming "eastbound and down loaded up and trucking" I saw the end. The ravine I had walked down opened to the Mexican road we had crossed to get to the base. Walking slowly toward the border, I saw Marty standing with three U.S. Border Patrol agents. In the middle of the road—a plastic gallon water bottle. There was still a swig or two left in the jug. I figured Marty had left it for me and picked up the gallon jug and walked over toward the guys. The scant amount of water merely served to loosen up the dried spittle that caked my mouth. I crossed the border and found out about the rules for crossing the border. It turns out the agents could have driven us back to the Mexicali border to walk through the Port of Entry. They didn't, though. Maybe out of pity. They told us how dangerous what we had just done was. They said there have been a bunch of bodies found in the area lately. One of the agents asked, "You were out there without water?" "I found this," I said and held up the now empty jug of Mount Everest-brand water. "Found it on the road there." "That wasn't water," the agent said. Staff Writer Aaron Claverie |

Mount Signal Poems and Stories