Allan McCollum first made his Perfect Vehicles in 1985. Sitting atop plinths, the standard mode for the display of sculpture, the groupings ranged from five to fifty generic cast-plaster vases. The shape of the vase was that of an antique Chinese ginger jar, a shape made ubiquitous by centuries of its reproduction. The Perfect Vehicles came in a range of colors, such that even though each vase was identical in shape, no two groupings were alike based on quantity and color. Radically dysfunctional (they are solid and could never be used actually to hold anything), they nonetheless perform their domestic role as decoration. In so doing, they conflate the art object proper with its lesser partner, the objet d'art, suggesting that the shared function of the two categories is their presentation of taste and wealth within the domestic interior.

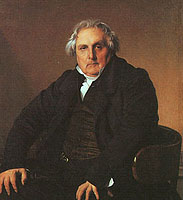

In subsequent iterations of the Perfect Vehicles, McCollum played with issues of scale. Maintaining the same shape, he enlarged the vases to human scale. This monumentalization of an everyday object had the strange effect of anthropomorphizing it. The shape took on both male and female characteristics, looking, on the one hand, like a plump and proud member of the bourgeoisie (they have always reminded me of Ingres's infamous portrait of Louis-François Bertin, 1832), and on the other, miming the sensuous curves of the female body. While the works connote the bodies of the living, they also recall funerary urns and as such bring death and its memorializations into the space of the gallery.

McCollum's use of casting is the structuring formal element of his work. For him, the cast is intimately connected with the representation of death. In a 1991 interview, he said:

If the Perfect Vehicles imply death through their form as well as through the process by which they are made, then Over Ten Thousand Individual Works does something slightly different. More than ten thousand objects lay on top of a mammoth table. All of a size to fit comfortably into the palm of the hand, they lie in seemingly endless rows, and while each is different, the effect is of a uniform mass, a totality. The work is produced from "hundreds of small shapes casually collected from peoples' homes, supermarkets, hardware stores, and sidewalks: bottle caps, jar lids, drawer pulls, salt shakers, flashlights, measuring spoons, cosmetic containers, yogurt cups, earrings, push buttons, candy molds, garden hose connectors, paperweights, shade pulls, Chinese teacups, cat toys, pencil sharpeners, and so on."2 This list of fragmentary readymades, unluxurious, mass-produced, and inherently quotidian, is a list of part objects and of lost objects. Replicas of these objects were made from casts and thus assembled according to a numerical system that ensures that each object is indeed individual. On the face of it, their individuality is assured, by the title, by a cursory glance at a corner of the table. One quickly senses, however, that attempting to verify this individuality could easily descend into madness. Despite the simplicity of the mathematical system, its very rationality appears irrational in the face of the infinitesimal differences of the individual objects. Over Ten Thousand Individual Works presents a spatialization of the reciprocity between bodies and things. The incommensurate nature of our lived reality as individual beings that have nonetheless been rendered equivalent to one another—we are interchangeable within the work place, within the market, as an audience for the mass media—is played out in the proliferation of mathematical difference that produces an effect of overwhelming similarity. That humans then adopt that similarity as a protective device is perhaps yet another thing we learn from the very objects we desire. If the Perfect Vehicles are imbued with a sense of death, a death that pervades our relationship to objects that threaten to outlast us, then the Individual Works are suffused with the struggle between reification and the experience of individuality that is a hallmark of daily life under capitalist mass production.

--------------------- 1. Excerpt from an interview with Lynne Cooke, New York, May 3l, 1991. Carnegie International 1991, Volume I. The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburg. Rizzoli, New York, 1991. Also available at: Lynne_Cooke_Carnegie.html. 2. As described in William S. Bartman, ed., Allan McCollum. Los Angeles: A.R.T. Press, 1996, p. 58. |