Paintings help to acknowledge, validate, and construct

our inner dimensions—but they do so while maintaining

a very stable and real relation to the social world as a

whole, and the world of objects. Painting is a safe,

sanctioned, public space in which our deeply private

needs may make commerce—like a sort of flea-market

for the barter and sale of dreams, points-of-view, feelings,

etc. Therefore, whatever hidden desires we might have

regarding the relationship between our inner worlds and

the outer world might be strongly present in every act of

approaching a painting.

—Allan McCollum, letter to Nicholas Calas, 1980

—

"Maybe The Meaning Of An Artwork Is The Sum Of All

Meanings Given To It By The Sum Of Its Viewers?"

In this way, meaning might adhere to an artwork in the way

meaning becomes attached to any other common object,

perhaps in the way a pearl forms around a grain of sand,

or perhaps in the way a concretion might accrete around

a seed,or a pebble, in the sands of an ancient sea.

Is it the artist's place to participate in this community

process, in this accrual and amplification of an object's

meaning? Or is it the artist's job only to create new objects,

new meanings?

Or is it perhaps that the artist has no choice in the matter?

—Allan McCollum, introduction to

Signs of the Imperial Valley:

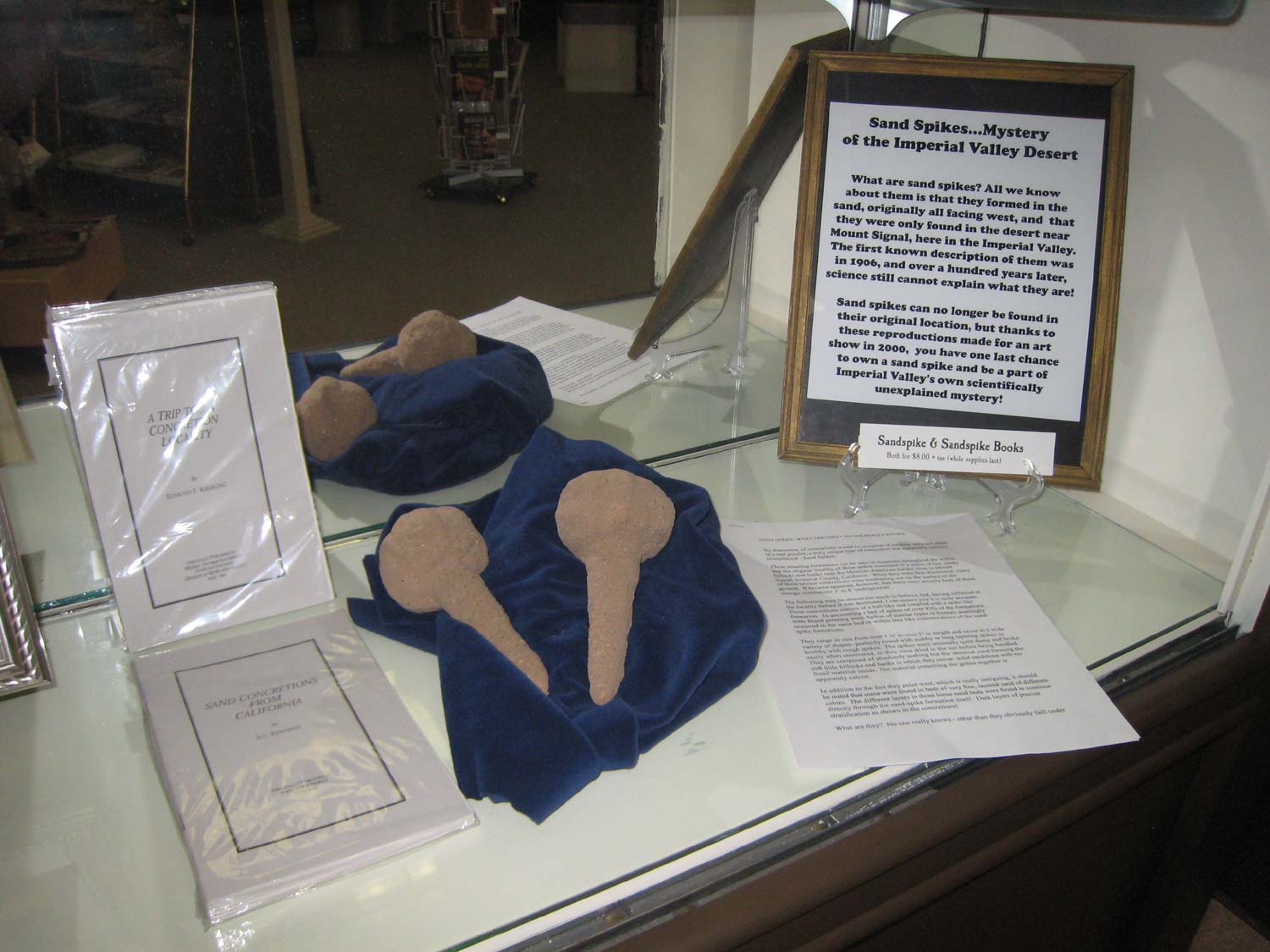

Sand Spikes from Mount Signal, 2000

—

Seizing upon [Marcel] Duchamp's strategies of Framing and of

Chance, he has extended them to encompass the ambience

and flow of consciousness, converting the Composer into

Listener absorbed in the contemplation of that Vast Found

Object, that impenetrable ritualistic spectacle, the World.

—Annette Michelson, writing about John Cage, in

"Robert Morris: An Aesthetics of Transgression," 1969

—

Mockery suggests an attitude of being against.

—Manny Farber, writing about Jean-Luc Godard,

in "The Films of Jean-Luc Godard," 1968

|

|

RHEA ANASTAS

During the late 1970s, Allan McCollum began to develop one of the primary concerns of his practice: the creation of new roles and identifications for viewers as opposed to traditional art's valuations of producer and receiver. Since then, McCollum's work has made palpable the idealizations of art's hierarchies of power and its orderings of artist and beholder within the viewing experience. In this way, his art insists on countering formalist art's transcendences of the actualities of daily life and the differences within audiences of education and class, among other social divisions.[1] McCollum staked his position in New York after a seven-year career in his native Los Angeles with two interrelated bodies of work, Surrogate Paintings, emerging in 1978, and Plaster Surrogates, following in 1982. In both series, McCollum treats the presentation of art objects as an event during which an array of cultural meanings and societal relationships can be asserted and acknowledged as politically important. The recognition of such actualities in the experience of the artwork, connecting the social and the psychic realms, calls attention to the processes of cultural reception. In this context, it is possible to locate commonalities between McCollum's work and that of Michael Asher, Daniel Buren, Andrea Fraser, Louise Lawler, and Allen Ruppersberg, among others. In McCollum's realm of perception, reception, and response, painting and other object types actually "maintain a very stable and real relation to the social world as a whole, and the world of objects," in the artist's words.[2] Within the artist's worldview, values such as approachability, abundance, and availability displace orthodox late-1960s fine-art aesthetics. Still, since that time we have hardly left these conflicts in the field of art behind, as McCollum's ongoing work reminds us.

