|

May I Help You? 1991 |

| ANDREA FRASER |

Seated behind a desk along the south wall of the exhibition space are three performers who constitute "The Staff." They are "busy" with what looks like gallery business hidden behind a low, white, plaster-board wall. A visitor enters the gallery and makes her way to the center of the exhibition space. As the visitor begins to look at the exhibition, one member of The Staff gets up, walks over and begins to speak. 1. The Staff member's manner is gracious and unconcerned. She is self-assured, authoritative but unthreatening. She is ease and sureness. Her posture and bearing are "perfect." She draws out and lingers over her vowels. (Her manner changes over the course of the performance.) The Staff member approaches the visitor.It's a beautiful show, isn't it. And this . . . She walks over to one of the Plaster Surrogates.. . . is a beautiful piece. She pauses for a moment, looking.I would say that this work is the apotheosis of abstraction. It's an abstraction that implies an absolute simplification and reduction within a language of well balanced purity. It has extraordinary colors and formal intensity. The first time I saw it I fell in love with it. It's a radiant work—and one of the most original. It's one of a kind. A sophisticated composition of austere dignity. It's sublime—almost transcendent. It's distinctive, disinterested, gratuitous, refined, restrained, sober, calm, guileless, good, simple, certain. It's perfect. It has such tact, such grace, such quiet self-assurance. It's . . . She pauses again, then moves closer to the work. She looks at it for a moment. As she looks her expression becomes increasingly peaceful as if, in looking, all of her wants are satisfied.. . . so far away from the passions that ordinary people invest in their ordinary lives. This is art. This is culture. She turns back to the visitor, looking far away at first. Now there's a hint of sadness in her expression, a hint of loss. She brings the visitor back into focus then slowly looks her up and down, without moving her head. She looks into the visitors eyes for a moment with a blank expression, then smiles. She continues with the same manner as before, only now addressing the visitor as someone known to her.It belongs to a more polite society, a more polished, better placed world of bearing and harmony: the total, beautiful environment of an ultimate life of appreciation on the highest level of response. It's the expression of a fully developed taste—the taste that allows you to give such coherence to your collection. She moves to another Plaster Surrogate.

