|

Hetzel The Photographer

When it is said that Leo Hetzel was not considered an "artistic" photographer, it is not meant to belittle his efforts. Surely, scores of Imperial Valley homes proudly displayed Hetzel's desert-in-blossom scenes (hand-colored by his wife and daughter) for years. And Hetzel's portraits were flattering to practically all who posed before him. While those professional trademarks are widely appreciated in the Valley, Hetzel should not be compared to pioneer photographic artists such as Edward Curtis or Eadweard Muybridge. Instead, Hetzel should be recognized for contributing a splendid portfolio of the unique history of Southeastern California. He should be recognized for having the presence of mind to realize that the activity around him was historically relevant: the settling of a last American frontier. And he should be recognized for recording that activity on film.

But in reflecting on his life and work, one senses he shared a fierce pride and strong work ethics with those he photographed. He was as proud as the farmer, the merchant and the field hand were in being a part of a destiny created.

Hetzel was a straight-forward documentarian, which means he photo graphed life exactly as he saw it. As a result, the observer obtains a true picture of the spirit of the time. The image rarely betrays the action. Beyond that, Hetzel obviously believed that the big picture was the truest picture. His family portraits often leaked clues of the families' conditions: in front of their modest abode or with barefoot children and the family pet parrot. Hetzel took the time and effort to set up for the better photograph. Rather than taking a quick shot of the outside facade of a Mexicali casino, he went inside and caught the true action.

The author vaguely remembers Hetzel's desert scenes hanging on living room walls and those portraits in high school yearbooks. But he learned to appreciate Hetzel's eye for social documentation while writing historical columns for the Imperial Valley Press in 1978-79. A story about Hetzel led him to the historical files in the Spencer Library/Media Center at Imperial Valley College. Most of the thousands of surviving negatives were 6 1/2 by 10 inches. A recent effort had been made to make contact prints of each of those negatives but, unfortunately, most of those prints were not sufficiently "fixed" and are fading quickly. Others had attempted to identify the people, places and events depicted in the files. But with so many negatives on file, identification is virtually impossible.

One thing is clear, however. The unique images housed in his files are probably the most accurate possible source of historical data on the Imperial Valley available. Descriptions of the plank road traversing the so-called American Sahara can't possibly be as adequate as Hetzel's photographs. And who can imagine a land-leveling operation with teams of Fresno scrapers without benefit of a photograph?

Hetzel came to El Centro in 1910 and quickly declared he was ready to settle down for good. He tempered his photographic skills while traveling aimlessly around the Pacific Northwest as a young man. Competence in studio and business management were refined later while working in a Los Angeles studio. When he established his own studio in a tin building in El Centro, he channeled his talents toward the good of the community. He was a good family man and was a noted civic leader. He even tried his hand at farming. But Hetzel will always be known as the man who took all those "old pictures." In the 30 years following his arrival, his excitement about the community growing around him never waned. Opportunities increased with each new discovery of a promising crop. Towns grew rapidly and support services strained to keep up. It was an exciting, sometimes crazy, time and Hetzel sought to record every detail.

In assembling a portfolio of Hetzel's work, several exclusions were made. Examples of his many portraits are one example. And the popularity of his sand hill scenes make them almost cliche in the Valley today. Instead, the images presented here depict Hetzel's wide diversity of interests and represent his awareness of his subject matter. He was not interested in submitting himself as a social critic. Instead, he was comfortable as the visual recorder of a community of characters he loved who tamed a landscape in which he found beauty. In that sense, his contribution to the Valley's historical awareness was profound.

INTRODUCTION

Leopold Hetzel was born into a musician family. His father, George Washington, was a pianist, trombone player, composer and leader of several musical groups. George Washington Hetzel (born on the Fourth of July) was leader of the Royal Hungarian Symphony in Budapest and later became the composer for the band at the Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. His published music included such ditties as the Golden Gate Waltz, Yosemite March and Washington Avenue March, all written in the 1890s.