This text examines the first of these meaningful object types to emerge thirty years ago in McCollum's work, the Surrogate Paintings and Plaster Surrogates. These two series of surrogate objects are emblematic of and foundational to the artist's continuing activity of bringing difference to the modernist medium and convention-specific artwork of 1967-69, nearing a kind of cultural anthropology of artwork type. After the Surrogate Paintings and Plaster Surrogates, McCollum's work took up a sculptural object type; a photographic object type; a drawn object type; a meaningful hand-held object type in the Over Ten Thousand Individual Works (1987) (these on a factory scale of over 10,000 count); and a group of what McCollum called "natural copy" types (fossils, traces of dinosaur footprints, fulgurites, or sand spikes). The most recent of the artist's activities has centered on The Shapes Project (2005-ongoing), whose conceptual scope encompasses multiple collaborators as well as the whole globe's population as a potential audience. It should be emphasized that all of these bodies of work have been produced and displayed in extra-artistic quantities. And yet, an analysis of the artist's thinking as a logic of production against the discrete, unique, portable artwork is not primary among the concerns of this text. Rather, my interest is McCollum's social analysis-in particular, his works' framing of cultural reception and the ways it structures and imagines new social and psychic formations and audience positions within culture.[3] The placement of the artist's The Shapes Project worksheet on the cover of this publication shows just this sort of array, organized around difference that is representative of McCollum's concerns from 1978 to now. Then and now, for McCollum, the exhibition of artwork inevitably brings into association colored, multiple interpretations. The experience of art is treated as a temporary, relational space wherein individual and group identities come forward and compete for recognition and exchange or are alienated. To borrow Craig Owens's phrasing, this kind of artwork parallels the sphere of reception aesthetics—that is, the activating of the poles of emission and reception by the literary or artistic text-and "sensitizes us to the fact that the viewer's relation to a work of art is prescribed, assigned in advance by the representational system."[4] By using the means of voice and address within the rhetorical structure of the artwork rather than enforcing a singular, social authority through art, McCollum's work performs this undoing of prescription for the viewer and communicates a sharply affecting awareness of social difference that rushes forth when we view art. As with the work of many theoretically and politically like-minded artists whose voices emerged during the late 1960s and 70s, such a position represents dissent toward the orthodox, Western, high modernist art object "whose economic and psychological value in the culture usually is concealed or, at least, not overtly stated," as described by art historian Anne Rorimer.[5]

Surrogates for Painting, 1978-1991

Writing in 1979 to the organizers of 112 Workshop, Inc., in New York, McCollum offered a concise description of his Surrogate Paintings: "I have been trying to devise a kind of artwork which can serve to represent an artwork (while at the same time being one)."[6] Each object is painted and is "about" painting, made of a support formed out of wood and museum board that has been pressed together with glue and covered by many even applications of acrylic paint.[7] Interestingly, the scale of these frame-objects is smaller than that of serious advanced art of the period, associating them with a multiplicity of things in frames that are not necessarily art. As his choice of the word "surrogate" suggests, McCollum had begun to narrow in on the cultural values attached to hierarchies of picture types. In kind and form, the Surrogates involve a singular cohering of the discrete conventional units of picture plane, "window" mat, and common picture frame through over-painting. Each surrogate of a single color is composed not by an "inside"—that figure or composition that expresses meaning—but by the painting as a "total object" which is both a surrogate for a painting and a language-like object about cultural type ("about painting"), as well as an example of advanced non-com positional painting.[8] The Plaster Surrogates take the ideas of language and convention further, being Hydro-Stone casts made from rubber molds derived from a set of twenty Surrogate Paintings and covered with multiple even coats of enamel paint. A Plaster Surrogate possesses the initial look of a Surrogate Painting, yet with a distinctly complex identity in terms of tradition, convention, and materiality. Part picture (wall-hung) and part sculptural index (though with a conspicuously painted surface), the object relates to late 1960s experiments such as Bruce Nauman's spatially expansive antiform plaster cast of the space beneath a chair that dramatically revised Minimalism's specific object.[9] Still, the portability of these frame-objects positions the Surrogate Paintings and Plaster Surrogates within the sphere of artists' critiques of exchange value since 1968 that Buren especially had articulated from the perspective of the historical line of painting. McCollum's revision was to center these problems anew within a model language of objects and their display carried through from production to reception, a language that acutely reflected the artwork's capacity for collection and domestication and for the symbolization of social roles and conditions. In this way, the Plaster Surrogates posed a counterpoint to the comparatively authentic spatial politics and positions of the works of site-specificity within the early-to-mid 1970s moment in the American context.

When Owens described the effect of an installation of the Plaster Surrogates in 1983—"551 cast 'plaster surrogates' swarmed across the gallery's walls in a continuous, undulating band"[10] —he underscored the idea that meaning in McCollum's work and the role of the viewer actually takes place at the point of presentation—that is, in the gallery, museum, or collector's home, or in an alternative space, or in reproduction.[11] Already in 1980, this idea had clarified for McCollum: "I want to install my paintings in such a way that any exhibition of my work tends to also become a symbol: a symbol of the installation of paintings."[12] The serial Surrogate Paintings were made and shown in groups; each is a measure distinct from the next through variations of dimension, color, and the proportions of plane, mat, and support. Still, the emphasis of the Surrogates, unlike most traditional painting, is on resemblance and kinship rather than stylistic or expressive singularity, and on the typologies of display that are the self-conscious language of public presentation of the objects.[13] Within the first year of exhibiting the Surrogate Paintings, McCollum began to "cluster" the objects. In an early installation during 1980 at 112 Workshop, Inc., the visitor encountered dozens of richly colored acrylic-painted Surrogates hung in a dense, elongated grouping three rows high. The exhibition's title, Collection of the Artist, made reference to the mechanisms of transfer (of ownership), exchange, and portability that underlie any public showing of an artwork. After two initial exhibitions for which McCollum had taken a formal approach to the hangings, widely spacing works in a single, even line, he abruptly eliminated the practice.[14] Subsequently, when installing the work in a single line (as might best suit a particular architecture), the artist created only the narrowest gap between each Surrogate, highlighting a logic of seriality. At the same time, McCollum was photographing the Surrogates in situ, in installations in his studio or in exhibitions, producing a body of slightly out-of-focus "reproduction-like" views that were intended only for dissemination through slide lectures, invitation cards, and posters.

