|

Allan McCollum's Supplements, More or Less

MARYJO MARKS

| |

Just as the actor no longer has to persuade the audience that it is the author's character and not himself that is standing on the stage, so also he need not pretend that the events taking place on the stage have never been rehearsed, and are now happening for the first and only time.... He narrates the story of his character by vivid portrayal, always knowing more than it does and treating its "now" and "here" not as a pretence made possible by the rules of the game but as something to be distinguished from yesterday and some other place, so as to make visible the knotting-together of events.

Bertolt Brecht[1]

An artwork is related to every other object and event in the

cultural system, and the meaning of an artwork resides in

the role the artwork plays in the culture, before anything else.

Allan McCollum[2]

|

Foreground

What if an artist put on a show? It would require a stage set (gallery or museum) with special lighting; an author (the artist), director (art dealer or curator), and stagehands (art handlers); actors (the viewers) and audience (the same spectators, performing a dual role); playbills (press releases, reviews) and props (works of art). It would also need a script (aesthetic discourse) determining the action—although as a live performance, partly improvised, we should anticipate some deviation. This ad hoc production of an ersatz art show comes with a caveat: it should function simultaneously as a legitimate art exhibition. Its objects must exist, likewise, in both their "natural" or "authentic" state and in their theatrical or surrogate version. The whole thing might also encompass a range of seemingly extrinsic materials or forces. Supplemented with other objects and texts, contexts and influences, it would include the response of every viewer who ever saw it.

