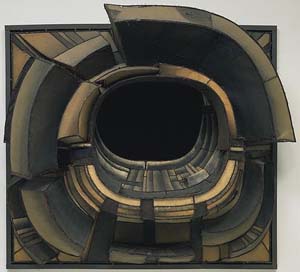

Allan McCollum, Collection of Forty Plaster Surrogates, (1982/84), enamel on cast Hydrostone, on view in 'What Is Painting?' at the Museum of Modern Art. |

|

Step 1: Buy Paint. Step 2: ? By DAVID GROSZ Once upon a time, we knew what painting was. As recently as the 1960s, there was, if not a single consensus, then at least several broad and overlapping consensuses about what constituted a painting: It was two-dimensional and used pigments on some type of support, like a canvas; it was abstract, or it was representational; it was defined by its medium and sought to exclude the influence of all others, or it was defined by how prettily or truthfully it employed its medium, etc. |

|

A single canvas by Peter Doig, "Pink Snow" (1991), stands just outside the galleries, introducing the show and demonstrating how exuberantly powerful contemporary painting can be, despite its identity crisis. A Klimt-inspired, faintly expressionist take on a winter scene, it depicts an orange-faced skier on red skis standing before a large house in a storm of snow that is white but also red, green, yellow, orange, and black. |

Philip Pearlstein's rigorously perceptual brand of realism, here exemplified by the rather dour nude "Two Female Models in the Studio" (1967), has been largely influential to less stylistically affronting artists than those included in the exhibition. Still, the ripples of his influence extend, if faintly, out to Chuck Close, John Currin, and Pearlstein's old friend Andy Warhol. After a gallery that groups together '60s-era abstract influences on contemporary work, painting's center begins to disintegrate rapidly. In a room focusing on painting as an idea rather than a practice, John Baldessari's "What Is Painting" (1966Ð68) — which gives the show its title — presents nothing more than a text, painted, that ends with the coolly ironic statement: "Art is a creation for the eye and can only be hinted at with words." Baldessari's canvas is guarded by other genre-bending efforts, a Barbara Kruger Photostat using a detail from Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling, and an embroidered "painting," "Sampler (Starting Over)" (1996), by Elaine Reichek. |

Such fecund pairings flower abundantly throughout the show. The squeegeed blurriness of Gerhard Richter's photo-based oil "Court Chapel, Dresden" (2000) — a self-portrait with a friend — seems at first to contrast with the precise photorealism of Mr. Close's portrait "Robert/104,072" (1973Ð74). The nearer one gets to the Close, the fuzzier it becomes, and the farther one gets from the Richter, the more it resolves into focus. In places, figuring out the relationships between the works is half the fun. Repetition seems to unite Andy Warhol's multiple portrait of "Lita Curtain Star" (1968); Allan McCollum's "Collection of Forty Plaster Surrogates" (1982Ð84), a group of framed black rectangles of various sizes; Sherrie Levine's "Large Check" (1987) series of multicolored checkerboard paintings, and Richard Pettibone's hilarious set of 10 tiny, though faithful, replicas of Frank Stella's "Protractor Series" of paintings. |

Text paintings, German Neo-Expressionism, and Pop-inspired wackiness all receive their due here (though not, sadly, black paintings). By the time one reaches the last two galleries, a certain symmetry has been achieved: The penultimate gallery yokes together current representational styles and the final gallery current abstract works. Fittingly, one of the very last works one encounters, a 2006 untitled study of Xs by Wade Guyton, was made, not with paint, but with an ink-jet printer and canvas. Does the use of a printer mean its product is a print, a printout, or something else? Of course, the answer depends on definitions: In other words, What is a painting? This fine exhibition insouciantly suggests a painting is not what we are used to, not what we expect, but rather, whatever we can get away with. Until September 17 (11 W. 53rd St., between Fifth and Sixth avenues, 212-708-9400). |