Originally published in

Allan McCollum: Works since 1969

ICA Miami exhibition catalog, 2020

|

Perpetual Canon: Interview with Allan McCollum |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

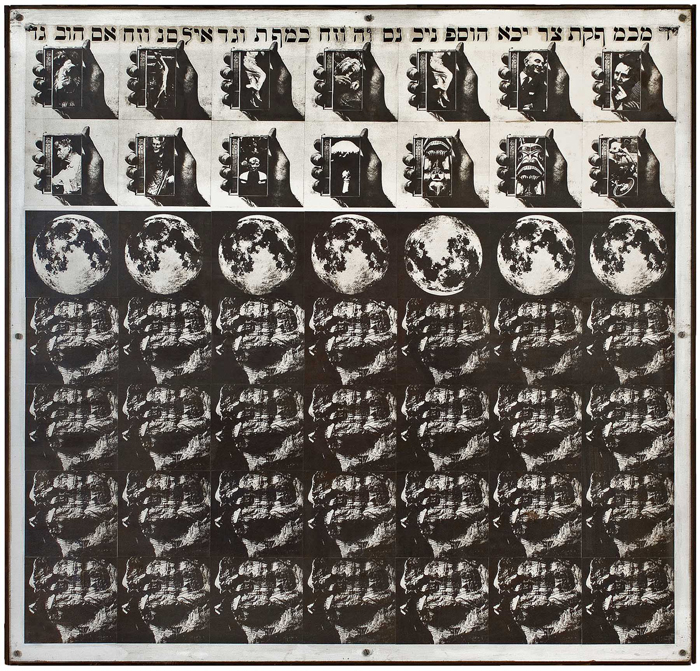

ALEX GARTENFELD Alex Gartenfeld: Allan, while you have been New York-based for over half your life, you grew up in Los Angeles. You lived there until 1975, first experienced art there, and to this day identify with the city. For me your work and your interests have deeply psychological aspects. So I wanted to begin our conversation by asking about your family. Your uncle, Jon Gnagy, starred in an educational TV show about making art. It would seem his idea of communicating art to a popular audience has stuck with you. Allan McCollum: What captured my interest about my uncle was that he would only do drawings and paintings that he could teach other people how to do. Which is very different from approaching your art as if you're the only one who has the skills to do what you're doing. AG: He wasn't the only artist in your family, by any means. AM: My father wanted to be an actor, and he did act throughout his childhood. He was in some movies. And he and my mother were in local theater all the time. AG: Did your parents move to Los Angeles to be a part of Hollywood? AM: That's why my father moved to Los Angeles. My mother moved there with her father, because he was working for the government. He was an artist, also; he could draw. But he was a cartographer for the government. He moved around the country making maps, and moved to LA in the late '30s, when my mother was still in high school. My grandmother was a piano teacher. My mother knew how to draw, she was an actor, she could sing, she could play the piano. Two different uncles were artists and their wives were artists. But they weren't contemporary, or avant-garde artists – they were more like illustrator-type artists. AG: Did you have any connection to your grandfather's cartography? It strikes me that your efforts over the last few decades to explore and understand different American regions relate to your grandfather's biography. AM: I don't remember ever seeing any of his maps, but I do remember sitting on his lap and him teaching me how to draw. My grandfather loved the exquisite corpse. I don't know if he got that from the Surrealists. He would have me draw and he'd judge what I had done, and vice versa. And, you know, sitting on his lap and learning to draw was one of the most pleasant aspects of my relationship with him. AG: Your siblings, who are musicians, also have a relationship to creativity. AM: Yes. All my siblings are musicians in one way or another. Both of my brothers are songwriters. One of my brothers had a band called the Mike McCollum Band and I used to write country songs for him, which was a hobby of mine when I was younger. One of my uncles, in addition to being an artist and a biologist, was a well-known folk singer. Sam Hinton was his name, and he could do anything. He was also a marine biologist, an illustrator, and the curator of an aquarium. AG: It sounds like, through your family, and through Hinton in particular, you encountered modes of display outside the realm of contemporary art that would influence you years later. AM: That may be true. Some of my earliest memories are of watching my parents rehearsing for a play, and thinking about the stage. AG: Music has very rarely come up in your work. AM: Well, we're considering putting a 1972 painting in the show called If Love Had Wings: A Perpetual Canon. "Perpetual canon" is a musical term for the round. If you keep repeating the painting's structure it could go on forever, an idea that is pretty much in most of my work – things that could go on forever. AG: Did you title it before or after making the work? AM: That I don't remember. Every one of those "Constructed Painting" projects could have gone on forever. There's a quote from Hans Hofmann, "Any line placed on the canvas is already the fifth." I remember reading that and thinking, "Who's to tell me what the outside edges are?" So I gave up on the idea of working on a canvas that had already told me where to end and where to begin. AG: This was your way of overcoming Hofmann. AM: No, actually, I just didn't want the edges of the canvas to tell me what to do. AG: One of the aspects of your biography you have cited as formative is that you did not have art training -- AM: I had no traditional art training. AG: Instead you studied restaurant management and went to trade school. My interpretation of these experiences will inevitably be reductive, but they appear to me as a mix of administrative and skills-based training that reflect the systems built into your art. AM: It's an unconscious thing. One of the pleasures of my childhood was being with my mother when she was cooking. She always had a full-time job and she was busy doing this and that. But when she was cooking, I could go in the kitchen and talk with her. I was very enchanted by molds – cupcake molds, or cookie cutters, or Jell-O molds. I had two siblings at the time – later on I had three – and we would often get together to decorate cookies or to make candies and wrap them. There were a lot of group tasks. It was sort of a happy time, helping my mother . . . and she would organize these events for fun! So then I went on to work in kitchens later, and I had already become interested in mold making way before my life as an artist. There was a long period in my teenage years when I wanted to be a special effects man in the film industry. The idea of industry, factory work, and film affected all artists in LA.