Background

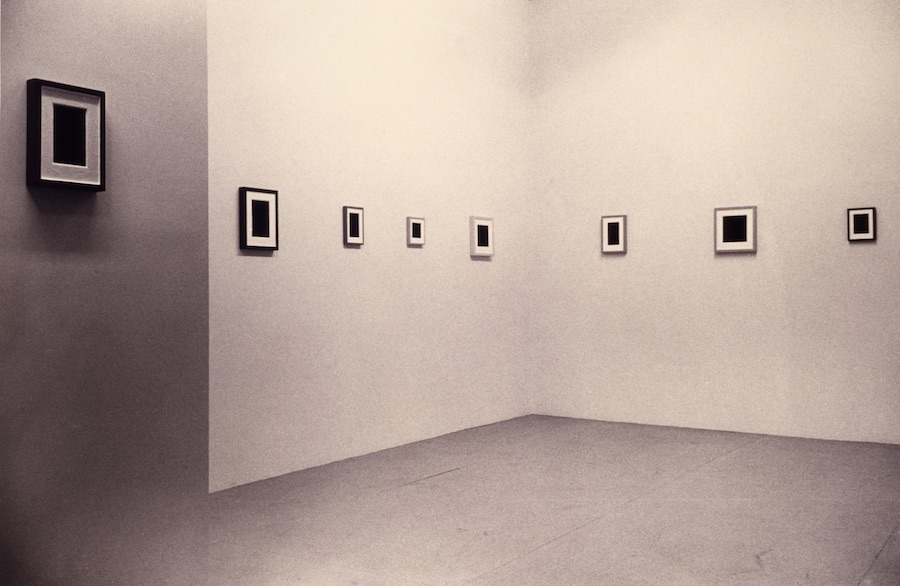

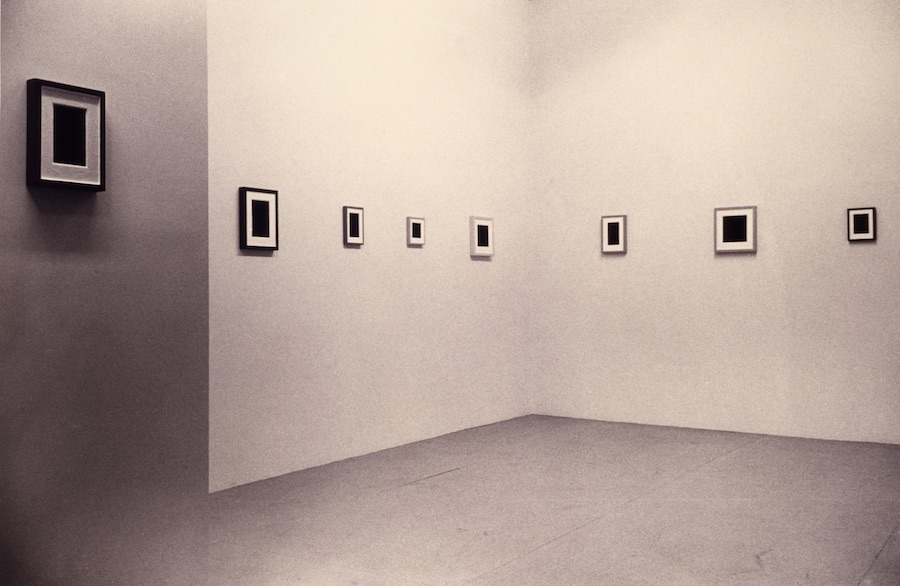

Allan McCollum began staging such scenarios with his installations of wood Surrogate Paintings (1978) and, later, Plaster Surrogates (1982), cast in HydroStone from molds. The works that comprise each series resemble any framed two-dimensional object typically hung on a wall, with a blank panel where image or text normally resides. Usually exhibited in vast quantities, they hang cheek by jowl, floor to ceiling, salon-style. This hyperbolic presentation type was a commentary on the grandiose sentiments of traditional art and the inordinate value, aesthetic and economic, accorded the singular unique artwork. Yet McCollum's work referred, then as now, to a broad swath of objects and settings beyond the province of high art. This was signaled by the definition for art, or similar objects, he frequently favored: the cultural convention of things "hung above the couch." His practice differed, therefore, from institutional critiques that focus on the backstage machinations informing aesthetic experience in galleries or museums. McCollum did, too, but fixed on the foreground as an arena for any viewer's experience in front of any cherished item across diverse venues. This encounter is conditioned, albeit, by all the stuff in the background—including how ideas about art inflect our relationship to other valued collectables.

Playful and nightmarish, the exaggerated presentation of the Surrogates underscores the heightened artifice involved. So does the fact that McCollum frequently referred to his pictures as "signs" for paintings and to their installation as a "dramatization" of the viewing process. Foregrounding the conventions of painting and display, the exhibitions dramatized the circumstances and attitudes influencing art's reception. Theatricality was perhaps most evident in McCollum's description of the artworks as "props."[3] That term is abbreviated from "theatrical property," meaning an object used for significant effects within a performance-the way his works operate in the Surrogate installations. Yet it evokes a prop in the ordinary sense, one that shores up and supports something else. It seems only appropriate, then, that the artist would produce his own props, or "supplements"—objects, texts, and events that accompany and frame his art.[4]

McCollum's supplements, the topic of this essay, have become increasingly primary in his recent endeavors. Small sculptures he refers to as "souvenirs" or sheaths of didactic writings, they are exhibited alongside the artworks they ostensibly support. This auxiliary material has expanded to the point of overtaking, materially and conceptually, the works of art on view. In some ways, it has become a surrogate for the art, which was a substitute or proxy to begin with. One effect is to cast the art—and, paradoxically, not its supplements—in an even more subordinate position. But this dynamic was already nascent in McCollum's earlier practice.

Some of the first supplements were appendages to the Plaster Surrogates, designated sidekicks called Surrogates on Location, Incidental to the Action (1982). These are "installation views" of an entirely different order. McCollum re-photographed scenes from mass media, both fictional and documentary, when they contained artworks resembling his Surrogate paintings. The art within the appropriated pictures is located physically and qualitatively in the background (a state emphasized by dramatic action in the foreground). The actual distance effaced the image, making it appear identical to one of McCollum's blank Surrogates. The photographs show art or art-like objects circulating in the culture at large, mostly as ubiquitous props lurking in the margins of virtually any interior. The Surrogates on Location did not circulate, however, in ways typical of fine art. Exhibited only in secondary peripheral spaces—a gallery's foyer, hallway, or office—McCollum's ancillary pictures did not share equal billing with those in the exhibition space. This was enhanced by the fact that they were not for sale, withdrawing exchange and exhibition values that prop up aesthetic evaluation. McCollum's photographs took a supporting role, just as the art pictured within them did. While his art equally fixes on our extreme emotional investment in certain objects (such as the overabundance of value accorded fine art), these images show art functioning in daily life—as decorative embellishment, incidental things attended to occasionally. The Surrogates on Location imply that art supplements events more significant than any concrete thing. Later work explicitly maps the relationship between surrogates, supplements, and events.

Event

Beginning in the late 1980s, McCollum's practice shifted. Retaining his trademark interest in surplus quantities and multiple copies, he turned to naturally occurring reproductions-fossilized objects and the events that precipitated them. The resulting works include Lost Objects (1991) and The Dog from Pompei (1991), as well as two later works, Natural Copies from the Coal Mines of Central Utah (1994/95), cast dinosaur tracks painted in colorful hues, and THE EVENT: Petrified Lightning from Central Florida (with Supplemental Didactics) (1997). A natural cast called a "fulgurite," petrified lightning is created when lightning strikes sand that melts and hardens to create an exact replica, in glass, of its underground path. For THE EVENT, the artist made a mold from a fulgurite and cast 10,000 multiples in sand and epoxy resin. To say that the fulgurite McCollum chose was a found object or readymade is to use a misnomer. He "assisted" in its creation, shooting a rocket into the sky to induce a lightning strike directed at a container on the ground (filled with a specific type of sand effecting its shape). Both the original object and McCollum's copies are the byproducts of a process, extant traces of earlier phenomena. Here, too, we can find a precedent in the Surrogates. The art exhibition—a singular temporary occurrence—is recorded in photographic documents. Prompted by these black-and-white images, McCollum started painting the Surrogates' frames in shades of gray to replicate their appearance in the installation shots. Hence, the exhibition might be experienced as if walking through the photograph that would later record it. One show's title, Installation View, highlighted the photographic origin of their "gray scale" and the fact that the installation and its record were intrinsic to the art's reception. Moreover, it emphasized how the art or exhibition was frequently experienced: secondhand, through a surrogate or proxy. Fossil records share this condition as artifacts memorializing something definitively past, although they embody natural rather than social history. But McCollum immediately reinstated a cultural component.

