|

Allan McCollum's Curiosities, Natural and Cultural

MARTHA BUSKIRK

First there was the sheer multitude of it all. Tables full of identical objects were surrounded by walls hung with varied responses to what was clearly the same environment. Depending on which of the multiple exhibition sites they experienced, viewers encountered miniature mountains, assorted concretions, multiple identical copies of one of the mineral forms known as a sand spike, or a single enlarged version of that form. And based on how much background information they brought to the experience, they may have understood the display to be the work of an artist with a longstanding interest in evocative found objects, both natural and cultural. With its many and varied components, Signs of the Imperial Valley: Sand Spikes from Mount Signal (2000-01) is an inherently hybrid project, juxtaposing objects produced by Allan McCollum with others ranging from natural specimens to landscape painting in an assembly by an artist also functioning as curator and collector.

McCollum's multipart sand-spike project participates in an increasingly expansive definition of artistic practice in the contemporary context. Yet there are also striking parallels to Charles Willson Peale's Philadelphia Museum, one of the earliest public museums in the United States, which Peale opened in 1786 and continued to develop over the next four decades. Peale's encyclopedic museum was an outgrowth of the painting gallery he had begun in conjunction with his portrait business. Like McCollum's project, it was the work of an artist with an extended job description as well as a strong interest in scientific discourse. Not only did Peale display a mix of natural history specimens and painting, but one prelude to his elaborate museum project, with its intersection of art and science, was his copies of bones. He was asked to draw the mysteriously large specimens for the benefit of a German professor unable to see them in person, and they excited such interest while on display in 1784 that Peale was encouraged to collect other objects in this vein.[1] Important, too, was the collaborative nature of the endeavor, with the varied elements of the collection contributed by many different individuals who came to share the artist's enthusiasms. Finally, there was the wonder evoked by the natural history specimens, which was linked to the museum's popular appeal.

Of course, there were a few differences too. The collection that Peale developed and eventually installed in a suite of rooms in the Philadelphia State House included an extensive display of bird specimens, organized in accordance with the Linnaean classification system. Peale employed his own innovations in taxonomy together with painted backdrops to create lifelike habitat arrangements that were shown in conjunction with insects, minerals, examples of marine life, and tribal artifacts. His idea of displaying the embalmed bodies of important men was not realized, but notables were represented in the rows of painted portraits above the array of birds, as well as by various sculpted busts and wax figures. Contributions of specimens came from many quarters, including a number from the Lewis and Clark expedition (with the natural history examples supplemented by Meriwether Lewis's donated clothing, displayed on a wax representation of the explorer), and Peale honed his expertise in dealing with the skins and sometimes living animals sent by other collectors and explorers. By far his most popular display, however, was a mastodon skeleton that he excavated himself after reading an 1801 notice about a fossil discovery on a farm in New York State. The enterprise, one of the earliest United States expeditions of this nature, yielded important evidence in relation to the question then under debate about whether species actually become extinct (with the proof summed up by Peale's son, Rembrandt: "the bones exist-the animals do not").[2]

Although McCollum has not as yet shown any particular interest in displaying embalmed statesmen or live animals, the extensive assembly of material that he presented in Signs of the Imperial Valley: Sand Spikes from Mount Signal tempts comparison to this early museum because of its synoptic approach. Even though Peale's encyclopedic collection inaugurated several centuries of museum creation, divisions by object type became the norm for the institutions that followed. McCollum is therefore operating in a changed context with respect to the number of specialized disciplines and institutions, including museums, which have grown up around the categories that Peale brought together.

McCollum also reversed Peale's terms. The spark for Peale's museum began with displays of his own paintings, which he then combined with natural specimens. McCollum's sand-spike project, by contrast, began on the natural history side of the equation, as he combined his works based on two key natural formations with paintings by local artists, and various sorts of memorabilia related to the landmark known as Mount Signal in the United States and El Cerro Centinela in Mexico. The impetus was the phenomenon of the Imperial Valley concretions, a mineral formation created by sediment deposits left by groundwater, which could obviously be categorized as a type of natural wonder. These particular, even somewhat peculiar concretions, with their decidedly phallic shapes, were specific to the long-dry Lake Cahuilia, in an area of the Imperial Valley near Mount Signal. Originally found in beds, with the majority of the spikes reportedly pointing west, the sand-spike deposits were depleted by 20th century collecting activities.