AG: How did you relate to artists working during that time – Claes Oldenburg with his Store, or Edward Kienholz, who had an impact on LA. AM: I didn't encounter them until I was twenty-four years old. Oldenburg was no longer living there. Kienholz I learned about when I was working as an art handler and truck driver. When I decided I wanted to be an artist, the artists I learned about and was influenced by were, say, Wallace Berman, John Cage. But I took art classes in high school and learned nothing about that kind of stuff. Later, I was amazed by artists like Roy Lichtenstein, for instance, or Vija Celmins, who were referencing reproduction. You're too young to remember, but when I was in high school, there was no such thing as a photocopy machine. AG: Right, Wallace Berman used a Verifax, an early copy machine. AM: And in those days you had to buy one of those machines for, like, 150 dollars. And they were complicated to use. You would turn on this heat and put it over a piece of paper and glass and then expose it and then take it out and lay it on another piece of paper and run it through another thing and then it would come out as an image. And then they faded after a while. I had a job at the time, working at an industrial kitchen. I was able to afford spending 150 dollars at a certain point by saving it up. AG: During the late 1960s you made a rather unique large-scale painting [Untitled (Blown up Newspaper Print), 1968], which is black and white and is the only painting I am aware of to take a photographic approach to the image. AM: Yes! The one that looks like a crumpled magazine. That work was influenced by John Cage and Robert Rauschenberg. I made a whole bunch of those paintings that I eventually threw away. I wish I had kept them. AG: I am only aware of that one. AM: My brother has one in his apartment. I would take a magazine, close my eyes, open the magazine, tear out a random page, crumple it up, push it down onto the Verifax machine, and then do the photocopy and see what it looked like. And then I would photocopy it again and again and again, until it was all just plain black and white. No grays, nothing. So it was random. Clearly John Cage was an influence on me. AG: Because you were coming to art without an art history background, how were you coming across artists like Wallace Berman? How were you meeting these people and entering the gallery circuit? AM: Well, when I went to restaurant management training I met a girl who was studying fashion design, studying how to make patterns. She had been married in the past to an artist, and because of her background, she earned money by modeling for artists sometimes. She was a model for John Altoon. Through her, I learned about certain artists. AG: You have cited as inspiration an exhibition by Billy Al Bengston at LACMA from 1968-69, where he installed not only his paintings, but also the living rooms from which they were loaned. AM: That show was very exciting to me. He collaborated with Frank Gehry on that installation. The idea of presenting paintings in the context of a "home" as opposed to a "museum" was so brilliant to me at the time. It still is now! He was interested in analyzing what it meant to be an artist, in a number of ways. One of the ways was by looking at artists "looking to be famous." Having your signature mean something. He had a chop – a pressure stamp he'd use – because he had been involved in making multiples of prints, and he'd put it right in the center of his paintings. It was like, "I'm Billy Al Bengston!," referencing fame-seeking. I don't want to say making fun of it, but some of that was there, of course. And he always used industrial materials, which was common with LA artists like DeWain Valentine, or Larry Bell, or Craig Kauffman. AG: These artists seem to have been particularly influential to you based on the industrial fabrication and forms they used from outside the art world. AM: Yeah. And they weren't the only ones. This was a significant difference, I think, between LA and what was going on in New York at that time. Billy Al would use a spray painter in order to have his work be polished and shiny. DeWain Valentine even invented a new type of resin and sold it under his name at the resin store. He was doing solid-cast, polyester methane things, made way larger than anyone else was doing. But I have to say, the LA artists I was much more influenced by would be Allen Ruppersberg, Vija Celmins, and Michael Asher. AG: I'm going to fast forward twenty years to 1991 and "Lost Objects," whose title references Marcel Duchamp's objet trouve, as well as the Freudian term "lost object," which provokes the melancholic condition. AM: I actually came up with the phrase the year my father died, so it's definitely connected to melancholy and to life and death. AG: I was thinking of your ongoing exhibition strategy of filling spaces in relationship to this notion of melancholia and mourning. And the notion of seeking to replace something that was lost, through the formal strategy of filling an architectural space. AM: Well, I don't know. When I decided to fill spaces it had to do with wanting the project to have the effect of continuing on and on and on. They only stop because we run out of space. I mean, I remember doing the "Drawings" show in 1990 [at John Weber Gallery, New York], where I filled all the walls. And then put in tables, too, and filled all the tables.