He began to explore a particular kind of event, the meaning and use of these natural objects for communities near the sites where they were discovered. McCollum's related art projects were subsequently exhibited in local historical societies and natural history museums in the surrounding areas. Viewers included residents of small towns where the fossils were found and embraced as totemic signs within their communities. The artist noted that hotels and restaurants near Dinosaur National Monument in Vernal, Utah, often include the word "dinosaur" in their names. Similarly site-specific, frequent lightning strikes are common to Florida, known as the lightning capital of North America—a dubious distinction absent from its tourist brochures. While broadening the consumers for his art, McCollum expanded its producers, collaborating with scientists at the International Center for Lightning Research and Testing in Starke, Florida, and local industries (Sand Creations, a Florida factory specializing in mass-produced tourist souvenirs that cast his fulgurites[5]). The work still spoke to symbolic objects as manifestations of some past action or set of calcified relations. Yet now it implied that art might be a catalyst, forging new connections with unanticipated audiences or collaborators.

Fossilized dinosaur footprints are excavated during mining operations, a byproduct of local industry. They are frequently displayed in miners' front yards or donated to regional museums. Moving beyond the insular world of fine art, McCollum did not abandon allusions to it, including 1960s process and task-based art. Indeed, he characterized the tracks' excavation as evocative of a master narrative for common cultural myths about artistic practice. The artist likened the story of miners digging out the tracks "to the idea of going down deep into the unconscious and pulling some artistic inspiration from you do not know where."[6] The fulgurites offer another parable for creativity. The lighting strike connotes a spontaneous event happening, as McCollum put it, "from above and out of the blue."[7] This allegory of instantaneous insight differs from the story about buried treasure painstakingly retrieved. Yet both aggrandize the creative process, as ethereally luminous or profoundly deep, epiphany or belabored revelation. Although the small gray fulgurites are an unassuming deposit, contradicting lightning's spectacular beauty, in his experimentation, McCollum created a squiggly one that happened to resemble a painter's brushstroke. Like the fulgurites, the unearthed tracks are mostly geological curiosities, scientifically inconsequential. Having value only in situ, the footprints' pathway explains the dinosaur's size, movement, or behavior by its gait—a use lost when decontextualized. Nonetheless, the tracks and fulgurites incarnate their formative event, the trajectory of dinosaurs or of lightning, in an indexical snapshot, They are permanent surrogates for a moment and movement, petrified in stone or glass. But McCollum supplemented his fossil casts with something more ephemeral—written statements about the objects and the circumstances that produced them.