You know, what counts for me, first of all, is the beauty of the thing. The value isn't what counts. It's the pleasure that it gives you. My favorite clients have always been the ones who collect out of love, just as children collect postage stamps. You fall in love with a thing that pleases you and you can't resist it. I always prefer pleasure. Pleasant things are non-necessary things. That's our inheritance. Freedom from the lower, coarse, vulgar, servile, material, demands of the social world. She gestures toward the Plaster Surrogate.Look! It's the illusion, first of all, that it hasn't been made, that the plaster and paint were never produced and mixed and cast and applied, coat after coat, by a studio of labor. It's the illusion that none of this was paid for and nothing will be bought, and it hangs there as if it just spread itself out before us voluntarily, of it's own volition. It has always been there and will always be there—for us. The only work you do is wanting: I want it and I have it. It's as simple as that. And then you produce it's value—an inward value, an emotional value—when you've wanted it, you've looked for it and, at last, you've found it. And you would do anything to have it. You want it more than your mother's love—more than money. You have to buy with your eyes, not your ears. You really buy with your soul. 2. The manner of The Staff member changes slightly. It becomes less formal, softened by a familiarity extended to the objects as well as the visitor. With a gesture toward the visitor to follow her, she walks toward the rear of the exhibition space.I always tell my clients that the criterion for buying an artwork should be whether you would want it in your home. Loving something means having it with you. Your collection expresses the texture and quality and even the smell of your life. It permeates everything about you, from the condition of your teeth to the way that you love. You're branded by the objects you love. They mark you as the property of your culture, the property of your class. Abruptly, she turns to an object.Now, imagine this picture tattooed on my shoulder. She turns back to the visitor, unfolding her arms in an elegant, graceful gesture, elaborating her body rather than the words she speaks.It's like that. Imagine the clothes that I'm wearing and the rest of my environment have been painted on my skin and then the whole thing is turned inside out so that it's the stuff inside—the shoes, the sofa, the dining room. You know, these are the things for which you'll be remembered. These are the things for which you'll be loved. It's always with you. It's inside. And it's outside, at the same time, for everyone to see. It's a prison. She suddenly becomes transfixed by something she sees over the visitor's shoulder (but isn't really there). She draws a breath sharply.Oh! Look at that. She gestures along a wall.At certain times of day, the way the light floods in through these windows . . . Stunning! It's a wonderful space. She leads the visitor to another Plaster SurrogateI was born into a world of art. My mother, you know, was an extremely cultured and sensitive woman. All her life she was an attractive, simple worshiper of what everyone knows is the best: the best society, the best individuals, the best standards of living with all its appurtenances. When I go to a museum, like the Metropolitan, I feel right at home. She gestures around the gallery.That's how my mother hung her collection—but in the foyer, the dining room, the living room, the bed rooms, the guest rooms, the halls, in the bathrooms . . . Turning toward a Plaster Surrogate.She had one of these in the bath. Turning again to look around the gallery.It's a wonderful house. Quiet, calm and cool, like fresh linen laid in wicker trays, with something beautiful in every corner, flowers, and the freshest smell. She inhales deeply then turns back to the object, gesturing toward it's blank, black center.That's my Grandmother there. She was beautiful. And that's me. She straightens the Plaster Surrogate, touches the top of it, looks quickly at her hand for traces of dust, turns around, frowning, then looks to the front of the gallery and to the back for the person responsible. She leans toward the visitor.You know, some people come in here and they want to invest and then they haven't got the time. Imagine! They haven't got the time to be personally interested. On the one hand investment and on the other, total incompetence. If you stuck a piece of shit on the wall it would be all the same to them as long as someone told them the shit was worth money. That's the nouveau-riche approach. Pork bellies. And I detest souvenirs. Oh, I've bought little knick-knacks and trinkets that I've distributed to all and sundry, but I'd never clutter myself up. She turns around suddenly. Projecting her voice across the gallery, toward the door to the street.May we have some quiet in here, please! She moves back toward the visitor.You'd think that there was a mob of people, pushing. I hate crowds, filling the air with their breathing and their noise. For example, suburban secretaries who fill their gardens with gnomes, windmills and similar rubbish. Mummy used to say, "It's outrageous. Making things like that ought to be banned. Horrible. Horrible habits. They don't even know how to eat, those people, heavy, thick, bloated and fat with hunger on cheap foods." She stops and steps back from the visitor.Well, I suppose I always spoke up for everyone's right to have their own taste. Why not? At least they have . . . a taste! 3. The formality and restraint that have marked the performance thus far disappear from The Staff member's manner. She begins to bring her body into her relationship with the objects. The poise and self-assurance that remain now have the aspect of defiance and dismissal. They are things to be displayed.I think it's charming! She turns sharply to address another Plaster Surrogate. She gestures toward it with her shoulders and head as well as her arms.It's so simple and fervent, so direct, so real. Sturdy, happy, uncomplicated: leave it unspoiled and just enjoy it. That's what I always say. My mother, you know, was just an attractive, simple worshiper of what everyone thinks is the best. She wasted her life on linen and flowers. It was an empty, empty, airless, dusty, meaningless life. Suffocating. Sumptuous and boring. Heirlooms? Don't make me laugh. I just can't bear the gentility of some galleries and museums. There's just so much work around now that I find completely grim. It doesn't appeal to me. I can't be bothered with it. I think it's complete tripe. And I hate people who are producing neat, tidy work. I just don't like eggs. Gesturing around the gallery with enthusiasm.Now this is an artist who's doing exactly what she wants. It's a breath of fresh air! I asked her once what attracted her to this subject and she said, "It just interests me, it's what I want to do." She has the capacity to surprise me on a regular basis. Sometimes she's here and I offer her coffee and I get the feeling that the cup isn't clean enough for her and then the next thing I hear she's off in Africa somewhere—rolling in the mud. Have you been to Africa? Moving to another Plaster Surrogate.