To a certain extent, however, McCollum's project also originated from a mistake: a sand spike mislabeled as a fulgurite in a Florida natural history collection prompted the artist to research both phenomena. Once he had correctly identified the object, one thing led to another, and McCollum found himself heading off to the Imperial Valley on a road trip with fellow artist Andrea Zittel, whom he invited along because her family hails from the region. Advance research pointed to the Imperial Valley College Desert Museum as a crucial destination, though that did not work out as planned when it turned out that the museum's website had described an institution that had not yet achieved a corresponding physical existence. But McCollum discovered a rewarding alternative in the Imperial Valley Historical Society Pioneers' Museum, with its wide-ranging collection devoted to the area's different populations, and even a few sand spikes erroneously categorized among the Native American artifacts, based on the misunderstanding that they were an element of some type of mortar and pestle.[3]

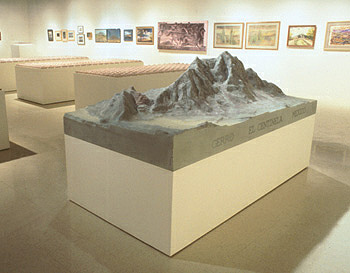

The four-year project inaugurated by these early detours is notable for an open-ended approach that wound up involving communities in both the United States and Mexico and many types of objects either produced at McCollum's instigation or created independently and brought together through his curatorial efforts. His own contributions included an array of approximately 1,000 plaster replicas of a sand spike from the Pioneers' Museum, coated in sand harvested from the base of Mount Signal; a fifteen-foot-long enlargement of that sand spike; printed information about concretions and the region; a tabletop-size model of Mount Signal; 1,000 small souvenirs of that local landmark; and a website documenting the project's many components. The sand-spike replicas were joined by many other objects, including sand-spike concretions borrowed from various collections; examples of Mount Signal imagery from historical photographs, postcards, tourist literature, signage, and corporate logos; and many painted interpretations of the landmark by area artists. These assemblies were presented in three simultaneous exhibitions during the fall of 2000 at the Pioneers' Museum, the Imperial Valley campus of San Diego State University, and in Mexicali at the Museo Universitario, Universidad Autonoma de Baja California—with the simultaneous exhibitions therefore straddling the border between the United States and Mexico in much the same way that Mount Signal sits astride this national division of the natural landscape.

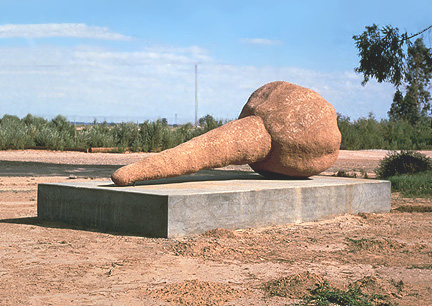

McCollum developed his own collection of sand spikes acquired from mineral shows and other sources, but it was important for him that the one he copied came from the local museum, to which it was returned. There was also some suggestion of the original disposition of the sand spikes through his multiple casts of a single specimen, arranged on a table in the same orientation. But even though it was a mineral form that brought McCollum to the Imperial Valley, he was equally interested in the community, viewing the sand spike as a potential local emblem akin to Mount Signal, but far less familiar. An important aspect of the project for McCollum was its role as a kind of communal exercise, where his pursuit of information on this regional formation would cycle back into creating local interest. Radiating out from connections established through the Pioneers' Museum, he made contact with area artists (even joining the local artists' association), one of whom, JoAnn Dutton, he commissioned to fabricate the enlarged sand spike that was eventually installed in a permanent site outside the museum.