McCollum had been producing and showing several kinds of task-based two-dimensional work since 1969. The idea that painting can express actualities in relation to the social world appears in an early form in his Constructed Paintings (1970-71). Works in this series, such as If Love Had Wings: A Perpetual Canon (1972) and The Gift of Tongues (1974), were the result of an unusual method of building up a whole through many small parts. To make these painting-objects, in which a single picture plane or support is absent, dozens of squares or strips of torn canvas were painted or stained and organized for assembly into rows to create a mosaiclike totality of texture, color, and pattern.[15] Not depictive of line, but constituted through edge, these works were fabricated by applying silicone adhesive caulking in black and white to each torn square's sides and then affixing them to each other. Each work's overall size, usually quite large, was determined by the total weight the individual components could bear as they were pieced together—If Love Had Wings: A Perpetual Canon measures approximately nine by twenty-seven feet.[16] The problem of the residual figuration of mark and ground had led McCollum to avoid painting on a support altogether around 1969, for it implied subordinating one part of the canvas to another and thus the continuation of a "strongly hierarchical arrangement."[17] In a letter to critic and Artforum editor Joseph Masheck in October 1978, McCollum contrasted working in this "additive way" on the Constructed Paintings with what he identified as an evolution toward the Surrogates. I have "given up this method of working," the artist stated with finality, because "the relationship these odd objects had to the discipline of painting was too ambiguous."[18]

By the early 1970s, McCollum had significant opportunities from Los Angeles spaces to show in solo and group exhibitions, including at Nicholas Wilder Gallery, the Pasadena Art Museum, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Still, in 1975, before the emergence of the Surrogate Paintings and Plaster Surrogates, McCollum relocated to the downtown New York neighborhood of SoHo at a moment of his work's increasing recognition in Los Angeles, as well as nationally, just after The Gift of Tongues had been included in the 1975 Whitney Museum of American Art biennial exhibition. Considered from the point of view of artists' activities and social circles, Los Angeles as an art center during this period offered an important alternative (anti)-schooling to which several aspects of McCollum's work emerging by the mid-1970s could be traced: a self-conscious staging of the artist's identity and voice (Edward Ruscha, Nauman, Ruppersberg) and the many works enacting "real" relationships between social worlds and painting, such as Billy Al Bengston's 1968 LACMA installation of his paintings with his friends' borrowed furniture and carpets among display walls co-designed with Frank Gehry, or Ruppersberg's 1969 Al's Cafe. This artists' context was permissive of an oppositional stance toward the orthodoxies of 1960s New York neo-avant-garde art and its formalist high/low boundaries, especially between the years 1968 and 1975. Lines of idea and exhibition continued to connect McCollum with the art community in Los Angeles, where he showed throughout the 1970s and 80s at the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art, Richard Kuhlenschmidt Gallery, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and other venues. In fact, at the same time that the artist was developing his Surrogate Paintings in New York, McCollum installed his task-based Untitled Paper Constructions (1974-75) at Claire S. Copley Gallery in Los Angeles. These were created through the assembly of shapes that McCollum designed for printing on standardized sheets of Bristol drawing paper. To produce a work, a sheet was taken from a stack of printouts and its shapes painted or limned with pencil. They were then torn out by hand and glued together, allowing for the production of dozens of images with regularized minimal compositions of varying sizes.[19] The Untitled Paper Constructions had the quality of post-studio "kitchen table" works, de-skilled in their quotidian materials and procedures and related to works by Richard Tuttle or Dorothea Rockburne of the same period. As with the Surrogates, these objects represented a two-dimensional artwork type that could be recognized as a drawing, a painting, a print, or a mixed-media work on paper. Furthermore, the Untitled Paper Constructions presaged the idea of an ongoing production of like objects, each singular example diversified from the next, continuing in an indefinite series from a mathematical permutation of a set number of elements (in this case, sixteen basic shapes in different sizes), a methodology McCollum developed over the decades with as committed and consistent a degree as the elder Sol LeWitt, with whom seriality of this type is often associated.

"Nothing but emblems...in the places of power."[20]

Exhibitions of dozens of Surrogate Paintings and, by 1983, hundreds of Plaster Surrogates, as in McCollum's first one-person show with Marian Goodman Gallery, keenly embodied the viewing process and appeared to echo the roles of audiences.[21] A line of reception for the Plaster Surrogates appearing during the mid-to-late 1980s, only after McCollum had been mounting shows of this work for at least four years, emphasized the relationship of the Plaster Surrogates to an industrial logic of production and the ways that the artist was asserting the social and institutional determinants of art. These artistic aspects were rife for connection to the societal analyses of Michel Foucault and Jean Baudrillard, among a diverse group of philosophers and thinkers who were united in the American context by the fact of being avidly read and received in the contemporary art field. In a review of McCollum's Marian Goodman Gallery show, Owens found the work "to expose the contradictions of cultural production in a market economy."[22] In his influential essay "Subversive Signs," Hal Foster layered his social analyses with ideas drawn from psychoanalytic theory, giving shape to reciprocities between maker and receiver. "For he beckons the desire to spectate and buy—the desire for spectacle, for control through consumption—only to re-present the very emptiness which the picture-fetish is supposed to fill, only to turn the ritual of mutual confirmation into a charade of (mis)recognition."[23] In this way, art theory was staging "the contradictions of cultural production in a market economy" as a particularly American post-1968 discourse of conflict between an intellectual culture and its legacies of experimental art, and a (paternalistic) capitalism largely being conjured as a post-Cold War monoculture.

In contrast, the visual and critical responses to McCollum's Plaster Surrogates by Louise Lawler—with whom McCollum has collaborated to realize several projects—and Andrea Fraser point to a related but variant line of artists' reception that interpreted both McCollum's work and this body of theory with a difference.[24] This view of McCollum's work also aligns it with feminist artists' criticism that holds the cultural value of individual achievement in a highly skeptical light. In Lawler's words, "I think art is part and parcel of a cumulative and collective enterprise, viewed as seen fit by the prevailing culture. Other work, outside work, makes up a part of this."[25]

Showing at Claire S. Copley Gallery in 1977, McCollum would have directly experienced the work by Michael Asher that emphasized the representational politics created by art galleries as social practices with its real-life form and subjects, February 8-26, 1977, Morgan Thomas at Claire Copley Gallery Inc., Claire Copley Gallery Inc. at Morgan Thomas, 918 North La Cienega Boulevard, Los Angeles, California, 2919 Santa Monica Boulevard, Santa Monica, Califomia.[26] Asher's work, simply put, had the two galleries exchange exhibition programs and locations for the duration of his eponymous project, a displacement of each onto the other in every material and habitual aspect, from the gallery owner's role and presence, to the establishment's telephone number, to each show's exhibition announcement. This exchange had the effect of highlighting the ways that exhibitions conceal their work of abstracting and transcending the actualities of the movement of artwork and the artist's identity from the contexts of idea (pre-exhibition) or studio to the contexts of public presentation and reception. Asher extended this type of critique from Buren's interrelated one of portable work and site, now pointing to the fact that the whole field of situational work was and remains structured within the art field by a language that supports market and exchange values as it demands the artist's name, invitation card, publication, and other symbolic mediums to be recognized as actual sites—really, events of representation, self-representation, and resistance—where traditional marks of authorship and gesture conventionally reside or may be destabilized.[27]