AM: At the time I was thinking about heraldry. I'd been to Europe, and in Sweden, for instance, every time you drive into a town there's a heraldic symbol on a sign near the entrance to the town. They not only have the name for the town, they have symbols from way back in their history. I was tickled. We don't have that in this country. Certain British names have heraldic symbols. There is a McCollum symbol. It triggered me to think, "What if everybody had a symbol of their own?" Rather than just saying, "I'm a Christian, so I'm represented by the cross," or, "I'm an American, so I'm represented by the flag. Or my state flower." One thing I have probably never mentioned: When I did the drawing series it was the first time I decided to come up with a technique purely based on what artists do. It was about using drawing paper and pencils and calling it "Drawings." AG: Heraldry is necessarily rather esoteric and encoded, which seems contrary to the universal relatability of many of your images. It also directly suggests a more social mode of thinking: organizing society or people through codes and signifiers. AM: Well, just before this I worked on Over Ten Thousand Individual Works [1987- ] – ultimately I made over thirty thousand unique objects – and I started thinking about how we categorize things. I remember reading at the time a book called The Naked Ape [Desmond Morris, 1967]. It was about the way humans evolved from apes and their habits. One of the things Morris pointed out was that a tribe of apes is never many more than around thirty. Humans tend to have a similarly limited amount of close friends. Then there's "super tribes" with broader identifications like, "I'm a Democrat." And we only knew there were millions or billions of people very recently, maybe three hundred years ago? In the fifteenth century nobody even knew that the world was round. They certainly didn't know that there were billions or millions and millions of people elsewhere. And so this is something we had to learn. One of the ways of dealing with that is to come up with categories. We don't know how to think in terms of large numbers – we just don't. AG: Your work, because it involves such quantity of objects, invokes perception but also the way that we as communities make things. And I am struck that with projects like Over Ten Thousand Individual Works, where the objects therein suggest sameness, comprehension, familiarity – in fact they are all different, even if these differences cannot always be readily perceived. AM: My theory is that it wasn't until the Industrial Revolution that we drifted into thinking about the unique versus the copy. There was also this feeling that things were "natural" or "cultural." Culturally produced objects were commonly made in factories; these things were copies. That influenced the way artists thought – it influenced the way everybody thinks. Making Over Ten Thousand Individual Works, when I finally finished ten thousand of them, each one hand-painted, I figured out the costs were something like five dollars each. You didn't have to be a genius to do it; anyone could. I was just using the formula "A + B, A + C, A + D" to come up with a system for producing unique works. AG: From this point forward in your work you also moved to producing works that blur the line between "naturally occurring" and "culturally produced" objects. AM: Well, the cliche was that nature produced things that were naturally unique. During my lifetime, the interest in DNA and RNA systems made it clear that nature worked by making copies. There are, like, thousands and millions of pieces of sand. I think the commonplace distinction had to do with cultural nervousness. AG: With The Dog from Pompei [1991] you start to reflect on the specific conditions of site. You found an iconic fossilized form (and a symbol of decay, even decadence) and produced it in multiples, not unlike a souvenir. In this work, the tension between the multiple and the complexities and contexts of site starts to emerge, as it would subsequently with your "regional projects." AM: For years I've been thinking, "How can a copy signify old age?" When we look at things, like a painting on the wall, it's already something old. Sometimes it's three hundred years old, if you're in a museum. But how do you create the feeling of something being old if you're just making copies? It occurred to me that fossils are copies. A fossilized dinosaur bone is not made of bone, it's made of rock. It takes sixty million years for a fossil to form, as the molecules of the bone dissolve and are replaced with stone. When I was invited to do a project at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, I discovered that the Carnegie Museum of Natural History was in the same building. I was able to work with Lynne Cooke, the curator, in order to meet the people in the natural history department. And they never visit each other, even though they're in the same building. I was able to have molds made from the Carnegie collection. In a way, you could call that regional. AG: As you just suggested, "Lost Objects" is your first project that foregrounds the roles of the people who inhabit institutions. Not incidentally, the work references modes of museum display that are distinct from those of contemporary art. AM: I had never worked with a natural history museum before, or any other kind of museum that wasn't an art museum, although I've always been interested in the "context" of an artwork. In my earliest paintings, for instance, I was thinking about the fact that a painting draws its significance in relation to other paintings, or the history of paintings, or the painting that it isn't.