He met Katherine Handycides while on tour in 1876. Katherine was a modestly acclaimed musician with the stage name Madame Camille. The cornet player from Scotland had met and played before both Queen Victoria and King Edward Vll of England. George Washington Hetzel married Katherine Handycides in 1870.

On another tour, this time in the Orange Free State (now South Africa), Katherine gave birth to their first and only child, Victor Leopold Hetzel. He was born Nov. 18, 1877 in Port Elizabeth.

Leo„he hated Leopold„was born of means and raised to appreciate the social and cultural arts. Before reaching school age, he visited many of the world's cultural centers with his parents. His early life was relatively uncluttered and happy. But at the age of five, Leo fell from a high fence near his London home and severely dislocated his right hip. His parents were told by a host of doctors that amputation would be necessary, a verdict they refused to accept. The family returned to the United States to visit a "progressive" doctor in Denver who assured them the leg could remain if treated under his care. The injury did leave Leo with a pronounced limp throughout the rest of his life.

The Hetzel family then moved to San Francisco, where George Washington enjoyed a lengthy tenure with the Golden Gate band and where Leo began his schooling. In his adult life, Leo would remark that he regretted his parents were not very stringent in developing his own musical talent. At age 14, however, he began toying with a box camera and photography quickly became his avocation. He travelled about the Pacific Northcoast after leaving school and supported himself by shooting photos of proud loggers posing in forests. (His early work in the Northcoast has not been located, according to his family. )

After several years leading a life of gypsy photographer in the woods, he returned to San Francisco. Not long after his return, his father died of a heart attack. Funeral services were held on Leo's twenty-first birthday.

Having refined his photographic skills in the wild timber country, Leo moved to Los Angeles soon after his father died to work for Hartsook Studios.

STELLA DAVIS

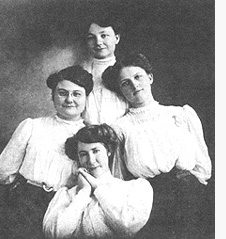

Stella Davis was born in the small farming community of Graham, Missouri on Aug. 29, 1881, the first of nine children. When Stella was 19 and had completed two years of college, she and her family moved to Porterville, California, where her father became an orange grower. In August, 1907, she and her three best friends travelled to Los Angeles with the mission of seeing as much of the world as possibie before settling down to the security of marriage and the family. At the time, Stella was engaged to hometown football hero Burt Keene.

During their trip, the girls stopped in Hartsook Studio for a souvenir portrait of their time in Los Angeles. Leo Hetzel was their photographer and, the girls agreed, a handsome one at that. Leo turned on his worldly charm and, indeed, the country girls were impressed. Several days later, when they returned to choose their prints, Leo made it a point to wait on them. On their final full day in Los Angeles, they stopped at Hartsooks to pick up their prints. Once again, Leo was there to help. He pulled Stella Davis aside and asked if she would mind him seeing her off at the train terminal the following day. She flushed, giggled and said of course not, completely sure he would never show up.

But he did.

At the train station, they promised each other they would exchange correspondance. Stella returned home, ended her engagement to Burt Keene and continued a long distance relationship with Leo. On April 29, 1908, Stella Davis married Leo Hetzel.

The newlyweds remained in Los Angeles for several years, settling into a cute clapboard home on Kingsley Drive. Within two years, Stella gave birth to the couple's first child, Victor. Leo, meanwhile, labored for Hartsook Studio, taking home an adequate salary.

He missed the outdoor life he had come to love in the forest, however, and one day came home to announce he had purchased property on Big Bear Lake and his intentions of eventually building a home there. He bought camping equipment and spent a weekend under the stars on Big Bear Mountain with his wife. But petite Stella hated nature's elements and insisted Leo dispose of his Big Bear acreage. He unloaded the property almost immediately but yearned to get away from the City of Angels, which was growing faster than most folks could keep up.