Fraser's May l Help You? (1991), one of the most singular events in this parallel sphere of reception, is a performance work conceived by Fraser to be staged within an exhibition of McCollum's Plaster Surrogates—a specially made set of the type whose "blank" centers were painted black and whose frames were articulated in an array of high-key reds and rose tones (literally lending color to the interpretative scene). For May I Help You?, actors greeted gallery visitors to American Fine Arts Co. in SoHo by voicing a scripted twenty-minute monologue structured by six sections, each of which expressed a particular position in relation to art, from knowing participation within the field, to separation and alienation from the classes who affiliate with culture. "You're branded by the objects you love. They mark you as the property of your culture, the property of your class [... ] Imagine the clothes that I'm wearing and the rest of my environment have been painted on my skin and then the whole thing is turned inside out so that it's the stuff inside-the shoes, the sofa, the dining room [... ] It's always with you. It's inside. And it's outside, at the same time, for everyone to see. It's a prison."[28] Each voluble speaker in the gallery directly addressed gallery-goers, acting with suitable interjections of arch and relieving comedy and emotional intensity. Each actor embodied the viewing and receiving processes before the Plaster Surrogates, as he or she repeated the same verbal and affective rush of desire, identification, and dis-identification before each new visitor to the gallery and before each window of the surrogate objects. Fraser's script keenly extracts the Surrogates' cultural meanings in sympathy with McCollum's ideas about the work, expressed in his exhibitions as well as in period statements and interviews (Fraser actually quoted from two of his interviews in her script). The performance made "live" such thinking of McCollum's as: "A 'surrogate painting' was meant to represent a painting in a museum, but at the same time it was meant to represent a photograph of your grandchild, or something like that. It was meant to represent a standard type of cultural object that we make, save, and value—an object in use."[29] In this superimposition of works, it is clear that Fraser and McCollum understood the social dominations that art enacts as neither hegemonic nor inevitable and, further, that these are not contained within the purview of art's institutions alone, but rather are internalized as psychic, social and sexed, private and public. Another excerpt of McCollum's writing in relation to the Surrogate Paintings relates this vividly: "Since I've been doing these paintings, I've begun to 'notice' them everywhere—through the windows of fifth-floor apartments as I walk down the street, hung unassumingly on the walls of various stage sets for television dramas, etc. I see them in fine art museums, and motel rooms, executive offices and workmen's locker rooms. I find myself constantly wondering why are they there? What are they for?"[30]

As I have argued, the two artists' performance of McCollum's Plaster Surrogates within the structure of May I Help You? reverses the naturalized modernist aesthetic work wherein"reality itself appears to speak" and enacts, through the surrogate role of the gallerist/guide/actor, a verbalization of the positions of audiences, sensitizing us to the means through which "images secure their authoritative status in our culture," as Owens so eloquently described these dynamics of modernist aesthetics in 1982.[31] But McCollum's tactics of display for the Surrogates had done this silently already, creating heightened spatial and temporal conditions for speaker and listener to exchange within a highly rhetorical scene of the address of "painting," of many painting-objects. In this sense, the Surrogate Paintings and Plaster Surrogates were crucial to McCollum's development of his exhibitions as events. Emphasizing the experiential qualities of temporary exchange, emission, and reception, his installations, collaborations, and collections of objects solicit and enhance the social behaviors ingrained within art galleries and museums, and other temporary exhibition presentations such as biennials and art fairs, as well as without.

Since 1978, the approach of the Surrogate Paintings and Plaster Surrogates had not been to continue a tradition of painting in the modernist line, but to read that tradition as a world of convention and meaning and as a total situation of authority, behavior, and feeling—in a sense, to oppose its status as canon and center (of discourse). The surrogates stood for painting and at the same time related painting in essential experiential and cultural ways to a heterogeneous world of differently valued collectibles and framed objects of everyday experience, such as the photograph of your grandchild. Connecting a serial logic resonant with modernist industrial culture with a long-standing practice of experimentation with the vernacular techniques of casting, McCollum formed the basis of an artistic language during the late 1970s that has furthered in his work with striking consistency across many variant object types and situations for display until today: the decorative-arts-associated vessel-like Perfect Vehicles (1985); to the vast groupings of Over Ten Thousand Individual Works (1987), whose hand-held forms appeal across the categories of Faberge eggs, bibelot, and ceramic figures; to the raw plaster copies of the well-known dog from the Vesuvius Museum's volcanic impression presented in a poignant installation by the dozens in The Dog from Pompei (1991); to the enlarged Pop art-inspired display of the dinosaur footprint casts, Natural Copies from the Coal Mines of Central Utah (1994/95), that the artist made from naturally formed casts of dinosaur tracks discovered by miners in the Western United States. And this is to mention only four bodies of work among the artist's past thirty years of production. An address, equal to those who are expert in or affiliated with contemporary art and to those who are not, unites McCollum's experiments within an aesthetics of reception. "I am an artist from New York," McCollum wrote to several hundred historical societies and house museums across Kansas and Missouri in 2002, "and a number of these models were made for an exhibition at a Kansas City gallery called Grand Arts. I am hoping a few of them can find use beyond the boundaries of the contemporary art world."[32] During the 2000s, viewers encountered presentations by McCollum in such disparate containers as art galleries, historical societies, science museums, and libraries, and in communicative forms via collaborations with souvenir-makers, home-based craft workers, miners, rock collectors, and neighborhood print shops. In Milan, Italy, for the joint show Sets and Situations (2008), groupings of framed black-and-white monoprints from McCollum's The Shapes Project were arranged atop Ruppersberg's brightly painted Props/Furniture (2002-ongoing). Steps, tables, and other functional furniture and pedestal-like objects that Ruppersberg had built from a 1940s set-building manual for the design and fabrication of props for theater, television, and film now carried many "McCollums," with an appeal to audiences reminiscent of Plaster Surrogate displays. Since 2001, visitors to the Imperial Valley Historical Society Pioneers' Museum in Imperial, California, have found McCollum's souvenir-like sand spikes, from a major project developed with local historians and artists based on concretions of the same shape known to collect at the base of nearby Mount Signal, paired with didactic booklets. These works of contemporary art are more or less submerged within the history-of-the-everyday of the museum's displays of Native American culture, immigrant farming, and pioneer life. Such aesthetic events and processes continue to accrue the meanings, both arch and approachable, that we have come to associate with McCollum's ritualistic and articulate art.

Footnotes

[1] By "formalist art," I mean the ideation that emerged in the American context from the mid-1950s through the late 60s and early 70s usually associated with Clement Greenberg's, Michael Fried's, and others' writings about the hegemony of painting and its meanings within a modernist line, taken as a continuous tradition.

[2] Allan McCollum, letter to Nicholas Calas, November 28 1980, unpublished document from the artist's archive, New York. McCollum replied to Calas in the context of their dialogue about Calas's inclusion of McCollum's Surrogate Paintings in the group exhibition Further Furniture (1980) at Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

[3] Writing in conjunction with a little-known exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh conceptualized the legacy of Marcel Duchamp's readymade, making the early assertion that artists including Barbara Kruger, Louise Lawler, McCollum, Sherrie Levine, and Peter Nagy "have been partially responsible for generating our awareness of these phenomena [of contemporary reception]." See Buchloh, "Ready Made, Objet Trouve, ldee Recue," in Dissent: The Issue of Modern Art in Boston, exh. cat. (Boston: Institute of Contemporary Art, 1985), 118.