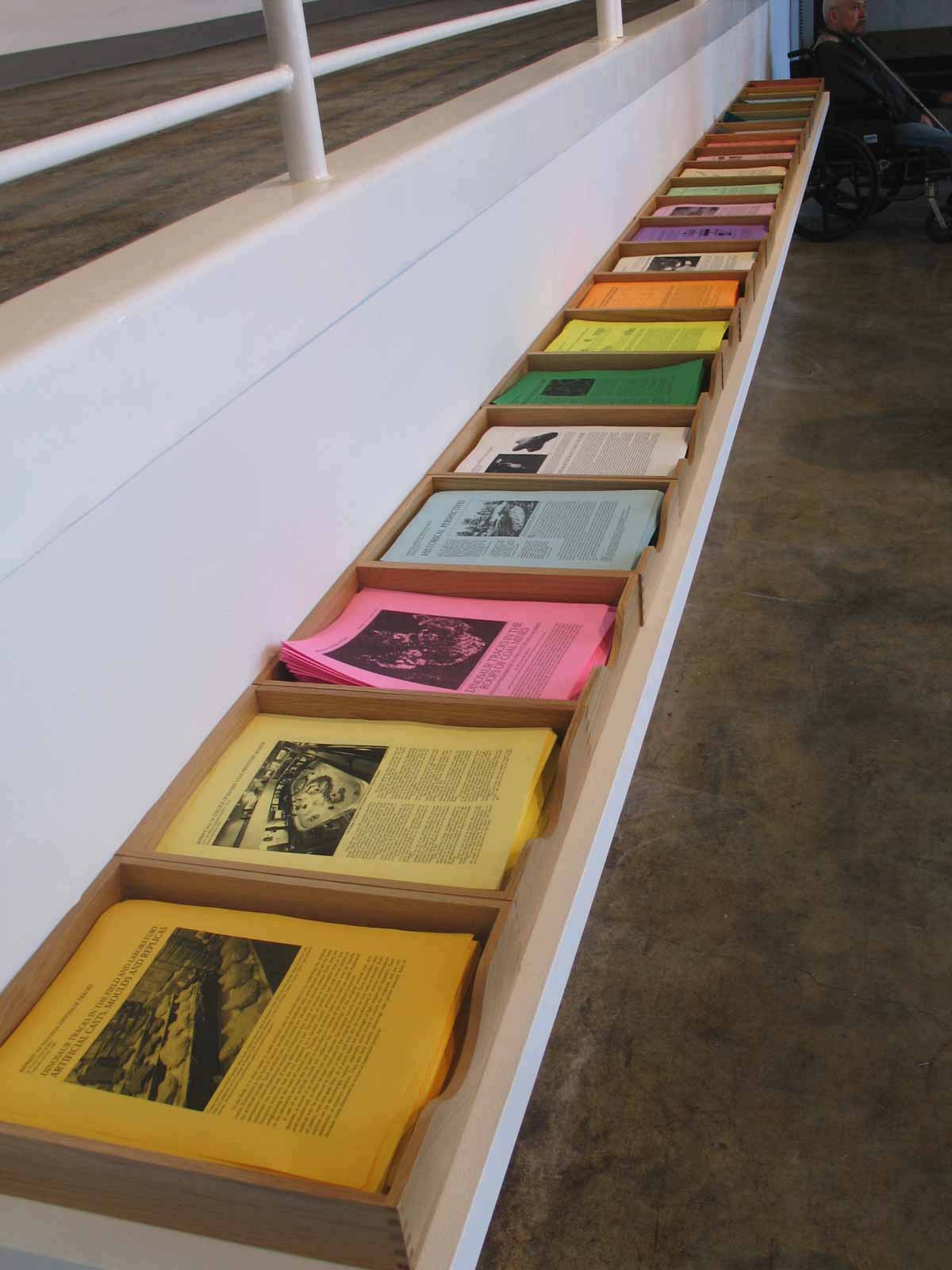

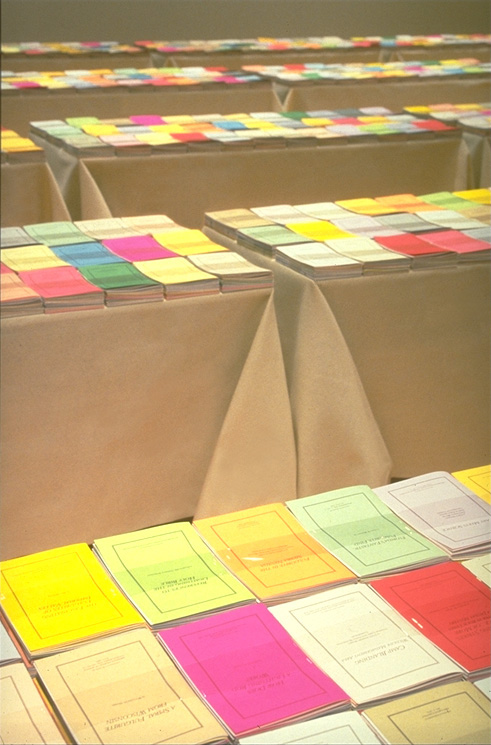

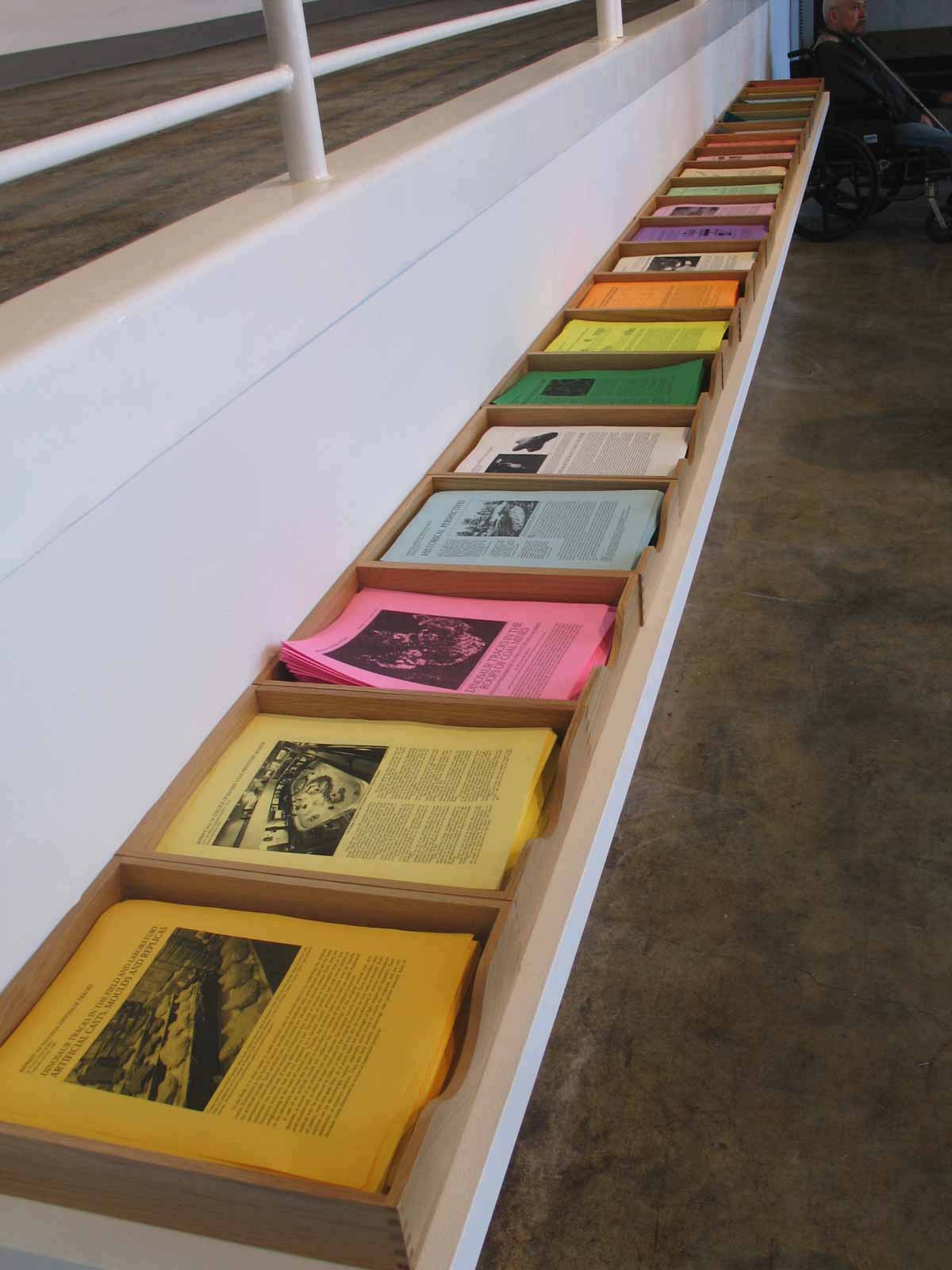

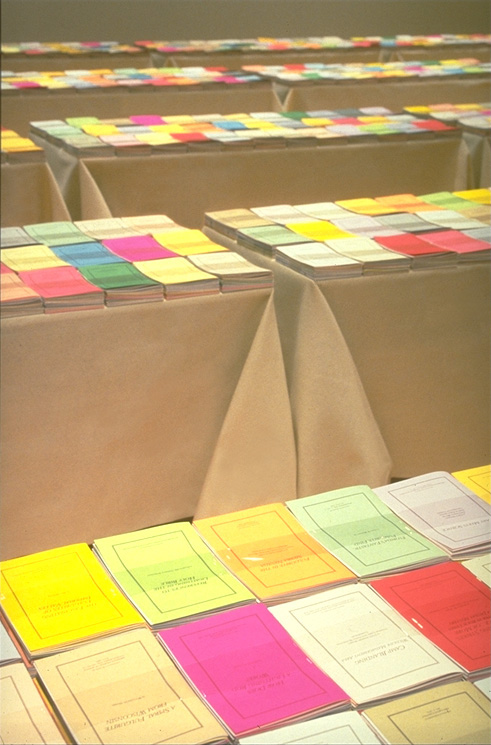

The cast dinosaur tracks of Natural Copies from the Coal Mines of Central Utah come with Reprints (1994/95), related didactic articles, while THE EVENT: Petrified Lightning from Central Florida (with Supplemental Didactics) includes, as the title indicates, its own expository narratives. The adjunct material for both takes the form of brief explanatory texts exhibited in stacks on tables next to the tables of artworks. Twenty-one Reprints were available in hundreds of photocopied handouts; sixty-six Supplemental Didactics were presented in over 13,000 brightly colored booklets, their number dwarfing the quantity of adjacent sculptures. Each set of commentary, whether about dinosaurs and their fossilized tracks or lightning and its petrified trace, is by an assortment of authors offering different perspectives on these subjects. Ranging from scientific to mystical, Darwinian to biblical, most of the writings are wholly extrinsic to fine art, yet their titles ironically conjure it up. They seem to reference McCollum's work and its production modes, such as "Dinosaur Tracks in the Field and Laboratory: Artificial Casts, Moulds and Replicas"; or art in general, as in "Elite Tracks," "Identifying the Track-Maker," and "It Can Be Difficult to Determine the Exact Boundaries of a Footprint." Practical and poetic, the fulgurite tracts include "How Many People Are Killed by Lightning Each Year?"; "References to Lightning in the Holy Bible"; and "Sudden Illuminations, Like Lightning," by Wassily Kandinsky. The texts have other uses. Source material, they comprise the artist's research, influencing each project's conception. In turn, all of the information is currently available on elaborate websites McCollum designed for educational purposes regarding the fossils in general. On the other hand, the didactics serve as meta-commentary for the varied responses that any cathected object elicits—one for each spectator carting their own concerns, baggage, or background to the viewing process. These will inevitably diverge and conflict, producing no singular definitive reading. Yet they might overlap at junctures touching and uncanny.