THE TRAVELLING SALESMAN

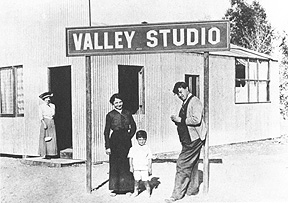

In 1913, a supply man for the Eastman Company made a routine delivery at Hartsooks and Hetzel handled the delivery. The salesman told Leo he had travelled Southern California extensively but had never seen any single area with as much potential opportunity as the Imperial Valley. The supply man's comments came at a time when Hetzel yearned to establish some independence from a weekly salary and a boss. Talk of Imperial Valley interested him. So in September, Leo departed Los Angeles in his Thomas Touring Car to discover the untapped desert himself. Near Seeley, his car broke down. A group of passersby stopped to lend their hands and towed his car to El Centro. It was hot and muggy but the good samaritans refused payment for their efforts. Hetzel, impressed with the good will of those who had helped, stayed in El Centro for a period and noted the friendliness of the samaritans on the highway was not an isolated case in this rugged little town. He established a home and studio in a tin building on the corner of Sixth Street and Broadway before summoning his wife and child to join him.

EL CENTRO

Cabarker was actually one of the latter communities in the Imperial Valley to be established. In fact, developers in the community of Imperial were outraged when W.F. Holt, the Redlands capitalist who had already established the town of Holtville, decided to locate the Valley's major rail junction midway between Imperial and Holtville rather than Imperial. Holt and partner C.A. Barker bought 320 acres at the rail intersection for $40 per acre from A. R. Robinson and finished townsite maps for subdivision and sale of lots. As the Valley's ma jor rail intersection, they had no trouble selling land in Cabarker, a town named after Holt's partner in the land deal. By and by, the practical nature of the community's locale transcended C.A. Barker's ego and the townsite's name was changed to El Centro (Spanish, of course, for The Center).

Within only several years, El Centro had muscled Imperial out as the Valley's most important city. The rivalry between the cities was intense and when the Valley seceded from San Diego in 1907, the fight for the honor of housing the county seat became furious. The importance of the county seat was no small matter for the struggling Valley. County business offices would attract private business and industry and would offer a valuable base for growth. The prosperity of the respective communities was the bottom line in the campaign for the county seat.

Fortunately for El Centro's cause, Holt owned the Imperial Valley Press located in El Centro and hired a master of propoganda when selecting Denver Pellet as editor. "There will be absolutely no excuse for Imperial when El Centro gets the county seat," Pellet wrote. He added that Imperial Valley is situated on "worthless and impoverished soil..., the worst in the Valley. We shouldn't feel it necessary to have to apologize for our county seat." When Edgar Howe, editor of the Imperial Standard, attempted to defend his city, Pellet discounted Howe's "vile and blasphemous billingsgate. Imperial is certainly unfortunate in many ways, but in no way is it more unfortunate than in having this maggot foisted upon them to edit their paper."

On August 6, 1907, some 1,326 eligible voters from throughout the Valley cast their ballots and El Centro was selected the county seat by a 108-vote margin. As expected, El Centro thereafter thrived.

ESTABLISHING A STUDIO

El Centro was the Valley's bustling community by the time Hetzel arrived with his camera and Hetzel had no problem finding work. He was not the first photographer in Imperial Valley; John Weinert holds that honor for establishing a photography studio in his Imperial home in 1903. L. Van Burkelo pitched a tent near the El Centro Hotel in October, 1907 to become El Centro's first photographer. But by 1913, there was plenty of room for competition.