[4] Reception aesthetics remains more developed in literary theory than in art history. See Craig Owens's keen analysis treating reception aesthetics in post-structuralist theory and art history, "Representation, Appropriation, and Power" (1982), in Beyond Recognition: Representation, Power, and Culture, ed. Scott Bryson, Barbara Kruger, Lynne Tillman, and Jane Weinstock (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1992), 99. As Owens pointed out, the writings of Fried and Leo Steinberg, as well as those of his peer Buchloh, can variously be associated with the field of reception aesthetics.

[5] Anne Rorimer, "Self-Referentiality and Mass-Production in the Work of Allan McCollum, 1969-1989," in Allan McCollum, exh. cat. (Eindhoven, the Netherlands. Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum; London: Serpentine Gallery; and Valencia, Spain: Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno, 1989), 8. This catalogue included a notable essay by Lynne Cooke treating McCollum's Over Ten Thousand Individual Works (1987) and the artist's thinking circa 1989.

[6] McCollum, proposal to 112 Workshop, Inc. (1979), unpublished document from the artist's archive, New York.

[7] The Surrogate Paintings were first created by McCollum with pieces of salvaged wood, but soon after were built from the constituent parts of frames (mat, frame, and back) that the artist hired a framer in New York to fabricate for him in order to utilize in the construction and painting of the objects.

[8] McCollum used the phrase "total object": "I want them to read as a total object," in his 1980 letter to Calas. In the same letter, he defined his idea of a "model" painting, what I take to be a working definition of the "surrogate" as, in his words, "something of a visual equivalent for the word, 'painting."' McCollum, letter to Calas.

[9] "McCollum's impulse is, rather, to go back to the kind of content that Nauman had built into his casts of particular spaces—which understood the very specificity of the trace itself (the "this") as a form of entropy, a congealing of the paradigm." Yve-Alain Bois and Rosalind Krauss, "A User's Guide to Entropy," October no. 78 (fall 1996): 76, excerpted in Bois and Krauss, Formless: A User's Guide (New York: Zone, 1997).

[10] Owens,"Allan McCollum: Repetition and Difference," Art in America 71, no. 8 (September 1983): 130, reprinted in Owens, Beyond Recognition, 117-21, Owens wrote this review on the occasion of McCollum's 1983 exhibition at Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

[11] In a 1977 study, McCollum depicted his Surrogate Paintings in perspective as arranged in a room such as that of a studio or gallery.

[12] McCollum, letter to Calas.

[13] McCollum wrote about developing an "objective distance" toward the discipline of painting in order to locate "the point from which all paintings, drawings, photographs, and other framed, wall-mounted artifacts can virtually begin to look alike," as if "observing this area of human activity through an anthropologically naive eye." McCollum, artist's statement (1979), unpublished document from the artist's archive, New York.

[14] McCollum installed Surrogate Paintings in this way in early solo showings of the series at Julian Pretto and Co., New York, in 1978 and at Douglas Drake Gallery, Kansas City, Missouri, in 1979, among other gallery showings.

[15] McCollum, letter to Artforum editor Joseph Masheck, October 22, 1978, unpublished document from the artist's archive. New York. Masheck had written to McCollum after seeing his work in the 1975 Whitney Biennial with several questions about his paintings and a request for images of his work.

[16] There were motifs, the grid that the pieced canvas rows established, and other symmetries upon which McCollum based the patterns such as the one that he described in The Gift of Tongues (1974) as an L-shaped "sloping drift." Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] McCollum's use of the printer shop for these works resonates with such Fluxus quotidian decisions as Daniel Spoerri's recipe-notes for materials: "Typing paper thin, for carbon copies, cut in four for personal needs From a package of 500 sheets bought for 4 francs from my news dealer." Spoerri, in Spoerri, Robert Filliou, Dieter Roth, Roland Topor, and Emmett Williams, An Anecdoted Typography of Chance (London: Atlas Press, 1995), appendix VI.

[20] Andrea Fraser, "Allan McCollum," in Investigations 1986: Allan McCollum, exh. brochure (Philadelphia: Institute of Contemporary Art, 1986), n.p. Fraser has written about McCollum's work here and in several other contexts.

[21] This was McCollum's first one-person exhibition in New York at the type of commercial gallery with which he aspired to work. The Marian Goodman Gallery show was not the emergent moment in his career, however, but rather a visible exhibition of this late 1970s work within the context of New York, where McCollum had presented Surrogate Paintings in solo and group presentations at SoHo and Tribeca alternative spaces and smaller downtown for-profit ventures since 1978. McCollum's public career had begun in 1969 and included early one-person shows at Nicholas Wilder Gallery and Claire S. Copley Gallery, both in Los Angeles. Further, it is worth noting that institutional and market conditions were taken up directly by this period's work: in the early exhibitions of Plaster Surrogates, McCollum actually priced each work differently (according to size) with the expressed desire to engage the purchaser in a process of choosing and to challenge the articulation of aesthetic judgment and subjectivity. Given how much labor this produced for the galleries selling McCollum's artworks, the Surrogates were later sold in regularized sets or collections. McCollum, e-mail to the author, August 8, 2010.

[22] Owens, "Allan McCollum: Repetition and Difference," 130.

[23] This article first appeared as Hal Foster, "Subversive Signs," Art in America 70, no. 11 (November 1982), and was reprinted later in a revised version cited here. Foster, Recodings: Art, Spectacle, Cultural Politics (Seattle: Bay Press, 1985), 104-05.

[24] Fraser, "Allan McCollum," n.p.

[25] Louise Lawler, in Martha Buskirk, "Interviews with Sherrie Levine, Louise Lawler, and Fred Wilson," October 70 (fall 1994): 106. Elsewhere, Lawler has stated the actualities of reception in this way: "The work can never be determined just by what I do or say. Its comprehension is facilitated by the work of other artists and critics and just by what's going on at the time." Lawler, in "Prominence Given, Authority Taken," interview by Douglas Crimp, Grey Room 4 (summer 2001): 75.

[26] Michael Asher, "February 8-26, 1977, Morgan Thomas at Claire Copley Gallery Inc., Claire Copley Gallery Inc. at Morgan Thomas, 918 North La Cienega Boulevard, Los Angeles, California, 2919 Santa Monica Boulevard, Santa Monica, California," in Michael Asher: Writings 1973-1983 on Works 1969-1979, ed. Buchloh (Halifax, Nova Scotia: The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design; and Los Angeles: The Museum of Contemporary Art, 1983), 154-59.

[27] See artist Mary Kelly's important critical essay "Re-Viewing Modernist Criticism" (1981), reprinted in Art after Modernism: Rethinking Representation, ed. Brian Wallis (Boston: David R. Godine; and New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1984), 87-103.