In Between

When McCollum exhibits his art in regional science and history museums, he affiliates fine-art institutions with non-art venues. The fossil projects also make analogies between art and other objects or art installations and other presentation formats. Splayed across tables, his sculptures and their supplements recall specimens in a scientific display, factory showroom, or trade fair. The Surrogate shows had similarly alluded to commercial installations, poster or frame shops, and personal displays of items with significance such as diplomas in the office or family photographs in the home. The fossil-based work wandered further afield from fine art proper. Two more recent works again segued between multiple frames of reference—past and present, nature and culture, geography and politics. For Signs of the Imperial Valley: Sand Spikes from Mount Signal (2000-01), McCollum chose an object from the collection of a regional museum. Formed over thousands of years, sand spikes are fossil-like concretions found at the base of Mount Signal, which straddles the border between the State of California, in the United States, and Baja California, in Mexico. The artist made large-scale sculptures of one of the museum's spikes and the mountain itself. Other sculptures, created as souvenirs, were intended for exhibition as well as for sale in museum gift shops: replicas of the sand spike and small plaster models of Mount Signal, over one thousand of each. Between 2000 and 2001, all were displayed, along with didactic texts, at four venues in the United States and Mexico: the Imperial Valley Historical Society Pioneers' Museum in Imperial, California; the Museo Universitario, Universidad Autonoma de Baja California in Mexicali; the Steppling Art Gallery at San Diego State University's Imperial Valley campus in Calexico, California; and the University Art Gallery at San Diego State University's San Diego campus. Since the mountain sits on the United States/Mexico border, the accompanying texts appeared in both Spanish and English. An emblem throughout the surrounding communities, the mountain is ubiquitous in local artists' paintings, drawings, and photographs; government documents and regional business logos; and poems and tourist postcards. Over sixty examples of works created by local artists and dozens of examples of local memorabilia items incorporating the mountain's image were included in the exhibition. The idea of differing perspectives on a particular object, symbolic for the region's various inhabitants, was made literal in the array of items on view, as was the diverse sense of individual or group identity congealed in a single entity.

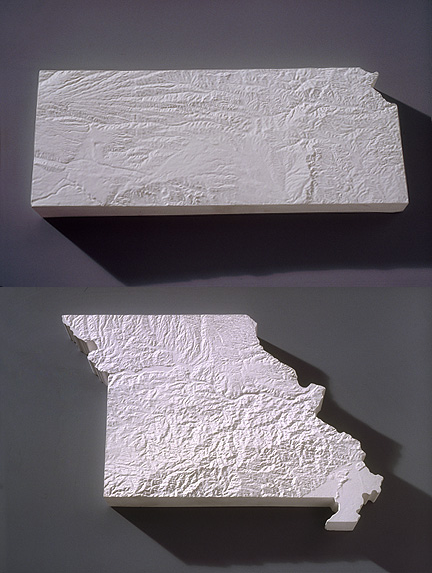

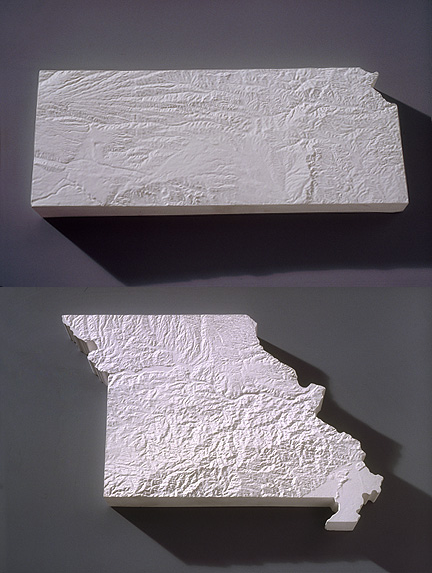

Another endeavor, The Kansas and Missouri Topographical Model Donation Project (2003), consists, like the models of Mount Signal, of relief models based on satellite data of the area's topography. Here again, communal identity is tied to geographic and social phenomena, joint forces producing a map's boundaries. McCollum envisioned the project, however, in two versions: twelve in glazed ceramic, a refined media associated with valuable decorative objects, and 120 in unfinished HydroStone (to be painted as the recipient wishes), a material affiliated with novelty items and statuary. Commissioned by Grand Arts Gallery in Kansas City, McCollum proposed a bifurcated scheme for funding and distribution as well. The grant money would be used for unique artworks, the ceramics, exhibited and sold in the gallery; and for others, the plaster multiples, donated to 120 small historical societies throughout the two states. In his mind, he said, the works for local museums took precedent over the ones designed for fine-art institutions, making the "legitimate" works of art supplemental to the donated ones. Those intended for state museums would be ensconced among a variety of objects pertaining to the area. Traveling to each regional institution, McCollum donated the works in person, this "event" being central to the piece.[8]

More

Supplements are a parergon, in Jacques Derrida's sense of the term.[9] Framing something, they are at once inside and out. The frame is an apt figure, too, for McCollum's sense of high art as inclusive and exclusive. It can distinguish the few, those who access or control ownership, distribution, aesthetic discourse, and the canon (determining who's written in or out of history). For McCollum, this poses questions about taste and class. He has always conceived of fine art, among its other uses, as reifying social hierarchies. Speaking of his own working-class background, he noted: "Museums are filled with objects that are commissioned by, or owned by, a privileged class of people who have assumed and presumed that these objects were important to the culture at large... My awareness of [who] decide[s] what goes into these shrines, and how we are expected to emulate their tastes in our own lives, and find personal meaning for ourselves in their souvenirs ... becomes the major factor in my experience of being in a museum."[10]