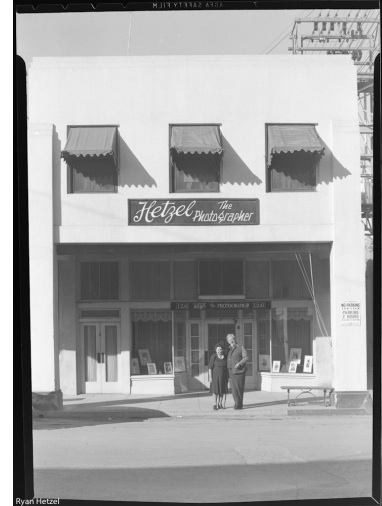

Dr. Thomas O. Luckett, meanwhile, also heard rumors of Imperial Valley's potential and came to El Centro from Los Angeles to establish a practice. He built a two-story brick building at 126 South Fifth Street. The doctor agreed to design a studio and living quarters downstairs for Hetzel. At Hetzel's request, in fact, Dr. Luckett had designed a tremendous skylight in the camera room so Hetzel's portrait work could be done with natural light. The photographer preferred working with natural light whenever possible. In March 1915, the Hetzel family moved into the studio/home and Dr. Luckett opened his medical office upstairs. Four years later, the Hetzel family moved upstairs when Dr. Luckett returned to Los Angeles.

The doctor may have become wary of Imperial Valley when a frightening earthquake rocked the area only four months after his new building was constructed. At the time, Hetzel had been across the street to deliver photographic work to Valley Drug Store. When the quake hit, several root beer barrels toppled over, splattering Hetzel. He ran back to change his pants and, midway through the change, a second quake struck. By then, his family had jumped into the family car parked in front of Hetzel's studio. As Hetzel ran out of the studio, the front facade of the building crashed down on his car. Stella Hetzel pulled Victor out of the car and the two miraculously escaped in jury, though the crashing bricks did scalp off the top of the Thomas.

Without a top, Hetzel converted the car into a sports convertible and drove it that way to the World's Fair in San Francisco several weeks later.

Hetzel enjoyed travelling about in his automobiles and was an active advocate for the building of highways. He was a member of the Broadway of America Association, a group dedicated to linking Broadway in San Diego to Broadway in New York City. He and his family often ventured in motorcade tours with the group. He also belonged to the California Chamber of Commerce, serving on committees connected particularly to the development of highways in the state. The automobile also served as a means to escape the summer's heat of Imperial Valley. "I don't think we ever spent a full summer in the Valley," said Virginia Kirk, Hetzel's daughter.

Virginia was born March 17, 1916, ten months following the earthquake. Delivering Virginia into the world was Dr. Luckett, assisted by Dr. L. C. House.

THE 'FAMILY'

Mullarky married Maye Purdy in 1927 and decided to strike out on his own. "He didn't want mother and daddy to think he was ungrateful," Virginia said, "but he felt he wanted a studio of his own." His search ended in Gallup, New Mexico, where Mullarky found a studio to settle down in.

When Mullarky left, the Hetzels replaced him with Lauren Elkins and later with Jack Baker. Baker worked for the Hetzels for many years before becoming a postal employee and later a postmaster in Porterville. Roy Sweeney was hired on after Baker. By that time, Virginia was in high school and Sweeney was a classmate with good photographic talent. Sweeney married Rosemary Daniels and eventually claimed fame for successfully lobbying the state of California to place drivers' photographs on drivers' licenses. When he left Hetzel, he was replaced by Juanito Lazo, who went on to become chief photographer for the Imperial Valley Press.

While Hetzel's assistants were indespensible, the rest of the family was also heavily involved in the business. "It was very much a partnership," said Virginia. Stella Hetzel did much of the book and paper work. Victor carried buckets of ice to the darkroom when he was available„darkroom chemicals needed to remain cool and Hetzel would purchase up to 300 pounds of ice every other day to meet temperature requirements. When Virginia entered high school, she assisted her dad in the portrait work. She and her mother would "color" some of Hetzel's scenic views. Stella Hetzel also helped "retouch" Leo's portraits.