[28] Andrea Fraser, script for May I Help You? (1991), in Andrea Fraser Works: 1984 to 2003, ed. Vilmaz Dziewior, exh. cat. (Hamburg: Kunstverein in Hamburg; and Cologne: DuMont, 2003), 266. Fraser's script draws from various sources, including Pierre Bourdieu's book-length study La Distinction (1979), Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway (1925), and documentary sociological accounts of art museum audiences and social class.

[29] McCollum, interview by Thomas Lawson, in Allan McCollum (Los Angeles: A.R.T. Press, 1996), 6. This interview is based on two conversations from 1992.

[30] McCollum, letter to Calas.

[31] Owens, "Representation, Appropriation, and Power," 111.

[32] McCollum, offering letter to Kansas and Missouri historical societies, June 15, 2003, project documentation and correspondence for (2003) from the artist's archive, New York.

===================================

|

|

Photograph by Louise Lawler, Work by Allan McCollum arranged by the artist at the home of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Kaye, Rumford, New Jersey, art consultant, Jack Boulton, published in October 26 (fall 1983).

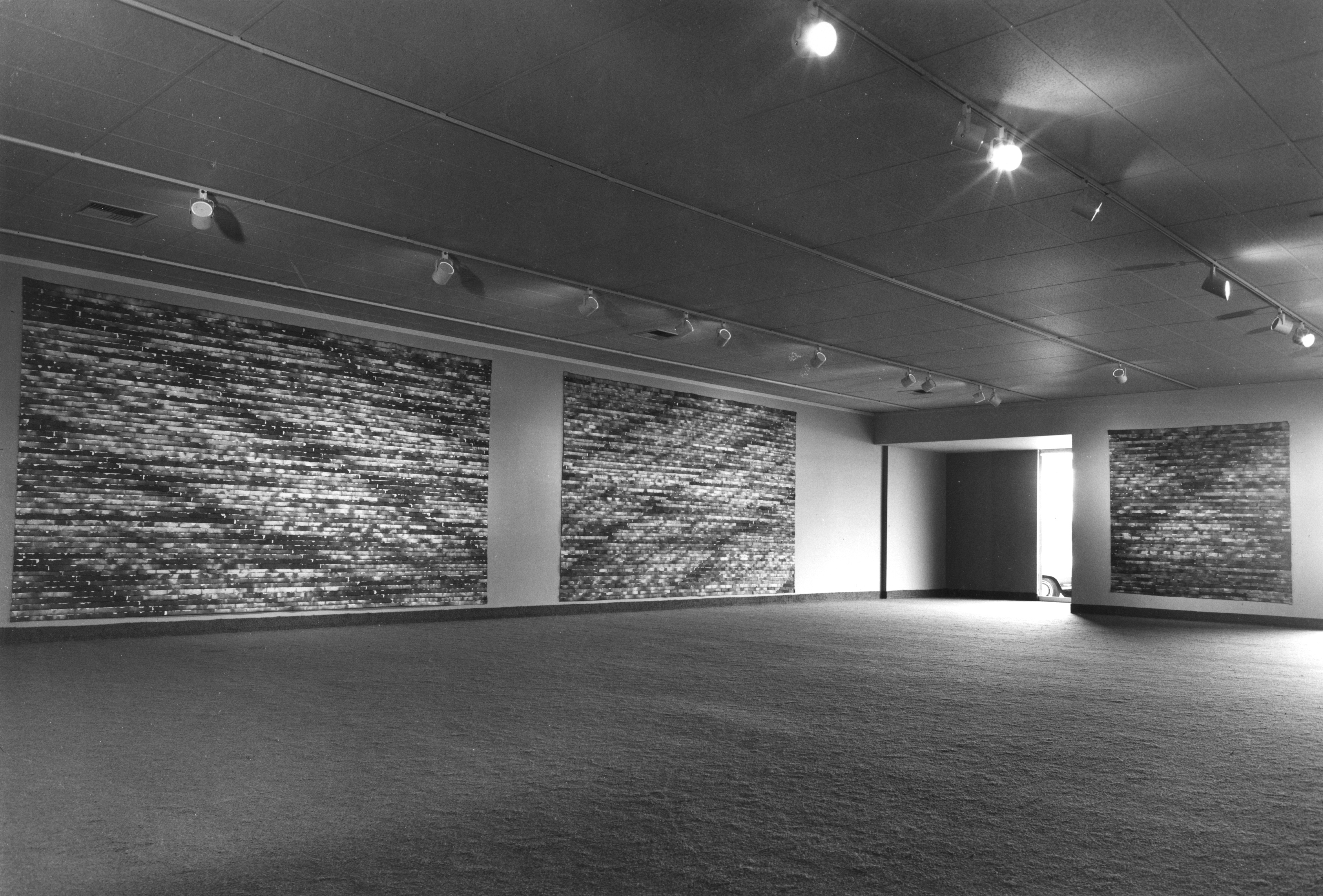

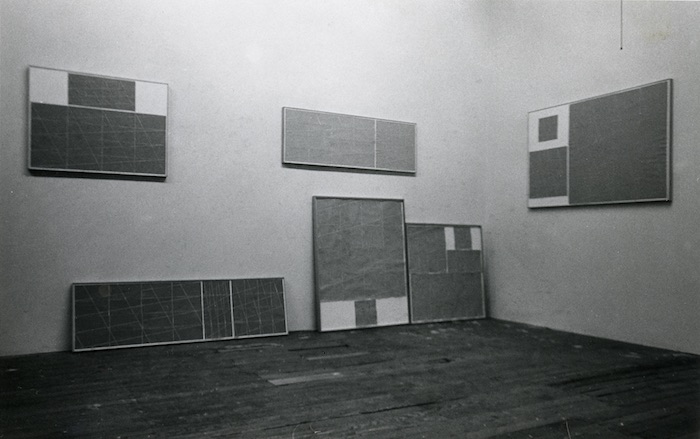

Surrogate Paintings, 1978/81. Acrylic on wood and museum board. Dimensions variable. Installation in Chase Exchange Bank lobby, New York, 1981.