This attitude is reflected in his embrace of multiple copies and surplus quantities—as opposed to the rare or unique—whether mass-produced industrially or through nature's fecundity. If a frame is both encompassing and exclusionary, what it encloses can reward or torment as well. When McCollum likened his Over Ten Thousand Individual Works (1987) to Melanie Klein's concept of "the nurturing and persecuting object" (the art object, the mother's breast), he suggested the conflicted response such objects inspire.[11] The Individual Works' sculptural elements consist of various parts combined so that no two are alike. These were cast from ordinary things—bottle caps, baby pacifiers, contact-lens cases—created by anonymous designers. The artist conceived of each Individual Work as a unique symbol for each singular viewer.[12] The items depend on being seen in relation to one another, their similarities and differences noted. Utopian and nihilistic, the staggering quantity is comforting—conveying plentitude, abundance, or unity—and alienating, each one anonymously lost in a sea of all the rest.

McCollum consistently imagines a range of audiences and their varied expectations of art or other relics, high and low, and his work continues to explore the ways valued objects concretely manifest social relations. But the recent projects offer a different object lesson, Although the blank Surrogates have typically been described as placeholders (empty generic signs for any picture), the later work implies that they, like it, are empty vehicles of another sort. The art still appears as the product of, and cipher for, prior events or discourses. And the didactics provide a history of opinions regarding the objects upon which McCollum's artworks are based. Made available within the exhibition or on the Internet, one might access them even before encountering the art to which they, by extension, refer. A necessary appendage, they prop it up in advance. But the written material suggests that art awaits a later event—the moment when, made public, it will be filled or fulfilled by viewers' associations and projections. Regarding his sand spikes, the artist asked, "Maybe The Meaning Of An Artwork Is The Sum Of All Meanings Given To It By The Sum Of Its Viewers?"[13] Imposed from outside yet conjured up by things internal to the work, the accumulating reception becomes integral to it. A concretion continually built up, each new deposit is embedded within it.

Yet might this sum of interpretations unite audiences rather than dividing them, as McCollum had previously conceived of the artwork? With art mediating between social groups, these exchanges could just as well entail interrelated communities and shared horizons, analogous values or histories. The utopian bent of his recent efforts is evident, as well, in the inclusiveness of his supplementary objects (one for everyone) and multiplicity of supplemental texts (where anyone's take, on a given object, is taken into account). The didactic essays invoke a particular kind of surplus: that of an object overdetermined, in the Marxist or Freudian sense. Encyclopedic, they offer a spectrum of views on a single item, freighted with meanings and affect. The artist's ongoing concern with surplus can be read through his interest in surrogates and supplements. For the surrogate is surplus, a replacement or extra copy; likewise, the supplement, as additional backup (compensating for some deficit in the thing itself). Both are conceptually or chronologically secondary to the main event or object—an aftermath formed in its wake, an expendable trace leftover and overlooked. McCollum inverts this logic. The supplement gets brought to the forefront, the crucial stage prop that alters the storyline or sets a whole new course of events in motion.

Footnotes

[1.] Bertolt Brecht, Brecht on Theatre: The Development of Aesthetic, ed. and trans. John WiIIett (New York: HiII and Wang, 1964), 194.

[2.] Allan McCollum in D. A. Robbins, "An Interview with Allan McCollum," Arts Magazine (October 1985): 41.

[3.] In addition to the terms "sign" and "dramatization," McCollum has repeatedly used the word "prop" in interviews. See, for example," Allan McCollum interviewed by Thomas Lawson"(1992), in Allan McCollum (Los Angeles: A.R.T. Press, 1996), 2. McCollum also noted that he was at the time aware of a 1967 piece Paris-based artist group BMPT (composed of Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Daniel Parmentier, and Niele Toroni) that thematized the theatrical nature of the art exhibition. For this work, each artist placed one their paintings on a proscenium stage and, with the audience assembled, pulled back the curtain for one hour of viewing.

[4.] Obviously, precedents exist for supplementary material incorporated within—or functioning as—a work of art, particularly in 1960s Conceptual practices. While the "supplement" recalls Jacques Derrida's discussion of that trope—just as the "surrogate" resonates with Jean Baudrillard's notion of the simulacrum—McCollum claims not to have been influenced by either. These two models inform my reading of the work, but his touchstone has always been structural anthropology.

[5.] For analysis of McCollum's fulgurite project, especially in relation to the concept of the souvenir, see Helen Molesworth, "Impossible Objects: Man-Made Fulgurites by Allan McCollum," Documents, no. 17 (Winter/Spring 2000): 40-49.