The identical replication of the sand spikes and the mountain souvenirs presents an interesting contrast to the planned variation that has characterized many of McCollum's projects. They are part of a larger investigation of what could be broadly characterized as both cultural and natural objects—the first evident particularly in such series as the Plaster Surrogates (1982), Perfect Vehicles (1985), and Over Ten Thousand Individual Works (1987), and the latter in The Dog from Pompei (1991), Lost Objects (1991), Natural Copies from the Coal Mines of Central Utah (1994/95), and the nearly simultaneous fulgurite project THE EVENT: Petrified Lightning from Central Florida (with Supplemental Didactics) (1997). With the Lost Objects (cast dinosaur bones from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History) and Natural Copies (solid forms created naturally from negative impressions left by dinosaur tracks and found in the roofs of Utah coal mines), he continued his earlier strategy of variation through size and color. However, the casts of The Dog from Pompei are a uniform pale gray, in part because the strategy of multicolor variation seemed at odds with the powerful form of this dog, immobilized in its death struggle. The turn to undifferentiated copies also relates to another set of considerations regarding distinctions between the relative uniformity of industrial mass-production and its organic counterpart. Nature mass-produces unique objects, McCollum points out, so in a sense the strategy of his earlier work is already integral to natural specimens. His response with the fulgurites and sand spikes was to reverse course and make multiple identical copies.

The planned variation found in many of McCollum's series reads as an obvious play on the premium the art world accords to the unique. In the case of the sand spikes, however, despite the culmination of the endeavor in a three-part exhibition, this project originated and has largely remained outside art world circulation systems. The journey taken by the sand spike McCollum found in the Pioneers' Museum is telling in this respect. The sand-spike replicas were exhibited in 2000 at the Steppling Art Gallery, on San Diego State University's Imperial Valley campus, and in 2001 at the University Art Gallery at San Diego State University as part of InSITE 2000, where they were joined by the mountain model and mountain souvenirs shown initially at the Museo Universitario.[4] Rather than subsequently entering the art world economy, however, the sand-spike replicas followed the original specimen back to the Pioneers' Museum, when McCollum boxed up fifty together with related documentation to be sold as souvenirs in the museum's gift shop. In addition, the play between original specimen and souvenir replica was triangulated by the installation of the enlarged version of the same specimen at the museum. Placed outdoors adjoining the museum, it functions simultaneously as a sculpture by McCollum and as an homage to a long tradition of roadside attractions that includes both artificially enlarged objects (giant hot dogs, artichokes, and the like) as well as such natural wonders as California's everpopular drive-thru redwood.

Tourist traditions are equally relevant to the process of miniaturization that McCollum instigated for Mount Signal—which, despite its significance as a local landmark and a feature of much imagery related to the area, did not have a corresponding souvenir. Diving into this breach, McCollum used geographical data from the Mexican government and a pattern generated with rapid prototyping to create a model of the mountain in collaboration with the Museo Universitario, where it was displayed with souvenir-size plaster replicas of the mountain, produced at McCollum's behest by a workshop in Tijuana, as well as with paintings of the mountain by local Baja artists. The model also wound up in the collection of the Pioneers' Museum, donated by the Museo Universitario; unlike the sand-spike replicas, which were given to the gift shop, however, the small-scale mountain replicas remained souvenirs in appearance only.

A certain refusal of art world hierarchies has always been an aspect of McCollum's approach, evident in his early tendency to buy his art supplies in the larger retail environment of hardware stores and supermarkets or his insistence that the grouped hanging of his Plaster Surrogates might evoke domestic interiors, contemporary department stores, poster shops, or amateur exhibitions as readily as salon traditions.[5] This inclusive purview is apparent in his assembly of the views of Mount Signal/El Cerro Centinela from a multitude of sources, including the many local painters who lent works to the United States and Mexican venues. Although he acknowledges the art historical echoes of Paul Cezanne or Katsushika Hokusai in the assembly of multiple mountain views, McCollum's only requirement was that the work include a depiction of the landmark in question, and his nonexclusive curatorial approach netted a cross section of decidedly vernacular painting practices. Even Zittel got in on the act, lending a painting of the mountain by her grandmother, Opal Eshelman.