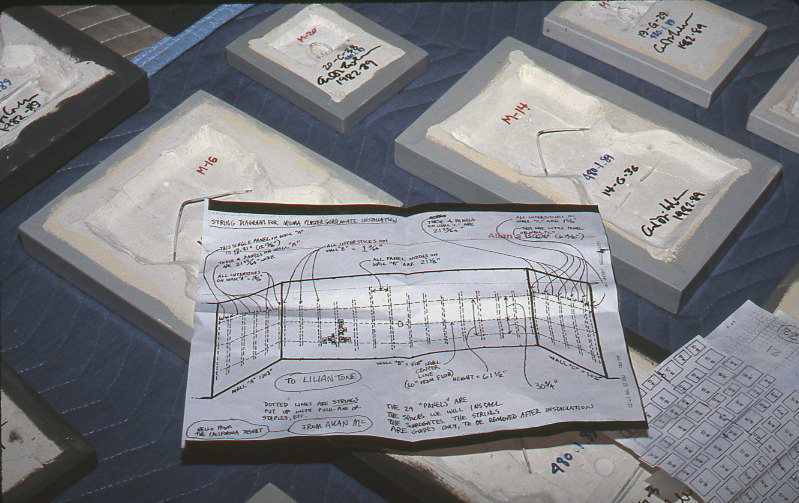

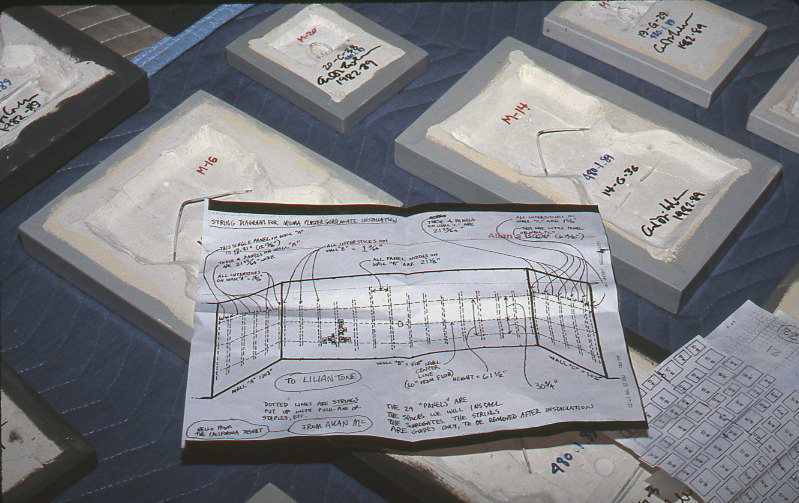

Backsides of Plaster Surrogates (1982/89) and a drawing showing the plan for their installation in The Museum as Muse: Artists Reflect, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1999.

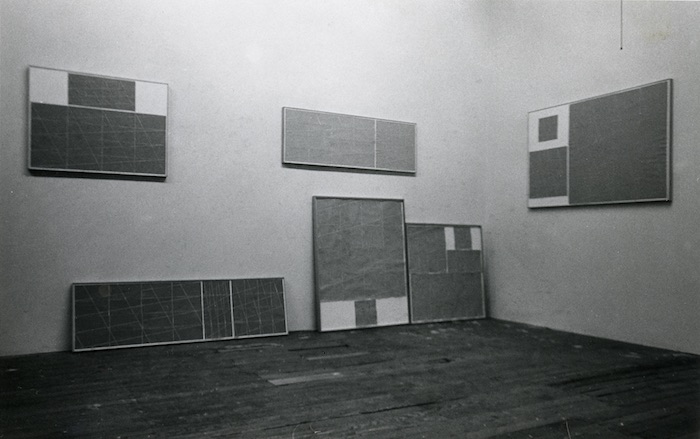

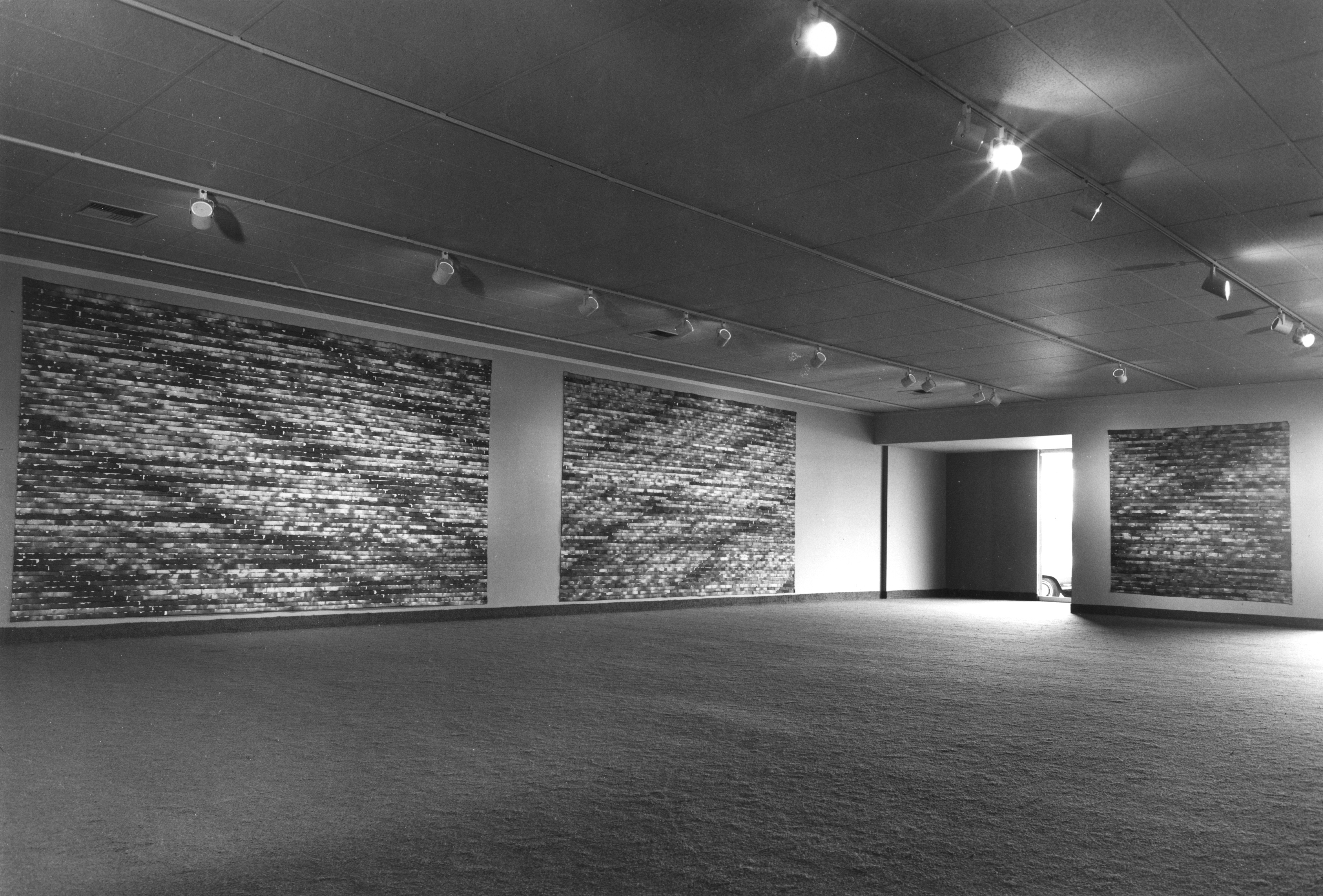

Installation of Constructed Paintings (1970-71) in Allan McCollum, Jack Glenn Gallery, Corona der Mar, California, 1971.

McCollum with Constructed Paintings, (1970-71) in his studio, Los Angeles, 1972.

Billy Al Bengston, installation at the Los Angeles County Art Museum of Art, Los Angeles, 1968. ©Museum Associates/LACMA.