She's the real thing! She's still out there—she's really out there. And she puts everything into her work. It's the shirt on her back. It's her neighborhood bar. It's the songs her mother sang to her when she was a child. It's the man she loves. It's her life. And it's not expensive! Not expensive! It's incredible. It's a woman in a bikini at a cocktail party, it's so outrageous. Everyone thinks it's outrageous—except me, of course. I think it's funny. And it's sexy. And it's one of the ugliest smears of paint I have ever seen. It's the top. It's a Waldorf Salad. What do you think? I think I must have been born with a love of the unfamiliar. It's something you can't be taught. And I'm happiest with works of my time. They reflect me. 4. The Staff member's manner changes. It becomes less poised and more businesslike. Her speech becomes more direct and pragmatic. She shortens her vowels and sharpens her consonants, emphasizing each word in each sentence. She becomes more outwardly engaged. She extends to the objects and the visitor the kind of earnest and thoughtful enthusiasm with which she might approach a problem to be solved‑a problem with which she foresees no serious difficulty.My favorite clients have always been the ones who try to be out on the edge, even if they have unlimited resources—and most of them don't. It's better to be buying artists who search out new directions, to be in the forefront with them. By the time it gets into the museums and the auctions, it's safe. There's no discovery. Hey, where I grew up there was no art. There were a few family things, pictures passed on. There was no culture. I'm the first in my family to go to college—almost. I had to leave them behind. This wouldn't mean a thing to them. Except that I'm a success. It just shows you how narrow their lives are. I've always wanted art to question what I know already, to open me up as a human being so that my life is more deeply significant. A Plaster Surrogate attracts her attention. She turns to it to support her point.Now this is a piece that I find extremely challenging, okay. This is a work that no one without our precise history and educational background could possibly fathom. Can you believe there are still people asking that tired old question, is it art? Right? This is about process. This is about procedure. It's too easy to say, It's in a gallery. You know, she's really an intellectual: self-possessed, reflexive. And in this work she's forcing the viewer to be reflexive too. She pauses for a moment to reflect on the work. She looks at it, nodding her head slightly. She turns to the visitor, still nodding, then back to the work.It's a very risky work. It's critical. That's the kind of work she dares to do. She's never made a safe decision in her life. She doesn't know how to. And that's terrific. You know, for a long time she didn't even make anything to sell. She turns away from the work.It's so far away from the rational, quantitative world of business and finance. But just like in business, you have to take risks if you want an edge. Art keeps your mind limber. I always prefer risk: creating, building, inventing, investing in visions of change and opportunity. Hey, I was having lunch with David Rockefeller the other day at the Modern, and David said to me, he said . . . For a moment she takes on the voice and manner of The Staff member during first section of the performance."Andrea, there's just no place for you on the board. Go back to the Now Museum or wherever it is you—" Imagine! That's what I want. Old money. That's not culture. That's blood. 5. The Staff member's manner changes. She becomes uneasy with her body and her speech. She checks and corrects herself, as if she's watching herself through the visitor's eyes.Oh, where I grew up there was no art. There was no culture. We lived on the edge of the rich part of town. They really hated us. I'd never bring friends over. There were always buttons missing on my mother's dress. Looking around the exhibition space.I went to museums and galleries to see what it would be like to live in a big, clean, quiet house. She absently looks at the visitor's shoes.I learned just from looking. She picks up her head and smiles.I always wanted to be a beautiful person. She turns to address a Plaster Surrogate. While she talks about the object she continues to smile, displaying the pleasure she takes in the work.It's interesting isn't it. It's abstract. It's sort of simplified, reduced in a way, maybe, purified. She looks at the visitor's clothes.But it's aesthetically beautiful because of the colors and the formal relationships. I like it. It has a kind of presence. It's original. And it's obviously very sophisticated. It's, it's almost... She turns back to the object.It's almost... She looks intently at the object. She looks to buy time to find the right words to describe it; to adjust herself, her shirt, her hair. She looks to the visitor then back to the object almost as if she's checking herself in the mirror. As she turns to the visitor one last time her smile fades into an expression of defeat. She turns back to the Plaster Surrogate and continues, speaking to herself now, instead of the visitor.Oh, I don't know how to put it. Is it . . . Is it the subject or the technique? What do you think? 6. The Staff's manner changes. Defeat becomes weariness and fatigue. She drops her hands and clasps them loosely in front of her. She speaks casually and confidently as if to someone in her home, as if she has paused while clearing coffee cups to the kitchen.It's pretty, isn't it? It's nice. It's cheerful. Maybe it's a silly picture for me to like. I stop everyday, once or twice, and look at it, and somehow, I feel better. Don't ask me why. I'll be tired and I'll be sitting on a chair with my head down nearly to the floor, and I look up and there it is. I don't claim to be competent. I like art, but I don't know very many artists' names. I'd like to, but I haven't got the time. It's always the same, you've got to have the time. She becomes more animated.I've got a lot of trinkets and odds and ends that I found in aunts' and uncles' attics. They were terribly tarnished and rusty but I cleaned them up. All those things are worth a bit now they're cleaned up. She gestures around the exhibition space. This place