AM: Well, I was out in Utah. When I was thinking about dinosaur bones for "Lost Objects" I decided to go out to Utah to look at the colors of that region. There are certain colors you associate with the Jurassic period, and you can see all those colors in the rocks and landscape of Utah. So I drove out, because I really wanted the dinosaur bones to have similar colors. I stopped in the town of Vernal to get a motel room. Vernal is a small town but it's the gateway to the national park. It was founded, in a way, by Carnegie. The woman at the motel desk asked me, "So, what are you doing here? Where are you from?" And I said, "Well, I'm from New York. I'm doing a project for the Carnegie Art Museum in Pittsburgh and I wanted to visit the Dinosaur National Monument, which was founded by Andrew Carnegie." She gave me a look and said, "Oh, we don't think much of Carnegie out here." I asked her why and she said, "He came out here before anybody knew the valley or of the dinosaur bones and he stole our heritage." I thought that was one of the weirdest things I'd heard anybody say, describing dinosaurs as their heritage. And because I'm from out West, I started thinking about that: How does a town or community define itself? In New England, you've got New Hampshire, "new" this, and "new" that. They named things after British towns and so forth. But certainly not in Utah. Instead, there were big statues of dinosaurs when you drive in the town of Vernal. This suddenly intrigued me, the way small towns identify themselves through something no one would even think of if you were from a big city. AG: How had the community represented this heritage? AM: Well, one example, I ran into a prehistoric museum in Price, Utah, where I discovered the cast dinosaur footprints. They had more than forty, which came from the roofs of coal mines. The town of Price was in Carbon County and all of the dinosaur footprints were donated to the museum by coal miners. And so, it was one of the ways they identified themselves. Once you cut them down the dinosaur footprints had little scientific value because nobody knows which kind of dinosaur they're from. So they were just local geological specimens. AG For a piece you created soon after, THE EVENT: Petrified Lightning from Central Florida (with supplemental didactics) [1997], you went to Florida, the "lightning capital of the United States," in order to think about how identity is derived from natural phenomena. The process for this piece, which involved provoking lightning in order to create geological forms, was both complex while having aspects of the hobbyist. AM: I was driving through Florida once, taking time off, and I passed a mineral museum in DeLand. They had a sign claiming they had twenty thousand mineral specimens, so of course I had to go in. In one of the displays they had what they called "fulgurites" and described as being created by lightning hitting the sand and consolidating into something. They looked like artwork. I mean, it was like an odd shape that looked like Duchamp could've made it. AG: It has a Surrealist sort of form. AM: Yeah. It's like a ball with a point coming out of it. It even has a slightly penile feel to it. When I got home I joined a geological message board and asked people to explain to me what a fulgurite was and what a sand spike was. And I learned, rather quickly, that the sand spike has nothing to do with fulgurites. It's a sand concretion that would be formed in the bottom of a river or lake. And a fulgurite is made completely differently and it has a completely different look. So I realized – and this is not uncommon – that the museum didn't know what it was. It was a sand spike but somebody had said, "Oh, I think it's a fulgurite," so they made the label that said that. AG: The museum creates contextual support that is powerful and gets disseminated. AM: Yeah. Later I was at a museum in the Imperial Valley where you do find sand spikes. And they had a sand spike that they didn't know what it was either. They thought it was a pestle, like from a mortar and pestle, created by Native Americans. I had to tell them I thought it was a sand spike from the foot of the mountain. And they changed the label. I don't know if you think about that. AG: I do think about the museum creating disinformation. [Both laugh.] AM: I was good friends with Andrea Zittel and she was good friends with Jade Dellinger, an independent curator, and he approached me once in Florida. I was on holiday, and he heard I was there so he came to see me. He asked if I would like to make a proposal