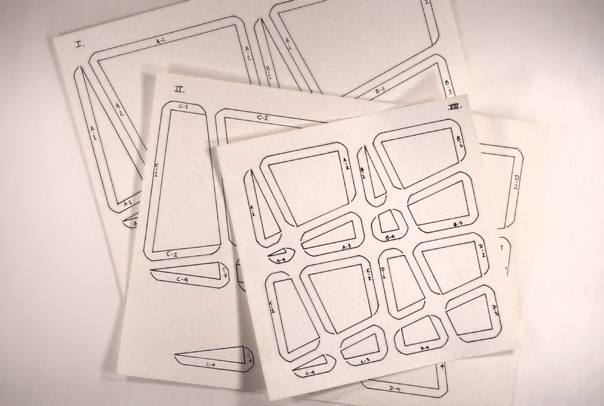

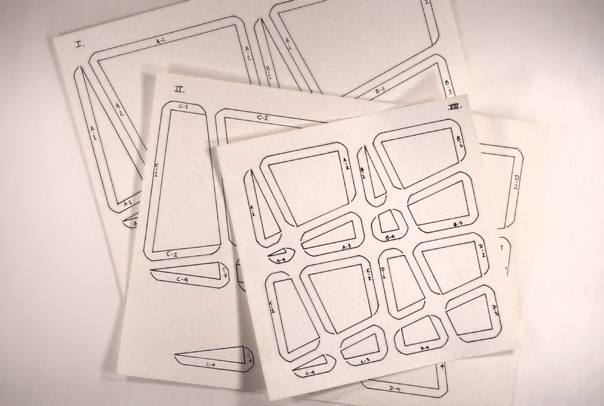

Sixteen basic shapes, printed on Bristol drawing paper, to be colored with paint, ink, or pencil, and then torn out and glued together to form Untitled Paper Constructions (1974-75).

Untitled Paper Constructions (1974-75) in process in McCollum's studio, Los Angeles, 1975

Andrea Fraser, May I Help You?, 1991. Performance produced in cooperation with McCollum, American Fine Arts Co., New York, New York, 1991.

The Dog from Pompei, 1991. Cast glass-fiber-reinforced Hydrocal, 21 x 21 x 21 inches each. Installation in The Dog from Pompei, Galeria Weber, Alexander y Cobo, Madrid, 1992.

Shapes for Hamilton, 2005/10. Over 6000 unique prints created with art students, for the residents of Hamilton Township. Image: Three generations of the DuBois family, with their Shapes, in Poolville, Hamilton Township, New York. Photo by Beth DuBois.

The Shapes Project (2005-ongoing) in progress in McCollum's studio, New York, 2005.

The Shapes Project, 2005/06. Framed digital prints, each unique, 4-1/4 x 5-1/2 inches each. Installation: Friedrich Petzel Gallery, New York, 2006.

Allan McCollum and Allen Ruppersberg, Sets and Collections, 2008. Framed digital prints, each unique, from McCollum's The Shapes Project (2005-ongoing) installed with Ruppersberg's Props/ Furniture (2002-ongoing) in Sets and Situations, Studio Guenzani, Milan, 2008.

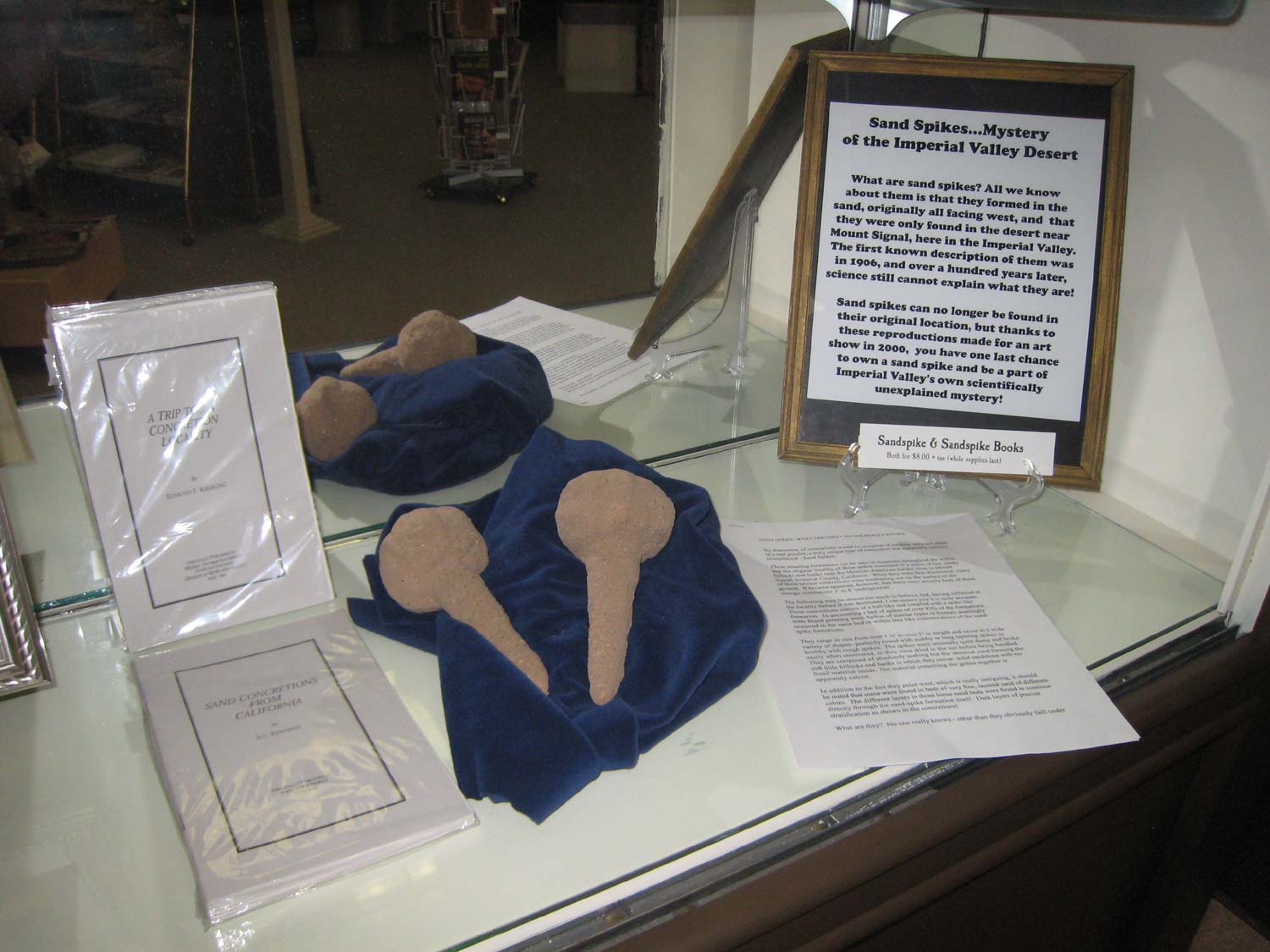

McCollum's sand spike souvenirs for sale at the Imperial Valley Historical Society Pioneers' Museum, Imperial, California, 2008.

|