R E A L LIFE MAGAZINE

No. 18, Summer 1985.

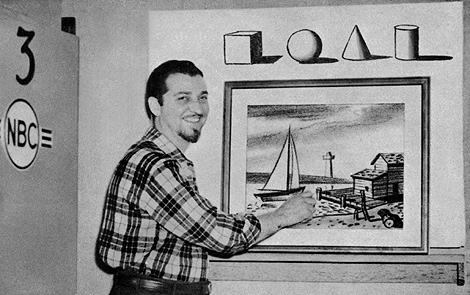

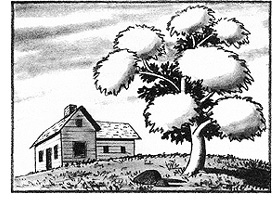

One of You by Susan Morgan The descent from radio to television is certainly not as great as from bridge to canasta. The post war world was full of promise. In May of 1946 NBC placed a sixty one foot antenna atop the Empire State Building and kept one promise made in the 30's and postponed during the war years—television. Reaching out over an area of 80 miles, the first regularly scheduled program was Radio City Matinee. Adapted from radio to a video format, it was an emceed variety show. Each act was about ten minutes long; Maggie McNellis modeled funny hats, a Mrs. Smith demonstrated flower arranging, an architect moved miniature furniture around a table-top room while giving home decorating tips, a comic told jokes, a chef whipped up a treat, and Jon Gnagy began teaching America how to draw. On the first episode, Jon Gnagy, sporting a goatee, wore an artist's smock and beret. He led the viewing audience through his step-by-step method to make a drawing of an old oak tree. His crayon melted under the studio lights, his chalk squeaked, but in seven minutes the lesson and the picture were completed. "You were great! Your show is pure television!" exclaimed the production manager.  In 1946, in the metropolitan broadcast area, there were about three hundred television sets. Similar to the recent marketing history of home computers, the sets belonged mostly to buffs, scientists and researchers with a predilection for new technologies, before attracting a wider public. When the first regularly scheduled programs appeared, an average of seven viewers per set watched, paying attention to a new presence in American life. The regularly scheduled programs continued and multiplied. This was no insignificant fad, television began taking its place in the living room, arriving in never faltering numbers. The baby boom was on and the television industry was booming right along with it. This was an era of change and optimism. And television was its invention. Along with every communication innovation since the printing press there has co-existed the hope for greater democracy, in providing low cost access to information to a greater number of the population. In 1946, there were 15,000 televisions in the entire United States, by 1949, 3 million. By 1961, there were more televisions than bathtubs in American homes.  By the autumn of 1946, Jon Gnagy had become so popular that NBC gave him a show of his own. The first television show produced the first spin off. After the first episode, Gnagy never wore the artist's smock or beret. This artist was neither foreign nor elitist, no Jose Ferrer saying oo-la-la and wearing shoes on his knees as he roamed about the Moulin Rouge. This was a plain speaking Midwesterner dressed in a plaid shirt and dark trousers. The format of his show was so simple—one character in a single, shallow set, and a minimum of camera angles—that it became a training ground for all the new directors, camera men, and sound technicians starting out in a burgeoning industry Here was a show that was accessible to everyone and it was called You Are An Artist. I believe that you are an artist. I believe that everyone is an artist. When I say this I am not trying to be sensational. I merely state it as a conviction which has been proving itself for years in my beginners' art classes. Everyone is an artist because everyone is a camera. Every sunset you have ever seen, every interesting old man, or beautiful woman is recorded in your brain. In fact, everything your eyes have looked upon during your entire lifetime is imprinted in your brain as surely as is a picture on film or sound on a record. And there is a way by which you can bring these pictures in all their clarity and brilliance, out of your brain to your fingertips and on to paper or canvas. Everyone is an artist because everyone is a camera. Every sunset you have ever seen, every interesting old man, or beautiful woman is recorded in your brain. In fact, everything your eyes have looked upon during your entire lifetime is imprinted in your brain as surely as is a picture on film or sound on a record. And there is a way by which you can bring these pictures in all their clarity and brilliance, out of your brain to your fingertips and on to paper or canvas.

—Jon Gnagy The story of Jon Gnagy's early life is the stuff that Frank Capra movies are made of. He was born in 1907 in Varner's Forge, Kansas. He grew up there as a member of a Mennonite Community. (The Mennonites oppose military service and the acceptance of public office, they disavow vanity and fancy dress. They are largely self-reliant and continue to practice a nineteenth century crafts tradition.) In this straight forward, hardworking environment, Jon Gnagy began making pictures. Portraits were tantamount to idolatry according to the Bible, so he made drawings of the farm and the Kansas landscape that were good enough to win prizes at the State Fair art shows. "When I was satisfied that I had achieved both, I decided that what I wanted most was to give this knowledge to others. The desire to express is in everyone, and if people are shown logically how to materialize an idea, then their inspiration grows and gains momentum and they work intuitively and have a swell time of it. There is nothing like the supreme satisfaction that you get from being able to express objectively something that is subjective and nebulous. That's what art is, the expression of unconscious feelings in an objective form." In 1939 Gnagy read about Vladimir Zworykin's experiments in television and decided television was the "ideal teaching medium". Seven years later, Gnagy was on the air, teaching "the world's largest art class". To evoke in oneself a feeling one has once experienced and having evoked it in oneself then by means of movements, lines, colours, sounds, or forms—transmit that feeling that others experience the same feeling—this is the activity of art.—Leo Tolstoy, What Is Art?,1897 May I repeat what I told you here: treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone, everything in proper perspective so that each side of an object or a plane is directed towards a central point. . .—Paul Cezanne —introduction to Learn to Draw  It's not a recipe, it's a mix. It's not a recipe, it's a mix.