for the Museum of Science and Industry in Tampa, which was looking for an artist because they were building a new building and it was a percent for art type of thing. So I said, "fulgurites!" I had already read about a fulgurite expert who was also a major lightning expert teaching at the University of Florida. So we contacted him and he let us do all of this stuff and the museum paid for the time that it would take. I think they paid him, like, ten thousand dollars or something and I got to sit around with the scientists all summer and create lightning bolts with them and so forth. I worked with this other geologist, Dan Cordier, and he was really helpful. He also loved fulgurites and he was young and we had a lot of fun together. He had been interested in fulgurites for years. So we put together a sample of different kinds of sand in this long tube and then sent a rocket up in the air so that lightning came down into the tube and made a dozen fulgurites, all from different kinds of sand. So it was an experiment. I chose which sand I liked the best. And then we did it again with just that kind of sand. AG: Is there a purpose for this lightning kind of device, which you took into your own hands, or is it just for the creation of fulgurites? AM: Well, it was a new invention. They had never made a big pipe filled with sand just to produce fulgurites. That wasn't what they were studying. They were studying the effects of lightning on metal, and air, and everything. Once we got a lightning strike to create a fulgurite I liked, in the right kind of sand, we went to a small sand souvenir workshop in central Florida and had over ten thousand copies made. Using the same kind of sand! AG: Your interest in the geological signifiers of identity continue with "Signs of the Imperial Valley: Sand Spikes from Mount Signal" [1997- 2001]. In an introduction to the project you say you focused on your questioning of your role, writing, "Is it the artist's place to participate in this community process, in this accrual and amplification of an object's meaning? Or is it the artist's job only to create new objects, new meanings?" AM: While working on the previous fulgurite project I learned that sand spikes, that particular shape of concretion, were only found at a specific place on the border of Mexico and California. And that it was, in a way, a site-based work. When I went out to take a look at Mount Signal I realized it was a symbol for almost every company, every community organization, in the local towns. On my website we show over 101 images of Mount Signal. People use its image for advertising, for their county symbols, for the local college, for postcards. People have different values, depending on where they live. That's interesting to me. When I did the show about Mount Signal, I curated a show with a number of different artists I found that had done paintings of Mount Signal. We showed them all. I made a friend, the artist Bibiana Padilla Maltos, who was from Mexicali, and she brought in a bunch of Mexican artists who had painted the mountain. Another artist friend I made in the Imperial Valley, Ginger Ryerson, had made paintings of Mount Signal many times and had a lot of friends who painted the mountain. There had never been a show of just Mount Signal paintings in the area before, so that really tickled me. AG: Not long after, you began working on "The Kansas and Missouri Topographical Model Donation Project" [2003]. This might be the most concentrated period of your regional projects, and it hinges on two significant changes in your practice. First, it marks a time when you are really looking outside of metropolitan centers as the source of meaning and production in your work. Second, rather than draw from an object in a collection, you begin to augment those collections by donating models of counties. AM: At the time I wasn't always thinking of the term "regional projects" – I don't know what I was thinking. I had a terrible experience with an art dealer I was working with. He owed me thousands of dollars from over forty-six art sales he'd made, and then he just went bankrupt. I lost my studio, and my life sort of fell apart. I got so sick of working in New York. I had a very negative feeling about the art world for a while, and I was interested in moving beyond that and thinking in other terms. AG: I would imagine this group of projects facilitated a variety of new relationships with new institutions and cultural contexts, but also impacted the economics of making and displaying your work. AM: I was interested in pleasing a