COMMUNITY MEMBER

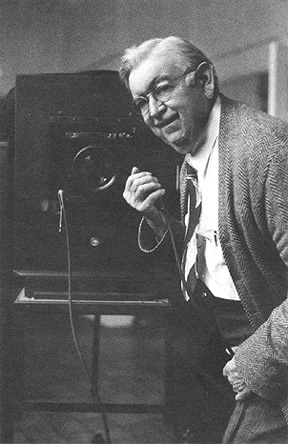

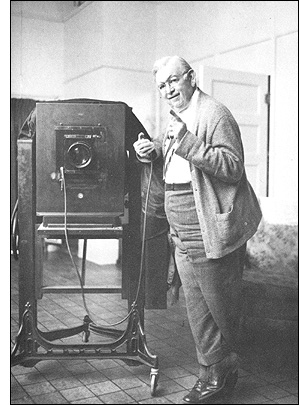

Hetzel's advertising motto was "Anything in Photography" and the man with the big box camera covered all of Imperial Valley with just about any service possible in photography. He "shot" property for farmers and surveyors, corpses for the coroner and stores for businessmen. It was work he enjoyed because it got him out of the darkroom and among his friends. In his middle years, Hetzel bore a striking resemblance to William Jennings Bryan, the popular orator of the time. While Hetzel could not possibly match Bryan's golden tongue, he is remembered as a good speaker with a jolly sense of humor and a sharp wit. Surely, his involvement in the El Centro Chamber of Commerce was a measure of Hetzel's popularity among the city's upper crust. He served two consecutive terms as Chamber of Commerce president from 1928 to 1930. When first elected, an Imperial Valley Press editorial stated, "El Centro has no citizen more sincerely devoted to its welfare than the new president who has ever been active in civic affairs and has the regard and respect of all who know him."

The family moved into a building designed especially for a ground-floor studio. They remained there until Hetzel's death in 1949. During his tenure as chamber of commerce president, the chamber levied a "tenmill tax" among members to help the organization engage in a wider field of activity. Hetzel also called all civic and official organizations together so that they could better coordinate their activities, as events planned by various organizations often conflicted. The meeting led to the formation of a scheduling council and Hetzel was selected president.

Hetzel was also active in the state Chamber of Commerce and his passion for touring automobiles naturally led to his active participation in the state chamber's road and highway committee. He was also appointed to the Imperial County Fair Board of Commissioners and was a trustee for the El Centro Elks Lodge.

Hetzel spent a lot of time in Imperial Valley's schools, also. His family remembers that he loved children and portraits of children were good studio business. Hetzel shot a lot of them. But he also lugged his camera equipment to Imperial Valley schools each year for official school photographs.

As Hetzel's wealth accumulated, he decided to diversify his investments a bit and bought several hundred acres of farmland south of El Centro. Hetzel grew grapefruit and alfalfa there for several years, a venture not particularly profitable once the Depression hit. At that time, he was faced with the loss of either his farmland or his studio. "He came out of the Depression relatively well," said Victor Hetzel, "though he came out of it without his ranch."

So Hetzel stuck with photography and is remembered as a "bread and butter" photographer. His freelance contracts with local businessmen, his portraiture and his film development service„in which he developed rolls of film deposited in Imperial Valley drug stores by amateurs„kept him busy and comfortable. "We never did without," Virginia said.

He was also devoted to the outdoors and to the progress of Imperial Valley and wanted to capture his passions on film. He spent much of his time in the desert, shooting wildflowers and cactus as well as the building of the old plank road and the Boulder Dam and the All American Canal and Valley communities.

Valley pioneers still display Hetzel's desert shots in their homes.

On October 28, 1944, an Imperial Valley Press columnist who called himself the "Rambling Reporter" honored the Hetzel business with kind words in his column. "It is with a great deal of pleasure that RR presents Leo Hetzel, veteran photographer, with a big bouquet of desert lillies," he wrote.

"The occasion for the award is the thirty-first anniversary of his arrival in El Centro. He has been busily engaged in taking photographs and pictures in El Centro and surrounding areas since October 28, 1913.

"His cameras have recorded the likeness of hundreds and hundreds of men, women and children. His photographs of desert scenes are famous everywhere. He has taken the pictures of Imperial Valley servicemen in two world wars. He has photographed the classes year after year in many schools in the Valley.

"And by his side all this time was Mrs. Hetzel. We think wives are entitled to something extra, extra special. To her we award a delightful nosegay containing one blossom of all the flowers she loves best.

"Many happy returns to this beloved El Centro couple."