Jon Gnagy's show began with the camera panning a charcoal drawing of the four basic shapes. The theme music was Strauss' Artist's Life. And so, the lesson would begin. Gnagy was a natural teacher, confident and patient. He did not present himself or his skill as superior. His method was essentially humanistic rather than didactic, he invited the viewers to join in rather than study. His accent was not distinguishable, it was a flat American accent that couldn't be assigned to a particular region. He lived in the television set and visited us in our homes, an artist who believed that everyone could be an artist. He emphasized that the lesson was easy and interesting and he addressed his audience as "each and everyone of you". With deft strokes, Gnagy would create images of a vanishing America—haystacks in the moonlight on Halloween night, stone watermills, covered bridges, happy boys sledding down snow covered hills, a single sailboat moored in a natural harbor. He treated his subject matter with such a direct familiarity that it seemed in no way uncommon. He discussed the branch formation of a giant elm tree or the patterns of migrating birds with an audience that may have never seen such things. But he did not treat this information as rare or even particularly personal. It was an egalitarian presentation of information. Nowhere in the show was there a suggestion of doubt, no question that the audience might not know these things nor draw so skillfully as he. There was no randomness in this art-making. The method was prescribed, step by step. All objects were drawn using the four basic forms; shadows were cast from a single, strong source of light. When the picture was finished, a frame fitted with a mat would be placed around it and the freshly made art was ready to go.  The post-war world was rife with the idea of a homogeneous individuation. Everyone could own an individual home, but each house was identical in the contractor's development. On the highways Howard Johnson's served the same twenty eight flavors and HoJo cola, sold the same magnetic Scottie dogs and smoking pets in restroom vending machines, in identical restaurants located miles apart. There was something strange and comforting in that recognizability. The foreign became assimilated, made bland and American, like frozen Swiss steak or French fries. Unidentified 'classical' music was reworked into pop tunes or movie themes, served up like frozen foods, bearing little resemblance to the original. And everyone could draw their own picture exactly like the one that Jon Gnagy made on television. Possibly that was what made the show one of the most popular and longest running in television history but Gnagy's contribution had far nobler intentions than the progenitors of such debased concepts as Pour-a-Quiche and the anywhere-USA style shopping mall.  Jon Gnagy introduced to American families the idea of being an artist, an idea that was not couched in terms of privilege or preciousness. All of his references were incorporated subtly, informing his teaching method rather than exalting the past. He was sharing some first hand knowledge at a time when television viewing still had a sense of intimacy and concentration. To go along with his television show, Jon Gnagy produced a kit of art supplies and a book of drawing lessons. The writing style is direct, outlining his plan. The chapter titles are terrible puns, the sort of jokes one forgives a favorite uncle for making (While There is Still Life There is Hope, How To Get A Head By Going in Circles). At the end of the book, he wrote "The plan I have outlined in this book will be invaluable to you. It will release the creative drive in you and set you free. . ." That was Jon Gnagy's plan. A lot of people growing up in the fifties watching television got the idea.  |

Articles on

Jon Gnagy

Visit:

The World of

Jon Gnagy

He worked at a newsstand, got a job making posters, and at eighteen became the art director of a small advertising agency. He was married at twenty to his eighteen year old assistant. They moved to Wichita the following year and had a baby girl. They moved to Kansas City and got a better job. Luck was with them and they decided to try New York. They arrived in 1932, "not having heard there was a Great Depression on". They had a baby boy and lived over a steam laundry in Flushing. Their luck was running out and Jon Gnagy had a nervous breakdown in 1935. They left the city for New Hope, Pennsylvania. Gnagy described that period of his life when he was ill as being " . . . acutely sensitive to suggestions, I had a great many artistic inspirations. As soon as I became well, I tried to express these inspirations on canvas but I found I lacked the mechanical know-how. For years after that, I spent my evenings and weekends studying philosophy, psychology, physics, and physiology in an effort to obtain the know-how and to find, if I could, a key to esthetics.

He worked at a newsstand, got a job making posters, and at eighteen became the art director of a small advertising agency. He was married at twenty to his eighteen year old assistant. They moved to Wichita the following year and had a baby girl. They moved to Kansas City and got a better job. Luck was with them and they decided to try New York. They arrived in 1932, "not having heard there was a Great Depression on". They had a baby boy and lived over a steam laundry in Flushing. Their luck was running out and Jon Gnagy had a nervous breakdown in 1935. They left the city for New Hope, Pennsylvania. Gnagy described that period of his life when he was ill as being " . . . acutely sensitive to suggestions, I had a great many artistic inspirations. As soon as I became well, I tried to express these inspirations on canvas but I found I lacked the mechanical know-how. For years after that, I spent my evenings and weekends studying philosophy, psychology, physics, and physiology in an effort to obtain the know-how and to find, if I could, a key to esthetics.