A series of inversions becomes apparent. There is the play between the giant and the miniature, with the sand-spike monument enlarged to notable proportions and the mountain where the source specimen was found turned into a small souvenir. It is the work of an artist who simultaneously relies on and highlights numerous non-art spheres of expertise. Divisions between high and low are blurred through McCollum's creation of objects that suggest roadside attractions or tourist souvenirs, shown in conjunction with groups of paintings that include manifestly amateur efforts. One of the project's specific dynamics appears in the intersection of the souvenir-like replicas produced by McCollum and the traditional medium of painting employed in many of the contributions by other creators, whose original and occasionally eccentric depictions shared exhibition space with McCollum's cast and fabricated copies. McCollum's project also drew regional attention to a regional curiosity, functioning as a kind of catalyst for activities that might help realize the potential of this hitherto underappreciated community emblem.

The relationship to the area both extends and complicates the strategies associated with an earlier generation of artists who moved outside typical exhibition venues—and in particular the interplay between site and non-site in Robert Smithson's oscillation between remotely situated Earthworks and gallery displays of uprooted material. This dichotomy has since opened onto other practices where the emphasis on a singular fixed place has given way to a more open-ended or discursive set of operations.[6] In the case of McCollum's hybrid artistic and curatorial project, which encompasses collecting and curatorial strategies along with various forms of research and collaboration, there is an equally complicated amalgam of geographic features and cultural identity reflected in his engagement with local communities via his attention to the region's natural formations. Yet the orientation is simultaneously inward and outward. Not only did McCollum acquire his Imperial Valley memorabilia on eBay (taking advantage of this efficient alternative to scouring local secondhand markets), but in addition the associated website continues to make the project available to local and international audiences alike.

Another part of the larger context is a renewed interest in the museum precursor known as the cabinet of curiosities, where natural specimens or oddities were likely to be intermixed with a range of aesthetic and mechanical wonders. McCollum's combination of natural history specimens and painted representations is an obvious point of comparison with the museum Peale established at the end of the 18th century, itself a continuation of the cabinet of curiosity model. Yet even as Peale's museum inaugurated what became over the next two centuries an institutional growth industry, with museums of all kinds appearing in all kinds of places, its encyclopedic collection was in some respects already outdated, having been instituted at a time when the Enlightenment-style generalist was being supplanted by increasingly specialized divisions by discipline. The elaboration of the museum model over the intervening centuries, including the divisions established during the 19th century between art museums and collection types focused on natural specimens or historical material, provides the backdrop for McCollum's engagement as an artist with objects and collaborations that move across these different institutions. His interest in particularly emblematic forms carries suggestive echoes of earlier collections of natural curiosities; yet those objects were often valued precisely for their inexplicable characteristics, whereas his approach highlights the ways in which the specimens he selects are deeply embedded in systems of scientific as well as cultural discourse.

By the time McCollum began researching the Imperial Valley concretions and the region where they were formed, they had long since all been harvested by collectors and souvenir hunters and were therefore to be found only in the non-site contexts of mineral shows or museums. He was therefore looking at a natural form that had already been assimilated into various collecting networks. In turn, McCollum's projects bring certain natural history specimens into the space of art—or, more specifically, their casts, in a double move that uses the umbrella of artistic authorship to complicate distinctions between original and copy as well as between nature and culture. Many of the resources McCollum has drawn upon for this project and others may be familiar to certain audiences, both professional and amateur. His particular turn on the found object, however, involves not just seeing the familiar in a new way, but bridging different nodes of specialized knowledge through the situations he highlights. A sizeable number of people have certainly been introduced to the subterranean occurrence of solidified dinosaur tracks and fulgurites via McCollum's projects, and because of a labeling problem in a Florida museum they are equally likely to learn about sand spikes. McCollum's attention to these phenomena will not erase the long-established divisions among museum types or the branches of knowledge their separation reflects; yet his engagement with certain specimens drawn from such contexts puts them back into play, highlighting the cultural significance that can accrue to such natural wonders.

Footnotes

[1.] See Edgar P. Richardson, "Charles Willson Peale and His World," and Brooke Hindle, "Charles Willson's Science and Technology," in Richardson, Hindle, and Lillian B. Miller, Charles Willson Peale and His World (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1983), 80, 110.

[2.] On the expedition, as well as on Charles Willson Peale's relationship to Enlightenment thought, see Sidney Hart and David Ward, "The Waning of an Enlightenment Ideal," in New Perspectives on Charles Willson Peale: A 250th Anniversary Celebration, ed. Lillian B. Miller and Ward (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1991), 219-35. Rembrandt Peale is quoted in Roger B. Stein, "Charles Willson Peale's Expressive Design," in New Perspectives, 192.