Hetzel remained active in his work to the end. On June 16, 1949, J.C. Penney's held a grand opening of its new El Centro store at Fifth and Main streets. The photographer was extremely proud of the new store. It would occupy a building that had been vacant for nine years, since the 1940 earthquake levelled the El Centro Drug Store. He spent the entire day shooting pictures of the grand opening. On the following day, Hetzel suffered a heart attack.

He was admitted to the hospital, the first time he had been placed in one since his childhood fall from the fence. He hated it. "Just send me to Burt Lemon's," Virginia remembers her father telling her from the hospital bed. Lemon was El Centro's mortician. On July 6, another heart attack killed Hetzel in the hospital. His partner in family and business, Stella, followed him in death by heart attack September 13, 1950.

"Hetzel is accredited with having 'shot' every interesting spot and most of the interesting inhabitants without being convicted of anything but turning out first class, artistic work," read Hetzel's obituary in the Imperial Valley Press following his death.

FOLLOWING FOOTSTEPS

None of Hetzel's heirs now live in the Imperial Valley but his photography obviously left an impression on their lives. Virginia married Jake Brown, a Brawley cattle rancher, and their union produced three children, Patricia, Carolyn and Michael. Jake died in 1969 of a heart attack and Virginia is now remarried and living in La Jolla.

Victor is married and has two children, Leo and Ralph. Leo not only carries his grandfather's name but has also followed in his footsteps as a professional photographer. He spent several years as a free-lance photographer in South America and is now a newspaper photographer in Orange County. Victor and Ralph have also enjoyed photography and, according to Virginia, "have a beautiful collection of photographs from all over the world."

While the Leo Hetzel name is still very active in the profession, the building constructed by Dr. Luckett for Hetzel in 1915 is still being used as a photographer's studio and living quarters. In 1950, Warren Rhodes bought the building from the Hetzel estate and spent several years utilizing the studio. At that time, Rhodes discovered thousands of Hetzel's glass plate negatives (used in Hetzel's first decade in the Valley) and acetate film negatives. The acetate film negatives were deteriorating and created a serious fire hazard. As a result, most of the acetate film was destroyed.

Negatives that could be salvaged were filed for many years in the Imperial County Courthouse in El Centro by Art Sinclair, one of Hetzel's longtime friends. The negatives were then moved to storage in a building near the Imperial Airport that once housed the now-defunct Imperial Valley Development Agency. When the development agency disbanded, the negatives were moved to Spencer Library in Imperial Valley College, where they are still stored. They can be checked out as if they were books borrowed from the library, though special permission from the Hetzel estate is needed if the negatives are used commercially.

After several years, Rhodes sold the building to Douglas Bliven. The master photographer has continued the photography tradition at 126 South Fifth Street in El Centro for almost 30 years. The building has withstood earthquakes and fires which have levelled surrounding buildings.

Bliven's training in the profession was garnered at the New York Institute of Photographers and he says his work was inspired by Yosef Karsh. He worked in studios in Minnesota and San Fernando before purchasing his El Centro studio in the early 1950s.

As professional heir to Hetzel, Bliven has had numerous opportunities to work with many of the negatives Hetzel left. Some of Hetzel's equipment is still in use at the studio, including a movie camera and the camera stand Hetzel used to mount his portrait camera.

Bliven reaffirms that Hetzel was a "bread and butter photographer. He was a well-trained photographer who did competent, everyday type of work.

"He gave a good straight-forward presentation of what was before him," Bliven said. "He felt his job was to give a good, clean job to the public."

In working with Hetzel's negatives, he said he found them consistently dense. "He could have come from the school which believed in overexposure," Bliven said. If a negative is overexposed, it is easier to work with the negative and to dodge out blemishes or burn in highlights, creating more a flattering work for certain persons and places.

Bliven said Hetzel was a "businessman first and then a photographer. He was not an artist; I never heard of him winning a top award."

In fairness, however, Bliven added that few photographers of his era considered themselves artists. He said, however, that Hetzel's work indicates he was well aware of his responsibility as an historian.

"He was a recorder of history and he was smart enough to know it," Bliven said. "If we didn't have his images, what would we have? Just words."

| |