different group of people aside from just art collectors and critics. AG: Intriguingly you talk about some of your interests in quantity and our ability to perceive the quantity of objects as a moral issue. The ability to make abstraction is an affective and ethical issue. And I suppose it speaks to the generosity of your efforts to engage people who are typically outside of the art world, or depicted without being activated. AM: I don't make that connection. I remember looking at Over Ten Thousand Individual Works and thinking about how, once they were made and put on display, it was impossible to imagine them all being unique. I associated this in my mind with the question, "How does a military general send thousands of people to fight in a war knowing that many of them are going to die?" And so one of the things you do is you have all the soldiers dress the same, in uniforms. It would break your heart if you had to think of them as individuals. And it is just one of the things that we as people have to deal with. AG: Well, in going outside of "cosmopolitan centers" and making work for audiences that aren't always acknowledged by fine artists, you are acknowledging audiences that are typically considered abstract or typically considered, you know, without an identity that needs to be affirmed. AM: I don't know if I'm solving anything by doing that. AG: There's no solution, right? Democracy needs to do the solving. AM: You know, I don't know how to answer that. But often there are extremely interesting artists who are interesting only to audiences where they're from. I mean, that's very common. Like, for instance, take Chicago or Texas, where there are some extremely smart, interesting artists but they're not acknowledged or represented. During the time when I was an LA artist, people outside LA paid no attention. When I moved to New York, I didn't get a show anywhere until I was here for seven years. AG: The term "populism" is a topical and toxic word; in its use today it suggests manipulating popular appeal – or rather, appeal to rural or postindustrial communities that are typically excluded from liberal appeals – in order to carry out a racist or antidemocratic agenda. Given the openness and generosity of your projects, and your appeals, I wonder how this word strikes you. AM: I've never used the word "populism." When I think of it, I think of TV or movies, or something like that. I grew up wanting to be in the film industry. Like I said, when I was in second grade I wanted to be a stunt man, and then a special effects man. When I got my first paycheck doing newspaper deliveries, the first thing I bought was a movie camera to practice trick photography. I don't think I realized I just wasn't cut out for that industry until I was twenty years old. But the idea of a Hollywood movie is that it should appeal to everyone. And if you were really clever you could make it super intelligent and appeal to really smart people and average people – all different kinds of people – all at the same time. AG: I believe "Perfect Vehicles" [1985- ] is perhaps the one group of works that draws from cinema directly. You've spoken about these large, near generic urn-like forms as being a "perfect vehicle" for a character, or for meaning. AM: Yes! That's where the term comes from, in my mind. An actor finding the perfect vehicle for their skills as an actor. AG: How did this relate to the ginger jar, the collectible that inspired the works' form? AM: I came up with the idea of the jar before I came up with the title. I was interested in the context that we see an artwork in – the gallery, often. The "Surrogate Paintings" [1978- ] and the "Plaster Surrogates" [1982- ] tried to treat the gallery like a stage set, so you would think about the context. I'm not the only artist who did that. Think of Daniel Buren or Michael Asher, for instance. Those guys really influenced that thinking for me. I was trying to come up with a sculpture version of the "Surrogate Paintings." I was thinking of a common object that people collected and kept on a shelf or on top of their fireplace. In movies, anytime they show a person's home, there's often an Asian vase somewhere. And ginger jars are objects that people collect that are not necessarily art objects to begin with, but they become like art objects over time. I tried different casts, different types of vases, and finally found one that I like because it could represent so many different things: death, the uterus, the soldier, the grandmother. It's everything – it's a symbol for a symbol. |

1.

1.

1.

1.