[6.] See Catherine Quéloz, "Restoring the Cases Required Nearly as Much Work as Preserving the Artifacts, Documents sur l'art (Dijon, France) 8 (March 1996): 59-60. See also Quéloz, "Interviews with Allan McCollum (1995/2008)," in Allan McCollum, published by JRP|Ringier, 2012.

[7.] Jade Dellinger, "Interview with Allan McCollum," in THE EVENT: A Project by Allan McCollum (Tampa, Florida: Contemporary Art Museum, University of South Florida the Hillsborough County Museum of Science and Industry, 1998), n.p., available at: http://www.allanmccollum.net/allanmcnyc/dellinger_mccollum.html

[8.] Giving art away potlatch-style is part of McCollum's Visible Markers (1997), small colorful scuptures resembling Fort Knox gold bars inscribed with the word "Thanks." Each acquires meaning—like a semiotic shifter—only when "in use" by a specific person (gifted by the collector as a token of appreciation).

[9.] See Jacques Derrida, The Truth in Painting, trans. Geoff Bennington and Ian McLeod (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987).

[10.] McCollum, in Gray Watson, "Allan McCollum," Artscribe International 55 (December/January 1985-86): 66.

[11.] McCollum, in "Interview with Allan McCollum," 44.

[12.] McCollum's The Shapes Project (2005-ongoing) made this aspiration literal, potentially creating one emblem for each person on the planet.

[13.] McCollum, introduction to Signs of the Imperial Valley: Sand Spikes from Mount Signal (1995-2001), 2000, available at http://allanmccollum.net/amcimages/introduction.html.

|

|

View of Surrogate Paintings (1978/81), installed in McCollum's studio, New York, 1981

Surrogates on Location, Incidental to the Action, 1982/84.

Copy print, 8 x 10 inches

Surrogates on Location, Incidental to the Action, 1982/84. Copy prints, 8 x 10 inches each. Installation at Kohji Ogura Gallery, Nagoya, Japan, 1993

Lost Objects, 1991. Enamel on glass-fiber-reinforced concrete. Cast dinosaur bones produced in collaboration with the Carnegie Museum of Natural History and the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Installation: John Weber Gallery, New York, 1992.

The Dog from Pompei, 1991. Cast glass-fiber-reinforced Hydrocal, 21 x 21 x 21 inches each. Installation in The Dog from Pompei, Galeria Weber, Alexander y Cobo, Madrid, 1992.

The Dog from Pompei, 1991. Cast glass-fiber-reinforced Hydrocal, 21 x 21 x 21 inches each. Installation in The Dog from Pompei, Galeria Weber, Alexander y Cobo, Madrid, 1992.

Natural Copies from the Coal Mines of Central Utah, 1994-95. Enamel paint on cast polymer-enhanced Hydrocal. Natural dinosaur track cast replicas produced in collaboration with the College of Eastern Utah Prehistoric Museum, Price, Carbon County, Utah.

Natural Copies from the Coal Mines of Central Utah, 1994-95. Enamel paint on cast polymer-enhanced Hydrocal. Natural dinosaur track cast replicas produced in collaboration with the College of Eastern Utah Prehistoric Museum, Price, Carbon County, Utah.

Reprints, 1994/95. Twenty-one handouts on the topic of natural casts of dinosaur tracks, researched and edited by McCollum and available to visitors of Natural Copies from the Coal Mines of Central Utah, 1994/95

THE EVENT: Petrified Lightning from Central Florida (with Supplemental Didactics), 1997. Epoxy and zircon sand replicas and texts. Over 10,000 replicas: approximately 8 x 1 inches each, Produced in collaboration with Sand Creations, Sanford, Florida; International Center for Lightning Research and Testing, Starke, Florida; Contemporary Art Museum, University of South Florida, Tampa; and Hillsborough County Museum of Science and Industry, Tampa. Installation at Friedrich Petzel Gallery, New York, 2000

Selection of the 13,000 copies of 66 booklets produced as part of THE EVENT: Petrified Lightning from Central Florida (with Supplemental Didactics), 1997. Installation at the Contemporary Art Museum, University of South Florida, Tampa

Topographical Models of the States of Kansas and Missouri, 2003. Cast in Hydrostone, painted with enamel. On the walls: silhouette drawings of all the counties of Kansas and Missouri. Installation: Grand Arts, Kansas City, Missouri.

Topolographical model of the state of Kansas, approximately 4 x 11 x 27 inches, made from fiber-reinforced cast plaster, coated with white primer; topographical model of the state of Missouri, approximately 3 x 23 x 17 inches, made from fiber-reinforced cast plaster, coated with white primer. McCollum drove throughout the two states, and donated the models in person to 120 small historical society museums, to use as they wished.

The Kansas and Missouri Topographical Model Donation Project, 2003. Hydro-Stone model painted by the Oakley High School Art IV class for the Fick Fossil and History Museum, Oakley, Kansas, 2003

Over Ten Thousand Individual Works (1987) packed in boxes in McCollum's studio, New York, 1987

Over Ten Thousand Individual Works, 1987. Acrylic paint on cast Hydrocal. Between 2 x 3 and 2 x 5 inches each. Installation in Allan McCollum, Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 1989.

|