is no museum, but the vases aren't dust-traps either. They all have their use. She points to a Plaster Surrogate and walks toward it.That vase now. I needed a vase because I wanted flowers, and when they asked me what I wanted, I said, "a vase." And they bought it for me because I know how to make good use out of it. She pulls a small handkerchief out of her sleeve. She unfolds and refolds it, then dusts the Plaster Surrogate while she talks.They know very well not to buy me things I won't use. I don't have money to throw away. I don't agree when they say, "you should get something you like." You often have to do things in life that you don't like to start with, but you just have to like them. She puts the handkerchief back in her sleeve and looks at the Plaster Surrogate for a moment.My mother liked to keep things clean. Turning to the visitor.My mother would dust and sometimes help cook, though it wasn't her job to cook. There was another woman there whose job it was to cook. My mother would come home and describe their house. A lot of pictures, fresh linen and flowers. She passed away, my mother. A slow death in a terrible, small room. 7. The Staff member's manner changes slightly once more. She speaks now in the space of the gallery and to a stranger, with the casual confidence about things that are, for her, commonplace. She turns back to the same Plaster Surrogate.Maybe this is a fine piece of art, but it's not for me. I wouldn't know what to do with it. This is the kind of thing that only means something to a particular type of person. Don't think that I don't understand it. I understand it. I understand that it was produced to mystify me, that it was produced to exclude me. Standing in front of the object she turns to the visitor.You know, if you're not one of those people who affects history—and most of us are not—then how are you supposed to enjoy looking for personal meaning in the souvenirs of that class of people who manipulate history to your exclusion? I think it takes a pretty blind state of euphoric identification to enjoy another's power to exclude you. When I visit galleries or museums, I often end up feeling angry and powerless. I find myself thinking, "Who are these people? Where did they get their money? What does all of this have to do with my experience?" I don't need to come here to be told I don't belong here. I don't need to come here to get culture. Culture is ordinary, culture is common. . . The Staff gestures around the gallery. Another visitor catches her eye. As she walks toward the visitor The Staff returns to the manner with which she began the performance.It's a beautiful show isn't it. And this. . . She walks over to one of the Plaster Surrogates.. . . is a beautiful piece . . .  Sources (by section): 1. Ester Coen. The Collection of Lydia Winston Malbin (Sotheby's: New York, 1990); Aline B. Saarinen. "Provincial Princess: Mrs. Potter Palmer" and "C'est Mon Plaisir: Isabella Stewart Gardener," The Proud Possessors (Random House, New York, 1958); from an interview with a lawyer whose "family belongs to the Parisian grande bourgeoisie," quoted in Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste, trans. Richard Nice (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1984); Guide (New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984); from interviews with Betty Parsons and Andre Emmerich, quoted in de Coppet and Jones, ed. The Art Dealers (New York, Clarkson N. Potter Inc./Publishers, 1984); "For Love Not Money," Artnews (December 1990); "Holly Solomon," Flash Art (January/February 1990) 2. Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction; Michael Harrington, The Other America (New York, Penguin, 1962); Saarinen, Provincial Princess; Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway (New York, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1925); from an interview with a Boston accountant, quoted in Robert Coles, "The Art Museum and the Pressures of Society" in Shermon E. Lee, ed., On Understanding Art Museums (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, Prentice-Hall Inc., 1975) 3. Langston Hughes, "Slave on the Block," The Ways of White Folks (New York, Vintage, 1933); from an interview with a lawyer whose "family belongs to the Parisian grande bourgeoisie," quoted in Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction; from interviews with Betty Parsons and Andre Emmerich, quoted in de Coppet and Jones, ed., The Art Dealers; "The Art of the Dealer: Keeping Pace with Arne Glimcher," New York (October 10, 1989); Christie Brown, "They Reflect Me: Ileana Sonnabend," Forbes (May 1, 1989); "Bit by the Collecting Bug," Newsweek (May 13, 1985); "I Don't Like Eggs: Janet Green, British Collector, Speaks Out on Art and the Art World," Artscribe (Summer 1990); Saarinen, "Americans in Paris: Gertrude, Leo, Michael and Sarah Stein," The Proud Possessors 4. "For Love Not Money," Artnews; Giancarlo Politi, "Peter Halley" in Flash Art (January/February 1990); "Barbara Gladstone," Flash Art; George Gilder, Wealth and Poverty (New York, Bantam Books, 1981) 5. From interviews with a Parisian nurse and a Parisian teacher, quoted in Bourdieu, Distinction; Carmen de Monteflores, Cantando Bajito/Singing Softly (San Francisco, spinsters/aunt lute, 1989) 6. From an interview with an unemployed man in Boston, quoted in Coles, "The Art Museum and the Pressures of Society;" from an interviews with a "baker's wife" and a "foreman's wife" in Grenoble, quoted in Bourdieu, Distinction; James Baldwin, "Down at the Cross," The Fire Next Time (New York, Dell, 1962) 7. From an interview with an unemployed man in Boston, quoted in Coles, The Art Museum and the Pressures of Society David Robbins, "An Interview with Allan McCollum," Arts Magazine (October 1985); Raymond Williams, "Culture is Ordinary," Resources of Hope (New York, Verso, 1989) |

|

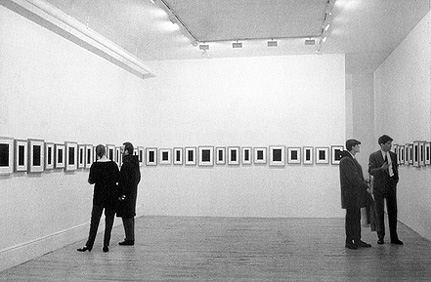

May I Help You? was first performed by Ledlie Borgerhoff, Kevin Duffy and Randolph Miles at American Fine Arts Co., New York, February 1991, in an exhibition produced in cooperation with Allan McCollum. It was also performed by Andrea Fraser at the Galerie Christian Nagel book, Art Cologne, November 1991, and at Orchard, New York, May 2005, in an exhibition that also included works by Allan McCollum.

|