[3.] Descriptions of the sand-spike project are based on the documentation assembled by Allan McCollum on his website, allanmccollum.net, and on an interview with the artist by the author conducted February 23, 2008.

[4.] McCollum began working on the project in 1995. In 1999, he made a proposal to InSITE, hoping for support, and subsequently received assistance with funding and some of the fabrication logistics. The results of these efforts were exhibited first at the three regional sites in 2000 and again in 2001 in San Diego as part of InSITE 2000.

[5.] On both these points, see McCollum's comments in Robert Enright, "No Things but in Ideas: An Interview with Allan McCollum," Border Crossings (Winnipeg 20), no. 3 (fall 2001).

[6.] On this shift, see in particular Miwon Kwon, One Place after Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2002).

| |

Charles Willson Peale, The Artist in His Museum, 1822, Oil on canvas 103 3/4 x 79 7/8 inches, Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, gift of Mrs. Sarah Harrison, The Joseph Harrison, Jr. Collection

Rembrandt Peale, Working Sketch of the Mastodon, 1801, Courtesy the American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia

Archival photograph by Leo Hetzel (1877-49) of the sand spikes from Mount Signal (also known as El Cerro del Centinela), n.d., Courtesy of the Imperial Valley Historical Society Pioneers' Museum, Imperial, California

The Imperial Valley Pioneers' Museum in Imperial, California, opened in 1992. It is one of the few multi-ethnic museums in the country. The museum has fifteen different ethnic exhibitions—called galleries—on permanent display. The galleries, such as the Japanese American Gallery, represent the immigrants who came from around the world and settled in the Imperial Valley over a hundred years ago. The other ethnic galleries are: African American, Chinese, East Indian, Filipino, French, German, Greek, Korean, Lebanese, Irish, Italian, Mexican, Portuguese, and Swiss.

Signs of the Imperial Valley: Sand Spikes from Mount Signal. Installation: Gallery, San Diego State University, California, 2000

Souvenir model of Mount Signal designed by McCollum, 2000, Enamel on cast Hydro-Stone, 3' 15/16 x 5 15/16 x 3 1/8 inches

Collection of Fifty Perfect Vehicles , 1985/89, Acrylic paint on cast Hydrocal, 19 1/2 x 9 inches each, Installation in Allan McCollum , Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, the Netherlands, 1989

Over Ten Thousand Individual Works, 1987. Acrylic paint on cast Hydrocal. Between 2 x 3 and 2 x 5 inches each. Installation in Allan McCollum, Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, the Netherlands, 1989.

Over Ten Thousand Individual Works, 1987. Acrylic paint on cast Hydrocal. Between 2 x 3 and 2 x 5 inches each. Installation in Allan McCollum, Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, the Netherlands, 1989.

The Dog from Pompei, 1991. Cast glass-fiber-reinforced Hydrocal, 21 x 21 x 21 inches each. Installation in The Dog from Pompei, Galeria Weber, Alexander y Cobo, Madrid, 1992.

The Dog from Pompei, 1991. Cast glass-fiber-reinforced Hydrocal, 21 x 21 x 21 inches each. Installation in The Dog from Pompei, Galeria Weber, Alexander y Cobo, Madrid, 1992.

Opal Eshelman, Mount Signal Seen from Eshelman Ranch, 1974, Oil on canvas, 16 1/4 x 20 inches, Collection of Andrea Zittel

Fourteen-foot-long model of a sand spike fabricated in collaboration with JoAnn Dutton and InSITE 2000 in concrete, steel, and sand for permanent installation at the Imperial Valley Historical Society Pioneers' Museum, Imperial, California, 2000

Giant Artichoke, Castroville, California

Large-scale model of Mount Signal created by McCollum in collaboration wth the staff at Museo Universitario, Universidad Autonoma de Baja California, Mexicali, 2000. Built using a topographical map, polystyrene foam, plaster, and paint. 48 x 96 x 35-13/16 inches. Installation: University Gallery, San Diego State University, San Diego California.

|