by Paul McMahon

It is rare that one says exactly what one wants say, so effortlessly and unself-consciously that the moment is past, like a flag on a slalom course before one realizes it. Similarly it is rare that one sees something one has always wanted to see and on seeing it is struck with its simplicity and directness, This is how I felt when the elevator doors opened onto Allan McCollum's installation at Marian Goodman gallery last March. My paintings are designed as "signs" for paintings, or as surrogates; they are meant to function in a way similar to that of a stage-prop, but in the normal world of everyday life. |

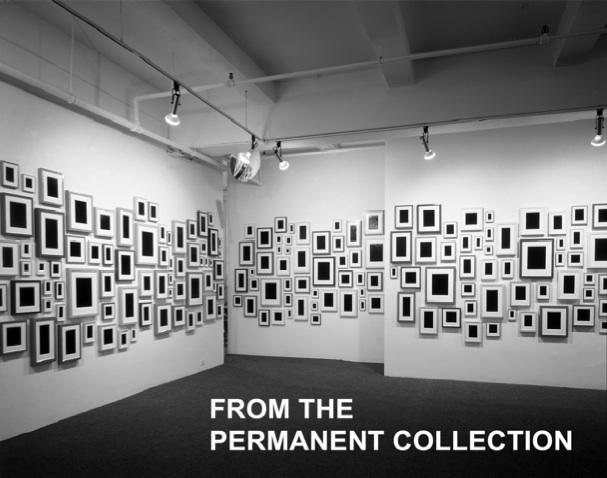

Like mannequins, McCollum's pieces look all right at first but then you realize that they aren't all there. They are merely dummies of framed pictures. McCollum takes a plain frame and a mat with a standard opening for a picture, sands down the sharp edges and covers the whole thing with many coats of paint. A few years ago he was painting them all one bright color. An installation at Artists Space looked like a row of jujubes. The current ones are colored 'naturalistically'. The frame part is painted an appropriate color for wood or metal, like brown, tan or silver, and the mat is painted white. Where the picture should be is painted black. The end result looks like a three-dimensional international symbol for an artwork. It is the most basic formula for a hanging picture. The irony is that there is no picture being presented within the frame. I am working to construct a charade, in which I am surrounded with false pictures: pseudo-artifacts which beckon me into the desire to look at a picture, but which are complete in doing just that, and that alone. |

Louise Lawler: Allan McCollum's studio, 1983 |

|

The effect is curious. Expecting to look at a picture, we are instead presented with a symbol for a picture, which brackets the experience. Instead of just looking we are made to look at the activity of looking. Although he is uncomfortable with the term Conceptual Art, there are clearly affinities, as conceptual work often strives to bring a healthy self-consciousness into the ritual of viewing art. Where this work departs from some of the recent (neo)conceptual work is in McCollum's accommodating attitude. Didactic in a positive sense, this show was not a heavy-handed political statement, nor was it couched in inaccessible intellectuality. Instead it engaged the viewer through humor and enticed one into the encounter McCollum intended. I am working to construct a charade, in which I am surrounded with false pictures: pseudo-artifacts which beckon me into the desire to look at a picture, but which are complete in doing just that, and that alone. In his writings McCollum speaks almost bitterly of dislocation, fraudulence and nightmarish aspects in the work. But I find the work to be accessible, humorous and astute in its construction and presentation. Far from being misanthropic, these pieces have a friendly and open attitude about them. They are there for us, totally receptive, like pets. And like pets they won't talk backbecause they have nothing to say. Their content is only what we see in them. They are molded by our desires, and specifically the desires with which we look at art. What are these desires? In looking at this work I felt satisfaction and a kind of pleasure that I've come to look at as my feelings toward art in general. I realized, or, more accurately, I remembered my trusting and optimistic attitudes about the true value of art. I uncovered my faith in art's abilities to communicate truth, beauty and wisdom; things I was taught and have never rejected. And I became aware that it is this faith that is constantly traded on in every art world transaction. That McCollum's work can reveal this mechanism makes it valuable indeed. |

Photo: Peter Bellamy |

Allan McCollum: Installation view, Chase Manhattan Bank lobby, New York, 1981. Photo: Mary Ellen Latella

Allan McCollum: Installation view, Chase Manhattan Bank lobby, New York, 1981. Photo: Mary Ellen Latella