|

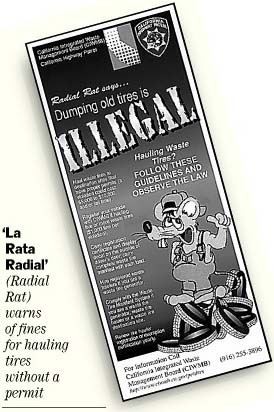

Environment Cerro Centinela — Mexico's 'Tire Mountain' — Worries U.S. Neighbors By Joel Millman MEXICALI, Mexico — When the rubber leaves the road, there's a good chance it will end up in this sweltering city on the U.S.-Mexican border. Mexicali is becoming the used-tire capital of North America. About five million old truck, car and motorcycle tires litter the city. Most were manufactured and sold in the U.S. The growing population of tires — at least four for each resident of Mexicali — is worrying officials in California's Imperial Valley, the lush agricultural region just across the border that produces much of the state's lettuce, alfalfa and hay. Tire dumps have a nasty habit of turning into tire fires, which sometimes burn for years. One such fire upstate, in Tracy, Calif., has been smoldering since the summer and already has cost California taxpayers more than $1 million. "When millions of tires catch fire, they melt, and the pyrolytic oils seep into the water table," says Gerald Quick, head of environmental health services for Imperial County. "The smoke plume goes all over, and that could contaminate the valley's crops — something like $1 billion worth of damage. That's a devastating event in any man's language." Yet the tires just keep on arriving here in Mexicali. That is despite the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement, which was supposed to be, among other things, a forum for resolving just such binational environmental concerns. Officials of the North American Development Bank, the NAFTA unit that could fund a cleanup, say that while they are aware of the problem, they can finance only revenue-generating programs. So far, they haven't seen one for tire recycling that makes economic sense. That would surprise many people here. Recycling tires is a border tradition. Registered retreading shops, known as llanteros, buy discarded tires in the U.S. for $3 to $5 apiece, then patch and resell them. At $20 or so, they are a bargain compared with new tires, which can retail for $100 or more. But because they last only a few months, motorists quickly replace the retreads with "new" ones, feeding a cycle that contributes to the growing piles of junk. In the meantime, tires waiting to be patched litter dry riverbeds and pile up under highway bridges. Some are used to hold down tin roofs or are buried halfway in the ground as makeshift fences. Many eventually will be sold to sidewalk vendors, who offer them to motorists for a few hundred miles of use. When the last patches finally give way, the tires are rolled out to the desert for illegal internment on Cerro Centinela, Mexicali's Tire Mountain. "We still don't know how many tires have accumulated here," says Moises Rivas, an engineering instructor at the Autonomous University of Baja California, the state of which Mexicali is the capital. This week, Mr. Rivas hopes to finish a census of Mexicali's Tire Mountain, which is really a pile of rubber ringing the slope of a mesa west of downtown. As soon as authorities know how many tires, he says, they will know how much it will cost to remove them. But the tire study, which is being assisted by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and California's environmental officials, won't solve the problem of how to stop the tire onslaught. The rapid buildup of Mexicali's dump is a relatively recent event. The booming border manufacturing industry is one reason; growing U.S.-Mexico trade is another. "The border area is becoming more affluent, and Mexicans are flocking to the border because of better jobs," says Geoffrey Silcox, a fuels-engineering specialist with the University of Utah and an expert on the disposal of old tires. He says the increase in that population, plus the increase in disposable income, inevitably means increased demand for used tires. To satisfy that demand, Mexico has exempted the states of Baja California and Sonora from a regulation prohibiting used-tire imports. Under the exemption, Sonora imports about 80,000 used tires each year, but only at one spot along the border. Baja's llanteros are allowed 600,000 imports a year. The higher quota for Baja, say state officials, was set because the state's border cities are growing so fast. Yet a survey conducted by the California Integrated Waste Management Board, a state agency, indicates over a million used tires — far more than the import quota — are exported to Mexico annually. In addition, used-tire dealers from as far away as Kansas City and Denver say Mexican llanteros are buying their tires, then bribing Mexican customs agents to look the other way. "Mexicans come every week — they're our biggest customers," says Jerry Jamison, president of Tire Mountain Inc. of Hudson, Colo. "Anyone who buys from me pays a bribe to get them across the border. The bribe probably costs more than the tire." Jose Domingo Vigil, president of the Baja Tire Vendors Federation, says his members don't break the law. "We pay our taxes and abide by import rules," he says. But according to Mexico's National Association of Tire Distributors, as much as 20% of tires sold in Mexico are retreads from the U.S. "They bring them in there in Baja and sell them all the way to the Yucatan," says Ruben Lopez, head of the organization in Mexico City. While trying to crack down on the illegal traffickers, Mexicali officials have licensed a tire-shredding company, Grupo Llanset SA, to operate a disposal site near Cerro Centinela. Tires are ground into "crumb," a goulash of steel fiber and rubber, and then shipped to a factory north of Mexico City where their components are cryogenically extracted. Grupo Llanset charges dealers 65 cents a tire to dump unsalvageable wares, but has shredding capacity for only about 2,000 tires a day, which is about the rate at which tires are entering the state. The crumb, though not high-quality, does have other uses, such as in the rubber mats found in playgrounds. Meanwhile, the California Highway Patrol has started distributing leaflets to tire haulers bound for Mexico. The leaflets, featuring the cartoon character La Rata Radial (Radial Rat), warn that haulers of waste tires must have proper permits, or risk thousands of dollars in fines. One California dealer, Lakin Tire West Inc. of Los Angeles, has offered to take back from Mexico any old tires it has sold once they can no longer be repaired. Lakin, which will send more than 300,000 used tires to Baja this year, says so far no one has taken the company up on its offer.

|